|

Introduction

In the Civil

Rights Cases

(1883), the Supreme Court considered the constitutionality of a civil

rights

act, enacted eight years earlier, that was remarkably broad in

scope.

The 1875 act banned racial discrimination in many types of public

accomodations,

including hotels, railroad cars, theaters, and amusement parks.

If

the 1875 act had been upheld and enforced, the United States would have

had a much happier history. Not until 1964 would such sweeping

civil

rights legislation again make it through Congress. In the Civil

Rights Cases, the Court found that neither Section 2 of the 13th

Amendment

nor Section 5 of the 14th Amendment empowered Congress to ban private

discrimination.

Writing for the Court, Justice Bradley concluded that the

discrimination

in public accomodations had "nothing to do with slavery or involuntary

servitude" and therefore fell outside of the power granted Congress in

the 13th Amendment, while Section 5 of the 14th Amendment allowed

Congress

to regulate only discrimination in which the state was an actor.

In dissent, Justice John Harlan argued that the denial of equal public

accomodations constituted a "badge of slavery" that Congress could

prohibit

under its 13th Amendment power. Moreover, Harlan argued that with

respect to discrimination in public accomodations, the discriminating

individuals

or corporations acted as "agents of the state."

Jones vs

Alfred H.

Mayer Co. (1968) arose when the developer of a surburban St. Louis

subdivision refused to sell Joseph Jones a home because he was

black.

Jones sued the developer, alleging a violation of 42 U.S.C. 1982 which

granted "all citizens of the United States...the same right as is

enjoyed

by white citizens...to purchase...real property." The Court

rejected

the developer's argument that Congress lacked the power under Section 2

of the 13th Amendment to ban private discrimination in housing.

According

to the Court in Jones, so long as Congress could rationally

conclude

that private discrimination in the housing market was "a badge of

slavery,"

the statute should be upheld.

In South

Carolina vs

Katzenbach (1966), the Court considered a challenge to provisions

of

the 1965 Voting Rights Act. South Carolina objected to provisions

that required that South Carolina (and other southern states with small

percentages of of enrolled minority voters from among those eligible to

vote) to submit to the Attorney General for "preclearance" changes in

state

voting laws. The Court found the preclearance provision to be a

constitutional

exercise of the power of Congress under Section 2 of the 15th

Amendment.

The Court saw the power of Congress as broad enough to allow creation

of

specific mechanisms for carrying out the general prohibition (the ban

on

denying the vote on account of race) of the 15th Amendment.

Another

provision of the

1965 Voting Rights Act was at issue in Katzenbach v. Morgan.

The Court considered whether the Constitution gave Congress the power

to

ban literacy tests, a device long used to deny the vote to

non-whites.

Although the Court had previously determined literacy tests to not

violate

the Equal Protection Clause, the Court nonetheless founf that the power

of Congress under Section 5 of the 14th Amendment was broad enough to

authorize

the literacy test ban. The Court seemed to see Section 5 as

giving

Congress the power to add to--but not subtract from--protections that

the

Court finds contained in the 14th Amendment. A somewhat narrower

interpretation of Morgan is that the Court will defer to

findings

of Congress that purport to establish that an applicable legal standard

(relating, e.g., to equal protection) is met--even when deferring to

those

factual findings effectively overrules Supreme Court precedent.

In Oregon

v. Mitchell

(1970), the Court rejected some of the broad language of four years

earlier

in Morgan. The Court, in finding that Congress lacked the

power to compel states to guarantee persons over the age of eighteen to

vote in state elections, indicated that Section 5 of the 14th Amendment

does not give Congress the power to enforce a broader

interpretation

of the reach of the 14th Amendment than given by the Supreme

Court.

Because the Court found the denial of the vote to 18 to 20 years olds

not

to offend the Equal Protection Clause, Congress lacked the power under

Section 5 to legislatively mandate that states allow persons in that

age

group to vote. (The extension of the right to vote to

eighteen-year

olds in state elections was subsequently accomplished by the

ratification

of the 26th Amendment in 1971). Four dissenters argued that the

Court

was bound, under Morgan, to accept Congress's more generous

interpretations

of the reach of the 14th Amendment.

In U. S. v

Guest (1966),

the U. S. attorney in Georgia brought a prosecution under Section 241

of

the 1870 Civil Rights Act against persons for intimidating and filing

false

reports against blacks who attempted to integrate public

facilities.

