|

Introduction

The

Constitution contains no provision explicitly

declaring that the powers of the three branches of

the federal government shall be separated.

James Madison, in his original draft of what would

become the Bill of Rights, included a proposed

amendment that would make the separation of powers

explicit, but his proposal was rejected, largely

because his fellow members of Congress thought the

separation of powers principle to be implicit in

the structure of government under the

Constitution. Madison's proposed amendment,

they concluded, would be a redundancy.

The

first article of the Constitution says "ALL

legislative powers...shall be vested in a

Congress." The second article vests "the

executive power...in a President." The third

article places the "judicial power of the United

States in one Supreme Court" and "in such inferior

Courts as the Congress...may establish."

Separation

of powers serves several goals.

Separation prevents

concentration of power (seen as the root of

tyranny) and provides each branch with weapons to

fight off encroachment by the other two

branches. As James Madison argued in the

Federalist Papers (No. 51), "Ambition must be made

to counteract ambition." Clearly, our system

of separated powers is not designed to maximize

efficiency; it is designed to maximize freedom.

EXECUTIVE ENCROACHMENTS

Two very

different views of executive power have been

articulated by past presidents. One view, the

"strong president" view, favored by presidents such

as Theodore Roosevelt essentially held that

presidents may do anything not specifically

prohibited by the Constitution. The other,

"weak president" view, favored by presidents such as

Howard Taft, held that presidents may only exercise

powers specifically granted by the Constitution or

delegated to the president by Congress under one of

its enumerated powers.

Our

readings include two cases dealing with the

breadth of executive power. Youngstown

Sheet & Tube Co. v Sawyer (1952) arose

when President Harry Truman, responding to labor

unrest at the nation's steel mills during the

Korean War, seized control of the mills.

Although a six-member majority of the Court

concluded that Truman's action exceeded his

authority under the Constitution, seven justices

indicated that the power of the President is not

limited to those powers expressly granted in

Article II. Had the Congress not impliedly

or expressly disapproved of Truman's seizure of

the mills, the action would have been

upheld.

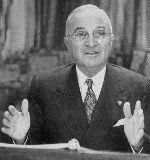

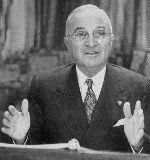

President Harry Truman announcing the seizure of

steel mills on April 8, 1952 |

Inland Steel president Clarence Randall responds

to steel mill seizure |

Dames

and More v Regan (1981) considered the

constitutionality of executive orders issued by

President Jimmy Carter directing claims by

Americans against Iran to a specially-created

tribunal. The Court, using a pragmatic

rather than literalist approach, found the

executive orders to be a constitutional exercise

of the President's Article II powers. The

Court noted that similar restrictions on claims

against foreign governments had been made at

various times by prior presidents and the Congress

had never in those incidents, or the present one,

indicated its objection to the practice.

CONGRESSIONAL ENCROACHMENTS

In INS

v Chadha (1983), the Court considered the

constitutionality of "the legislative veto," a

commonly-used practice authorized in 196 different

statutes at the time. Legislative veto

provisions authorized Congress to nullify by

resolution a disapproved-of action by an agency of

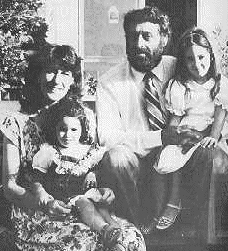

the executive branch. Chadha contended that

congressional action overturning an INS decision

suspending his deportation constituted legislative

action that failed to comply with the requirements

for legislation spelled out in Article I, Section 7

of the Constitution. The Court agreed.

Jadish Rai Chadha and family

[NY Times photo]

In Bowsher

v

Synar (1986), the Court invalidated a

provision of the Balanced Budget Act that

authorized Charles Bowsher, as Comptroller General

of the U.S., to order the impoundment of funds

appropriated for domestic or military use when he

determined the federal budget was in a deficit

situation. The Court concluded that allowing

the exercise of this executive power by the

Comptroller General, an officer--in the Court's

view--in the legislative branch, would be "in

essence, to permit a legislative veto."

