|

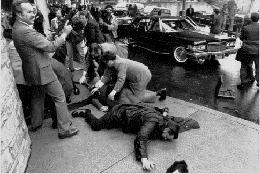

By 1967, however, the Court would note that "the major premise of Adler has been rejected." In its place was a new premise: that the government ought not to be able to do indirectly what it cannot do directly. The Court took the position that public employment cannot be conditioned on a surrender of constitutional rights. The problem for the Court then became how to balance the government's interest in maintaining an efficient public workplace against the individual employee's interest in free expression. Pickering v Board of Education considered the case of a public school teacher fired for writing a letter to a newspaper critical of the local school board. In ordering the teacher reinstated, the Court found that a public employee's statements on a matter of public concern could not be the basis for discharge unless the statement contained knowing or reckless falsehoods, or the statements were of the sort to cause a substantial interference with the ability of the employee to continue to do his job. Mt. Healthy v Doyle also involved a fired school teacher. Doyle lost his job after calling a radio station disc jockey to complain about a memo sent to school teachers concerning a new teacher dress code. Because Doyle had given the district other reasons for terminating him (such as giving "the finger" to two students), the Court remanded the case for a determination as to whether Doyle would have been fired even if he hadn't engaged in the protected expressive activity of calling the radio station. If he would have been fired anyway, the termination could stand, the Court said. Connick (1983) and McPherson (1987) both discuss the important issue of what constitutes speech "of public concern." The issue is important because, as the Court says in Connick, if speech does not relate to a matter of public concern, "absent the most unusual circumstances" the discharge will not present a First Amendment question for court review. In Connick, a 5 to 4 majority of the court concluded that speech about the internal operation of a district attorney's office is generally not of "public concern." Moreover, the Court held, distribution of a questionaire by the discharged employee raising questions about management of the office could be reasonably seen as sufficiently damaging to close working relationships to justify discharge. In Rankin, on the other hand, a 5 to 4 majority concluded that the statement "If they go for him again, I hope they get him," made immediately following news of Hinckley's attempt to assassinate President Reagan, was speech on a matter of public concern. The Court ordered the deputy constable's reinstatement, noting that the remark--made only to a fellow employee--was not likely to affect either her ability to perform her largely clerical duties in the constable's office or public confidence in the office. Branti

(1980) is one of a series of cases in which the Court has prevented

discharges

based on the political beliefs of employees. Branti was one of

six

assistant public defenders fired from a county defender's office simply

because they were Republicans and the newly appointed County Defender

was

a Democrat. The Court noted that sometimes may be permissible to

use political affiliation as a basis for hiring and discharge decisions

(for example, no one would doubt the right of the President to hire

only

Cabinet officers or speechwriters that share his or her political

affiliation),

but said that assistant county defenders did not hold the type of

decisionmaking

power that made political affiliation an appropriate

consideration.

Ten years later, in Rutan v Republican Party of Illinois (a

case

involving the staffing of Illinois prisons), the Court extended

protection

for political beliefs to initial hiring decisions, as well as decisions

relating to promotions and transfers. In 2006, in Garcetti v Ceballos, the Court considered the First Amendment claim brought by a deputy district attorney in the Los Angeles DA's office who had been transferred and denied a promotion because of his statements to supervisors criticizing the credibility of statements made in an affidavit prepared by a deputy sheriff. The Court, 5 to 4, rejected the employee's claim, holding that the First Amendment does not protect public employees for "statements made pursuant to their official duties." According to Justice Kennedy, the critical fact in the case was that "his expressions were made pursuant to his duties as a calendar deputy. That consideration--the fact that Ceballos spoke as a prosecutor fulfilling his responsibility to advise his supervisor about how to proceed with a pending case--distinguishes Ceballos' case from those in which the First Amendment provides protection against discipline.". |

Pickering

v Bd. of Education (1968)

Questions 2. If Pickering flat-out lied in his letter criticizing the School Board, would that permit the Board--consistent with the First Amendment--to use his letter as the justification for firing him? What if Pickering were an English teacher and his letter contained run-on sentences, misspellings, and various grammatical errors? What if Pickering in his letter criticized the way his fellow teachers were teaching their classes? 3. Does the First Amendment protect a teacher who is fired for refusing to raise the grade of a football star? Should it? 4. What if Pickering had promised the School Board that he wouldn't write any more critical letters to the newspaper, and then he did? Could he be fired? 5. Teacher Doyle argued with cafeteria staff over the amount of spaghetti he was served, called students "sons of bitches", and gave two students "the finger." Would anyone of those reasons have supported a decision not to rehire him? Do any of those actions constitute speech? Do they constitute speech on a matter of public concern? 6. What does Mt. Healthy v Doyle tell school districts about how they should go about firing a troublesome teacher who may have spoken out on a controversial matter of public concern--assuming that the district wants to avoid losing a lawsuit? 7. Do you agree that Myer's questionaire largely was not a matter of "public concern"? Do you agree that McPherson's statement following the Hinckley assassination attempt did address a matter of public concern? 8. If Myers had put her criticism of the operation of the district attorney's office in the form of a letter to the editor, would that have changed the Court's First Amendment analysis? 9. What if a teacher is fired for a statement on a matter that may concern the public, but that is made privately only to her supervisor? Must the speech in question be directed at the public in some way to raise serious First Amendment issues? (See Givhan v Western Line Consolidated School District (US 1979), holding that private communications are entitled to full First Amendment protection.) 10. Justice Powell, dissenting in Branti, suggests that the political patronage served important stabilizing purposes in our system of government and that its long tradition of usage suggests that it does not offend the First Amendment. Do you agree or disagree with Powell's assessment? 11. Presumably, Ceballos (the deputy district attorney disciplined for his criticism to a supervisor of the veracity of a deputy sheriff's affidavit in a pending case) might have received the protection of the First Amendment if he had gone public with the criticism (e.g., made his accusation in a letter to the editor) instead of keeping it in the office. Does this provide a perverse incentive for whistleblowers to go public with their accusations first rather than as a last resort? 12. It's clear that Ceballos addressed a matter of public concern (the integrity of criminal prosecutions). Why isn't this sufficient to win him First Amendment protection? Could the Court develop principles that adequately protect the government's interest in having flexibility in dealing with matters of employee performance and still provide incentives for employees to inform the public of government abuse or fraud? |