Those charged argued that Section 241 (which made it illegal for two or

more persons to conspire to intimidate "any citizen in the free

exercise

of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution") reached

only state actors or, if it did intend to cover private actors, it was

outside of the power of Congress. On the issue of whether

the

Constitution gave Congress the power to reach private discrimination,

six

justices suggested that it did--implying that an overruling of the Civil

Rights Cases of 1883 was appropriate.

In City of

Rome v U.

S. (1980), the Court upheld a decision of the Justice Department to

reject a proposed change in Rome, Georgia's method of electing city

commissioners.

DOJ had rejected Rome's proposed change not based on any finding that

the

change was intended to discriminate against black voters, but because

it

had the discriminatory effect of making it more difficult for

black

candidates to be elected. Even though the Court's Equal

Protection

Clause jurisprudence teaches that the Clause prohibits only purposeful

discrimination, not actions with discriminatory effects, the Court

found

Congress to have been acting within its Section 2 of the the 15th

Amendment

powers. The Court said it would defer to the judgment of Congress

that because of past "ingenious defiance" of the right of black voters,

it might be necessary to focus on discriminatory effects to uphold "the

spirit" of the 15th Amendment. Justice Rehnquist, in his dissent,

contended that the DOJ's action was not a valid exercise of Congress's

Section 2 remedial powers.

Two more

recent Supreme

Court decisions illustrate the Court's trend of reigning in

congressional

power. In 1997, in City of Boerne v Flores, the

Court

ruled that Religious Freedom Restoration Act (an Act intended to

restrore

the "compelling state interest test" for evaluating Free Exercise

Clause

claims that the Court discarded in its 1990 decision, Employment

Division

v Smith) was unconstitutional, at least as applied to state and

local

governments. The Court concluded that the Constitution, and in

particular

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, gave no power to Congress to do

more than adopt remedial measures consistent with Fourteenth Amendment

interpretations of the Court, and that Congress had instead tried to

changed

the substantive law--substituting its interpretation of the Free

Exercise

Clause for that of the Supreme Court. Finally, in U. S. vs

Morrison

(2000), invalidating the Violence Against Women Act's authorization

of private federal suits for gender-motivated assaults, the Court held

that Section 5 of the 14th Amendment--contrary to the suggestion of six

justices in Guest--gave Congress no power to reach private

discrimination.

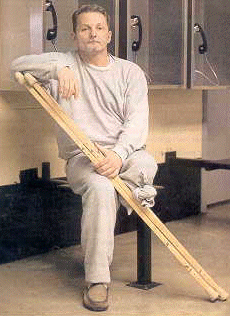

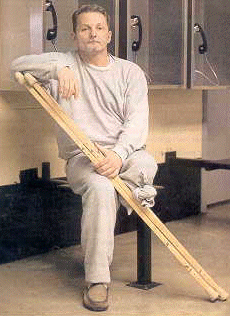

George Lane, the plaintiff who sued Tennessee for

violating the ADA

(photo: ABA Journal)

Tennessee v. Lane (2004) reflects,

primarily, the concerns of one justice (O'Connor) about going too far

in the direction of restricting Congress's ability to deal with action

(and inaction) by states that might be preventing citizens from fully

exercising rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. Justice

O'Connor provided the deciding fifth vote to uphold, as a valid

exercise of Congress's powers under Section 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment, provisions in Article II of the Americans with Disabilities

Act that allowed citizens to sue states that failed to provide adequate

access for disabled citizens to courtrooms. The Court determined

that denials of the right of access to state courts triggered strict

scrutiny under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

(incorporation of the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth amendment,

right of defendant to be present at his trial, right for a "meaningful

opportunity to be heard," incorporation of the press's First Amendment

right to report trial proceedings) and therefore the provisions of the

ADA constituted "reasonable prophylactic remedial legislation" within

the power of Congress to adopt. In an interesting dissent,

Justice Scalia announced that he regretted ever suggesting that the

Congress had power under Section 5 to enact prophylactic legislation,

and henceforward he would only recognize--except, for stare decisis

reasons, with respect to racial discrimination--the power of Congress

to "enforce" the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Cases Defining the power to

enforce

the protections

of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments:

Jones

vs Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968)

South

Carolina vs Katzenbach (1966)

Katzenbach

vs Morgan (1966)

Oregon

vs Mitchell (1970)

U.