Morrison

v Olson considered the constitutionality of

the "Independent Counsel" (or "special

prosecutor") provisions in the Ethics in

Government Act. The Court had considerable

difficulty in identifying in which of the three

branches of government the independent counsel

belonged. Justice Rehnquist's opinion for

the Court in Morrison took a pragmatic

view of government, upholding the independent

counsel provisions. Rehnquist noted that the

creation of the independent counsel position did

not represent an attempt by any branch to increase

its own powers at the expense of another branch,

and that the executive branch maintained

"meaningful" controls over the counsel's exercise

of his or her authority. In an angry

dissent, Justice Scalia called the Court's opinion

"a revolution in constitutional law" and said

"without separation of powers, the Bill of Rights

is worthless." Justice Scalia dissented again in Mistretta

v U. S.(1989), a decision upholding

legislation which delegated to the seven-member

United States Sentencing Commission (a commission

which included three federal judges) the power to

promulgate sentencing guidelines

In

2020, in Seila Law v CFPB, the Court found

that the structure of the Consumer Financial

Protection Board violated the Constitution's

separation of powers because it was an independent

agency headed by a single Director who exercised

substantial executive power, but who could be

removed by the President only for cause.

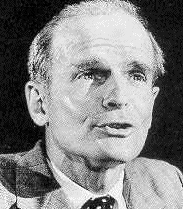

EXECUTIVE PRIVILEGE AND IMMUNITIES

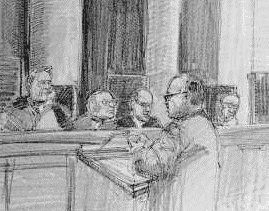

President Nixon's attorney, James

St. Clair, arguing the Watergate tapes

case before the U. S. Supreme Court

Executive

privilege, the right of the President to withhold

certain information sought by another branch of

government, was first claimed by President Jefferson

in response to a subpoena from John Marshall in the

famous treason trial of Aaron Burr. The

Supreme Court's first major pronouncement on the

issue, however, did not come until 1974 in United

States v Richard Nixon. The case

involved the refusal of President Nixon to turn over

to Watergate Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski

several hours of Oval Office tapes believed to

concern the Watergate break-in and subsequent

cover-up. Although the Court unanimously

concluded that the Constitution does indeed contain

an executive privilege, the Court said the privilege

was "presumptive" and not absolute. Balancing

the interests in the Nixon case, the Court

found the privilege not to extend to the requested

Watergate tapes.

In Clinton

v

Jones (1997), the Court rejected President

Clinton's argument that the Constitution

immunizes him from suits for money damages

for acts committed before assuming the

presidency. The case arose when Paula Jones

filed a suit alleging sexual harassment by Clinton

in an Arkansas hotel room in 1991 while Clinton

served as Governor of Arkansas.

Finally,

in Trump v Mazars, the Court considered

Congressional subpoenas demanding that the various

parties turn over financial records relating to

the activities of Donald Trump and his

businesses. The Court unanimously rejected

the president's claim of absolute privilege.

By a 7 to 2 votes, with Chief Justice Roberts

writing the opinion, the Court laid out a

four-part test courts should use in determining

whether to require that the subpoenaed

documents be turned over. The test attempts

to balance Congress's important interest in

obtaining information relevant to its

constitutional duties, and the president's

interest in not being targeted for political

reasons and thus hindered in his or her own

ability to carry out duties under Article II.

Executive

Privilege and the Treason Trial of Aaron

Burr

In 1807, Chief Justice John Marshall sat as

the trial judge in the treason trial of former

Vice President Aaron Burr. Burr, who was

accused of working with Spain to start a war in

the Southern territories and Texas (with the

suggestion that he would become the leader of a

newly-created western empire), requested that

the court subpoena certain letters of Thomas

Jefferson that might demonstrate that his arrest

was politically motivated. Marshall issued

the subpoena stating, "Courts should issue

subpoenas based on the character of the

information sought, not the character of the

person who holds it." In letters to John

Marshall, Thomas Jefferson respectfully

disagreed, but turned over the letters anyway,

thus avoiding a constitutional showdown.

To read more about the case, and to read

Jefferson's letters to Marshall click on the

following link:

|

CONGRESSIONAL IMMUNITY UNDER THE

SPEECH AND DEBATE CLAUSE

The framers sought in various ways to

guarantee the independence of each of the three

branches. The President was protected

against criminal prosecutions while in office,

answerable only in an impeachment trial with a

super-majority required to convict. Members

of the federal judiciary were given lifetime

tenure, with a guarantee that their compensation

would not be reduced. To ensure free

discussion of controversial issues in Congress,

the framers immunized members of Congress from

liability for statements made in House or Senate

debate: for their "speech or debate" they

"shall not be questioned in any other place." (Link)

Senator Proxmire of Wisconsin.

