|

The first case, Red Lion Broadcasting v Federal Communications Commission, considers the constitutionality of a FCC rule requiring broadcasters to notify individuals who have been personally attacked in their programming, and to offer the attacked individual a chance to respond over the airwaves. The Supreme Court unanimously upheld the FCC rule, concluding that scarcity of available spectrum space justified regulating broadcasting to ensure a diversity of voices. The Court viewed broadcast licensees as trustees who take licenses with certain public interest obligations--obligations that may include complying with content-based regulations that could not be applied to other media. (The scarcity rationale is later cited by the Court in FCC v Pacifica as a basis for upholding rules prohibiting "indecent" programming.) It is interesting to contrast Red Lion with the Court's decision in Miami Herald v Tornillo, just five years later. In Tornillo, the Court unanimously strikes down a Florida law that required newspapers to print the replies of individuals who had been personally attacked in newspaper editorials. Despite the similarity of the question to that presented in Red Lion--and the fact that Red Lion was the case most discussed in briefs for both parties--the Court never even so much as mentioned Red Lion in a footnote! In Reno v ACLU (1997), the Court considers what level of scrutiny should apply to content regulation of the Internet. The Court decides the the medium deserves the highest level of First Amendment protection, noting that anyone and everyone can develop a website--the scarcity rationale of Red Lion for greater regulation therefore has no application. Applying strict scrutiny, the Court proceeds to strike down as vague and unconstitutionally overbroad the Communications Decency Act of 1996. American

Amusement

Machine

Association v Kendrick (2001) is a Seventh

Circuit case that produced an interesting opinion

(by the always interesting) Judge Richard

Posner. Posner concludes for the Court that

an Indianapolis ordinance prohibiting persons from

making available to minors graphically violent

video games violates the First Amendment.

Posner rejects the suggestion of Indianapolis that

the interactive nature of video games makes them

more potentially threatening and therefore

justifies a greater degree of content regulation

than could be applied, for example, to books or

movies.

In 2011, the

Supreme Court decided the case of Brown v Entertainment

Merchants, involving a challenge to a

California law that restricts the sale of violent

video games to minors. The Court, voting 7 to

2 to strike down the law, applied strict scrutiny

and found that the state's asserted interest in

preventing physical and psychological harm to minors

was insufficient under the First Amendment.

Justices Thomas and Breyer dissented, while Justices

Alito and Roberts concurred in the result, but would

have left the door open to more narrowly drafted

regulations. Writing for himself and four

other justices, Justice Scalia wrote that video

games deserved full First Amendment protection: "Like

the protected books, plays, and movies that preceded

them, video games communicate ideas--and even social

messages--through many familiar literary devices (such

as characters, dialogue, plot, and music) and through

features distinctive to the medium (such as the

player's interaction with the virtual world). That

suffices to confer First Amendment protection." The

Court signaled, in Packingham v North Carolina (2017),

that the First Amendment offers significant

protections against government restrictions on the use

of social media. In Packingham, the

Court considered a North Carolina law that made it a

felony for a registered sex offender to "access a

commercial social networking Web site that permits

children to become members or maintain personal web

pages." The complainant, Packingham, overjoyed

at having a traffic ticket dismissed, posted on his

Facebook page" "Praise be to GOD, WOW! Thanks Jesus!"

The posting was discovered by police and he was

prosecuted and convicted. Writing for the Court,

Justice Kennedy concluded the law violated the First

Amendment. The Court noted that even if it were

to make the questionable assumption that the law was

content-neutral, the government still had to show it

was "narrowly tailored to serve a substantial

government interest." This it could not do. In

Packingham, Justice Kennedy wrote of the

importance of social media in the modern world:

|

Red Lion Broadcasting v F. C. C. (1969) [BROADCASTING] Miami Herald v Tornillo (1974) [NEWSPAPERS] Reno v ACLU (1997) [THE INTERNET] Brown v Entertainment Merchants Ass'n (2011) [VIDEO GAMES] Packingham v North Carolina (2017) [SOCIAL MEDIA]

Billy

James Hargis: Scandals

in Eden

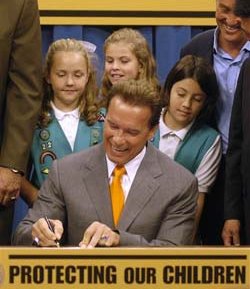

Governor

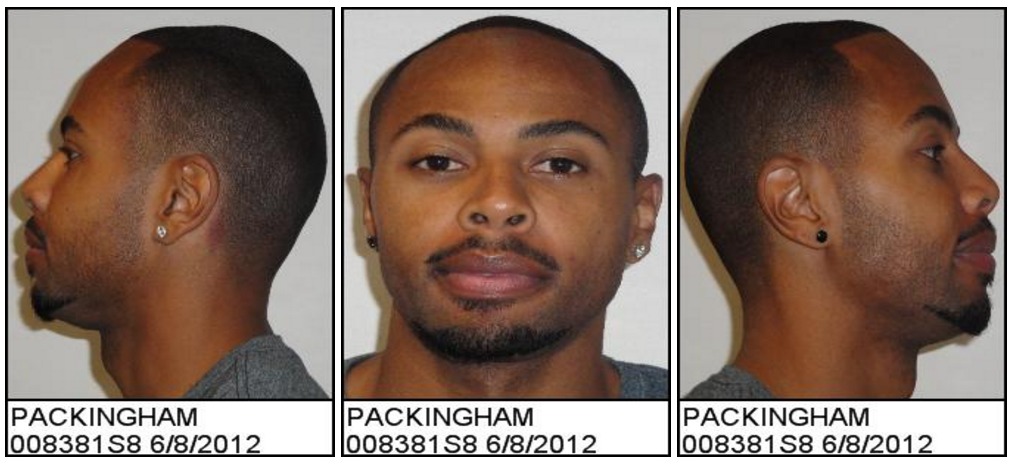

Arnold Schwarznegger signs a bill restricting the

sale of violent video games to minors.  Lester Packingham challenged a North Carolina law that prohibited registered sex offenders from accessing social media sites. Questions 2. Is there something to be said for having two very different First Amendment approaches to print and broadcast media--one given essentially free reign and one regulated more closely to provide a diversity of viewpoints? Do Red Lion and Tornillo give us "the best of both worlds"? 3. Can one argue from Red Lion that the FCC's Personal Attack Rule is not only constitutionally permissible, but constitutionally required? 4. If it were inexpensive and practicable to keep minors away from indecent and obscene material on the Internet, would Reno v ACLU have been decided differently? 5. From reading his opinion in Reno v ACLU, do you get the impression that Justice Stevens enjoys surfing the Net? 6. Do you agree with Justice Scalia's conclusion that the interactivity of video games provides no justification for greater content regulation? Do you find his distinctions between regulation of obscenity and regulation of graphically violent material convincing? 7. How would you draft a more narrowly tailored law to restrict sex offender access to social media sites, one that might survive Court scrutiny? Obviously, the problem with the North Carolina law in Packingham was not the lack of a government interest in preventing sex offenders from using social media to exploit children--the problem was the law's sweep. |

,

,