|

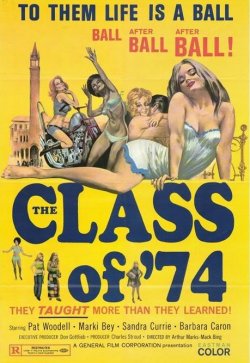

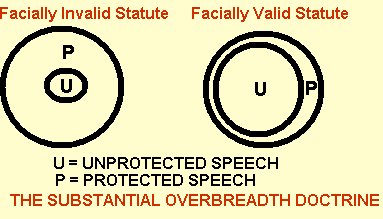

The Supreme Court has developed the doctrine of substantial overbreadth to deal with facial challenges. The doctrine recognizes that almost any law regulating speech, even when the vast majority of prohibited speech is not protected by the First Amendment, will seem to potentially reach some speech that is protected by the First Amendment. The precise reach of a statute is sometimes difficult to determine and persons who draft statutes can't be expected to anticipate every possible application of a law that must necessary be written in somewhat general terms. To strike down every law that had even one potentially impermissible application to protected speech would leave legislators powerless to deal with what might be serious threats to the public welfare or safety. In recognition of the difficulty legislators face, the Supreme Court announced in Broadrick v Oklahoma (1973) that to invalidate a law on its face it must find "the overbreadth of the statute must not only be real but substantial as well, judged in relation to the statute's plainly legitimate sweep." (Of course, a person engaging in protected speech under a statute that is overbroad, but not substantially overbroad, could succeed in an as applied challenge to the law.)  Poster for Class of '74, the film that led to Erznoznik's arrest Although the substantial overbreadth test announced in Broadrick made it more difficult to facially challenge, the Court has found a number of laws to fail even its more relaxed standard. For example, in Erznoznik v Jacksonville (1975), the Court struck down as substantially overbroad a city ordinance that made it illegal for drive-in theater operators to show movies including any form of nudity if the film could be seen from any public road or place. Richard Erznoznik faced prosecution for showing, at his outdoor theater, Class of '74, a film with more than its share of nudity. Noting that the ordinance could prohibit (absent the installation of prohibitively expensive fencing) even the showing of newsreel footage of the opening of an art exhibit, an image of a baby's buttocks, or film of bare-breasted African dancers, the Court concluded that potential application of the ordinance to protected speech was large, even given the city's legitimate concern for protecting minors from sexual images. In Board of Airport Commissioners v Jews for Jesus (1987) the Court found facially invalid a regulation adopted by the Board of Airport Commissioners for Los Angeles Airport that stated the airport was "not open for First Amendment activities by any individual." The Court chose not to decide whether the specific activity in which the challenger engaged (distributing religious literature in a terminal walkway) might have been banned under a more narrowly drafted regulation. In Virginia v Hicks (2003) the Court rejected an overbreadth challenge to a municipal housing authority trespass law. The law allowed arrest of any nonresident of a housing project who could not demonstrate "a legitimate business or social policy for being on the premises." The Court, in an opinion by Justice Scalia, indicated that if would rarely, if ever, uphold an overbreadth challenge against regulations that were not primarily directed to speech or speech-related conduct. In United States v Stevens (2010), the Court considered a federal statute that criminalized the sale or possession of "depictions of animal cruelty." After rejected the argument that depictions of animal cruelty might constitute a new category of unprotected speech, the Court considered whether the statute was overbroad in that it might reach videos depicting hunting, arguably inhumane treatment of livestock, or activities legal in some jurisdictions but not others, such as cockfighting. Chief Justice Roberts, for an 8-1 majority, wrote the opinion striking down the law as substantially overbroad. Justice Alito dissented. |

Erznoznik v Jacksonville (1975) Bd. of Airport Commissioners v Jews for Jesus (1987) Virginia v Hicks (2003) U. S. v Stevens (2010)

Terminal at LAX where Jews for Jesus sought to hand out literature  Robert Stevens, whose conviction on animal cruelty charges was overturned on First Amendment grounds. Questions 2. Won't the line between "substantial overbreadth" (unconstitutional) and just plain overbreadth (constitutional) be a fuzzy one? Should the Court require a particular ration of unconstitutional applications of a law to constitutional applications in order for an overbreadth challenge to be successful? Can you suggest any principles that would help clarify when a law should be struck down on facial grounds? 3. Should the Court adopt a bright-line rule that rejects all overbreadth challenges when the law in question is not primarily aimed at expressive activity? 4. Does the doctrine of substantial overbreadth remove the incentive that legislators might otherwise have had under a more exacting standard of judicial review to draft more precise statutes, with only a very few potentially unconstitutional applications? 5. Which of the laws challenged on vagueness grounds, the Cincinnati ordinance involved in Coates or the New York regulation of teachers involved in Keyishian, presents the stronger case for a challenge? Why? 6. If the Court were to rigorously apply the demanding standard of clarity it used in Keyishian, what other types of regulations might be vulnerable to challenge? 7. Try drafting legislation prohibiting the depiction of "animal crush videos" that could withstand judicial scrutiny under the First Amendment. |