Proxmire's awarding of his "Golden Fleece" award to

Dr. Ronald Hutchinson led to a defamation

suit-- and a Supreme Court decision interpreting the

Speech and Debate Clause.

Senator Proxmire of Wisconsin.

Proxmire's awarding of his "Golden Fleece" award to

Dr. Ronald Hutchinson led to a defamation

suit-- and a Supreme Court decision interpreting the

Speech and Debate Clause.

In 1979, in Hutchinson v Proxmire,

the Court considered whether the immunity for

Senate and House debate extended beyond the

floor to cover press releases and statements

made to the media. The Court concluded

that the Speech and Debate Clause protected only

official congressional business, not statements

for public consumption.

CONGRESSIONAL ENCROACHMENT ON

JUDICIAL POWERS

Art.

III, Section. 2.

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases,

in Law and Equity, arising under this

Constitution, the Laws of the United States,

and Treaties made, or which shall be made,

under their Authority....

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors,

other public Ministers and Consuls, and

those in which a State shall be Party, the

supreme Court shall have original

Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before

mentioned, the supreme Court shall have

appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and

Fact, with

such Exceptions, and under such

Regulations as the Congress shall make.

|

In Ex Parte McCardle (1868) the Court

decided it lacked jurisdiction to consider the

habeas corpus petition of William McCardle, a

Vicksburg, Mississippi newspaper editor arrested by

military official for writing incendiary editorials

about the federal officers then in control of

Mississippi during Reconstruction. Although

McCardle made his petition under the 1867 Habeas

Corpus Act, Congress repealed the provision

authorizing McCardle's petition AFTER the Court had

heard arguments in his appeal. Although it was

obvious that Congress repealed the provision in an

attempt to specifically deprive McCardle of the

opportunity to gain release from military custody,

the Court nonetheless upheld the validity of the Act

and found itself without jurisdiction. Many

subsequent commentators, including conservative

judge Robert Bork, have criticized the Court's

decision in McCardle and have predicted that it

would not be followed today.

|

Cases

Executive

Encroachments on Legislative Powers

Youngstown Sheet

& Tube Co. v Sawyer (1952)

Dames & Moore v

Regan (1981)

Congressional

Encroachment

on Executive Powers

INS v Chadha (1983)

Bowsher v Synar (1986)

Morrison v Olson

(1988)

Seila Law v CFPB

(2020)

Judicial

Encroachment on Legislative Powers

Mistretta v U. S.

(1989)

Executive

Privilege and Immunities

United States v Nixon

(1974)

Clinton v Jones

(1997)

Trump

v Mazars (2020)

Congressional

Immunity:

Speech & Debate Clause

Hutchinson v

Proxmire (1979)

Congressional

Encroachment

on Judicial Powers

Ex Parte McCardle

(1868)

|

Separation of Powers

Provisions in the Constitution

Article I, Section. 1:

All legislative Powers herein granted shall be

vested in a Congress of the United States,

which shall consist of a Senate and House of

Representatives.

Article II, Section. 1:

The executive Power shall be vested in a

President of the United States of

America.

Article III, Section. 1:

The judicial Power of the United States shall

be vested in one supreme Court, and in such

inferior Courts as the Congress may from time

to time ordain and establish.

Article I, Section. 7:

All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate

in the House of Representatives; but the

Senate may propose or concur with Amendments

as on other Bills. Every Bill which shall have

passed the House of Representatives and the

Senate, shall, before it become a Law, be

presented to the President of the United

States: If he approve he shall sign it, but if

not he shall return it, with his Objections to

that House in which it shall have originated,

who shall enter the Objections at large on

their Journal, and proceed to reconsider it.

If after such Reconsideration two thirds of

that House shall agree to pass the Bill, it

shall be sent, together with the Objections,

to the other House, by which it shall likewise

be reconsidered, and if approved by two thirds

of that House, it shall become a Law....If any

Bill shall not be returned by the President

within ten Days (Sundays excepted) after it

shall have been presented to him, the Same

shall be a Law, in like Manner as if he had

signed it, unless the Congress by their

Adjournment prevent its Return, in which Case

it shall not be a Law.

|

Questions

1. What are some of the weapons each branch is given by

the Constitution to fend off encroachment by other

branches?

2. Which view of presidential power under the

Constitution makes the most sense to you--the "strong"

view or the "weak" view? Why? Which view has

the Court come closer to adopting?

3. How should a history of congressional inaction

in response to an assertion of presidential power be

interpreted?

4. Did the Constitution empower President Lincoln

to issue his famous Emancipation Proclamation?

5. It is not obvious that the Court has the power

to review presidential assertions of power. What

do you think about the suggestion that the Court should

refrain from reviewing these exercises of power under

"the political question" doctrine?

6. Why do you think Congress came to rely so

heavily on "legislative veto" provisions? What are

the alternatives?

7. Among the many ways of evaluating justices, one

is to measure their willingness to accept as

constitutional "pragmatic" solutions to the problems of

modern governance. On such a scale, with respect

to recent justices, might Justice White be called the

"most pragmatic" and Justice Scalia the "least

pragmatic" justice?

8. The Court seems to view the power of removal as

key to placing an official in one or another branch of

government. Why is the power of removal so

important?

9. Have special prosecutors made a positive or a

negative contribution to public life?

10. Do you accept Justice Rehnquist's argument

that the Court should be concerned when one branch seems

intent on increasing its power at the expense of other

branches, but much less so when that is not the intent

of an alleged separation of powers violation?

11. Is Justice Scalia right in suggesting, after Morrison,

we now have a "standardless judicial allocation of

powers"?

12. What do you think about the guidelines of the

U. S. Sentencing Commission? Have they served to

provide more uniform sentencing? Have they taken

too much sentencing discretion away from trial judges

and juries?

13. Could it be argued that the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure violate constitutional separation of

powers principles?

14. Could Congress delegate all of its law-making

power to a super agency and take a long vacation?

Why would such a broad delegation violate the

Constitution? How far can Congress go in

delegating its law-making powers? When are

standards for the exercise of administrative discretion

sufficient for constitutional purposes?

15. What is the best argument for recognizing

constitutional protection for claims of executive

privilege?

16. What would happen if the President were to

ignore a direct order from the Supreme Court to respond

to a legislative or judicial branch request for

information? President Nixon promised to obey "a

definitive opinion of the Supreme Court." What do

you think he meant by "definitive opinion"?

17. Should the doctrine of executive privilege

apply differently in impeachment proceedings?

18. What's the case for making the President

immune from suits for damages while in office?

|

Background on Ex

Parte McCardle

An

Example

of one of McCardle's editorials in the

Vicksburg Times (Nov. 6, 1867):

"There is not a single shade of difference

between Schofield, Sickles, Sheridan, Pope and

Ord [generals in charge of

Reconstruction]:...They are all infamous,

cowardly, and abandoned villains who, instead

of wearing shoulder straps and ruling millions

of people should have their heads shaved,

their ears cropped, their foreheads branded,

and their persons lodged in a penitentiary."

President Johnson's message in vetoing the

Repeal Act (Johnson's Veto was subsequently

overridden.):

"I cannot give my assent to a measure which

proposes to deprive any person restrained of

his or her liberty in violation of the

Constitution...the right of appeal to the

highest judicial authority known to our

government....The Supreme Court combines

judicial wisdom and impartiality to a higher

degree than any authority known to the

Constitution; any any act which may be

construed into or mistaken for an attempt to

prevent or evade its decision on a question

which affects the liberty of the citizens and

agitates the country cannon fail to be

attended with unpropitious consequences."

McCardle's

attorney on the Supreme Court decision

against his client:

"The Court stood still to be ravished and did

not even hallo while the thing was getting

done...The whole government is so rotten and

dishonest that I can only protest. It is

drunk with blood and vomits crime

incessantly."

|

19. What should the Court have done in Ex

Parte McCardle? Consider these options: (1)

Conclude that it had already determined it had

jurisdiction and ignore the repeal act; (2) Consider the

act, but hold it inapplicable because it was enacted

after oral argument had occurred; (3) Hold that the act

violated Article I, Section 9, Clause 2 in that the

suspension of habeas corpus was not required by public

safety; (4) Hold the act violated the Fifth Amendment

because it deprived McCardle of due process of law; (5)

Hold the act violates basic separation of powers

principles and that Congress cannot curtail the

jurisdiction of the Court; (6) Uphold the act and

dismiss the case for want of jurisdiction.

Paula

Jones

The

impeachment saga of President Clinton

has its origins in a sexual harassment

lawsuit brought in Arkansas in May, 1994

by Paula

Jones, a former Arkansas state

employee. In her suit, Jones

alleged that on May 8, 1991, while she

helped to staff a state-sponsored

management conference at the Excelsior

Hotel in Little Rock, a state trooper

and member of Governor Clinton's

security detail, Danny Ferguson,

approached her and told her that the

Governor would like to meet her in his

hotel suite. Minutes later, Jones,

seeing this as an opportunity to advance

her career, took the elevator to

Clinton's suite. There, according

to her disputed account, Clinton made a

series of increasingly aggressive moves,

culminating in a request for oral sex.

Jones claimed that she stood and told

the Governor, "I'm not

that kind of girl." As she left, Clinton

allegedly stopped her by the door and said,

"You're a smart girl, let's keep this

between ourselves." (There is reason

to question Jones's story, as Clinton's

security guard reported that Jones seemed

pleased when she left the hotel room--and

that anything that happened inside appeared

to be consensual.)

Lawyers for Clinton argued that the Jones

suit would distract him from the important

tasks of his office and should not be

allowed to go forward while he occupied the

White House. Clinton's immunity claim

eventually reached the United States Supreme

Court. The Court ruled unanimously in

May, 1997 against the President, and allowed

discovery in the case to proceed. As

Federal Appeals Court Judge (and Reagan

appointee) Richard A. Posner noted in An Affair of

State: The Investigation, Impeachment, and

Trial of President Clinton, the

Court's "inept," "unpragmatic," and

"backward-looking" decision in Clinton v Jones,

and an earlier

decision by the Court upholding the

constitutionality of the act authorizing the

appointment of independent counsels,

had major consequences:

"Clinton's

affair with Monica Lewinsky, an affair

intrinsically devoid of significance to

anyone except Lewinsky, would have

remained a secret from the public.

The public would not have been worse for

not knowing about it. There would

have been no impeachment inquiry, no

impeachment, no concerns about the motives

behind the President's military actions

against terrorists and rogue states in the

summer and fall of 1998, no spectacle of

the United States Senate play-acting at

adjudication. The Supreme Court's

decisions created a situation that led the

President and his defenders into the

pattern of cornered-rat behavior that

engendered a constitutional storm and that

may have embittered American politics,

weakened the Presidency, distracted the

federal government from essential

business, and undermined the rule of law."

As a result of the Supreme Court's action,

Judge Susan Weber Wright allowed discovery

to proceed in the Paula Jones lawsuit.

Judge Wright ruled that lawyers for Jones,

in order to help prove her sexual harassment

claim, could inquire into any sexual

relationships that Clinton might have with

subordinates either as Governor of

Arkansas or as President of the United

States. A critical moment in the

cascade of events that would eventually lead

to impeachment came on December 5, 1997 when

Jones's lawyers submitted a list of women

that they would like to depose.

Included on the list the name of Monica

Lewinsky.

|

|

Court's 4-Part Test for

Analyzing Appropriateness of Congressional

Subpoena for Presidential Records (Trump v

Mazars)

First, courts should

carefully assess whether the asserted

legislative purpose warrants the significant

step of involving the President and his

papers.“ ‘[O]ccasion[s] for constitutional

confrontation between the two branches’

should be avoided whenever possible.”

Congress may not rely on the President’s

information if other sources could

reasonably provide Congress the information

it needs in light of its particular

legislative objective. The President’s

unique constitutional position means that

Congress may not look to him as a “case

study” for general legislation. . . .

Second, to narrow

the scope of possible conflict between the

branches, courts should insist on a subpoena

no broader than reasonably necessary to

support Congress’s legislative objective.

The specificity of the subpoena’s request

“serves as an important safeguard against

unnecessary intrusion into the operation of

the Office of the President.”

Third, courts should

be attentive to the nature of the evidence

offered by Congress to establish that a

subpoena advances a valid legislative

purpose. The more detailed and substantial

the evidence of Congress’s legislative

purpose, the better. That is particularly

true when Congress contemplates legislation

that raises sensitive constitutional issues,

such as legislation concerning the

Presidency. In such cases, it is

“impossible” to conclude that a subpoena is

designed to advance a valid legislative

purpose unless Congress adequately

identifies its aims and explains why the

President’s information will advance its

consideration of the possible legislation.

Fourth, courts

should be careful to assess the burdens

imposed on the President by a subpoena. We

have held that burdens on the President’s

time and attention stemming from judicial

process and litigation, without more,

generally do not cross constitutional lines.

But burdens imposed by a congressional

subpoena should be carefully scrutinized,

for they stem from a rival political branch

that has an ongoing relationship with the

President and incentives to use subpoenas

for institutional advantage.

Other considerations

may be pertinent as well; one case every two

centuries does not afford enough experience

for an exhaustive list.

|

|