S. vs Guest (1966)

Rome

vs U. S. (1980)

City

of Boerne vs Flores (1997)

U.

S. vs Morrison (2000)

Tennessee v Lane

(2004)

|

|

Constitutional Grants of Powers

to Congress under

the Civil War Amendments

AMENDMENT XIII

Passed by

Congress January 31,

1865. Ratified December 6, 1865.

Section 1.

Neither slavery nor involuntary

servitude,

except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly

convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject

to

their jurisdiction.

Section

2.

Congress

shall have

power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

AMENDMENT XIV

Passed by

Congress June 13, 1866.

Ratified July 9, 1868.

Section 1.

All persons born or naturalized

in the

United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of

the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall

make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or

immunities

of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person

of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to

any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws.

Section 2-4

[omitted].

Section

5.

The

Congress shall

have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions

of

this article.

AMENDMENT XV

Passed by

Congress February 26,

1869. Ratified February 3, 1870.

Section 1.

The right of citizens of the

United States

to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any

State on account of race, color, or previous condition of

servitude.

Section

2.

The

Congress shall

have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

|

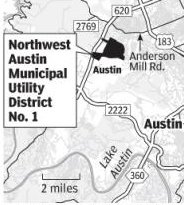

Northwest Austin Municipal Utility

District v Mukasey (2009)

In January 2009, the

Supreme Court granted cert in a case testing the power of Congress to

extend the "preclearance" provisions (Section 5) of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965 for an additional 25 years. The provision in question

requires that federal permission be given before election procedure

changes can go into effect in jurisdictions with a previous history of

disenfranchising minority voters. The appeal argues that the

extension cannot be applied to the Texas sewer district in question

given "the utter absence of any present-day pattern of unconstitutional

voting-rights deprivations of the type Section 5 was originally

designed to address." Supporters of the extension argue that

Congress has the power to enact laws to deter voting rights violations,

and that the Texas district is "trying to blame Section 5 for its own

success."

|

Questions

1. What would seem to be a better basis for upholding the

public accomodations

provisions of civil rights laws, the Commerce Clause or the enforcement

powers granted to Congress in the Civil War amendments?

2. It has been suggested that holding private discrimination

outside the reach of the federal government serves several values: it

enhances

individual liberty (the choice of individuals not to associate

with

other individuals is respected), it reinforces pluralism and the

principle

of federalism. What do you think of these arguments?

3. The 13th Amendment is unique in that by its own words it

applies

to private individuals as well as government. How far does Section 2 of

the 13th Amendment go in allowing Congress to reach forms of private

discrimination?

If discrimination in housing can be "a badge of slavery," might also

discrimination

in the membership policies of a private club? How does one

determine

what is or is not a "badge of slavery" reachable by Section 2 of the

13th

Amendment?

4. In South Carolina v Katzenbach the Court says it will

determine only whether Congress has chosen a "rational" means of

enforcing

its 15th Amendment powers. Do you agree that is the proper test?

5. Katzenbach v Morgan suggests that Congress should be

given the latitude to enforce a broader interpretation of the reach of

the 14th Amendment than the Supreme Court has provided--Congress may

add

to, but not subtract from, the 14th Amendment rights recognized by the

Court. Is this a sound view of Congress's 14th Amendment power,

or

do you favor the more restrictive interpretation adopted in the more

recent

cases of City of Boerne and Morrison? Why?

6. What if Congress, contrary to the Court's holding in Roe

v Wade, took the view that a fetus is "a person" for 14th Amendment

purposes and, on that basis, prohibited states from enforcing laws

authorizing

abortions? Under the theory of Katzenbach v Morgan, would

that be a valid exercise of Congress's 14th Amendment power? Why

not?

7. Robert Bork labeled Morgan "a revolutionary

constitutional

doctrine." He argued that it might authorize Congress to overturn

any

state law by simply finding that a state legislative classification

violated

the Equal Protection Clause? Is he right?

8. If, in Oregon v Mitchell, the Court had upheld the

federal law guaranteeing the right of eighteen-year-olds to vote in

state

elections, would logic have compelling the Court to also uphold a

federal

law giving the vote to seven-year-olds?

9. Is Oregon v Mitchell consistent with Katzenbach

v Morgan?

10. Should U. S. v Guest be seen as overruling the Civil

Rights Cases of 1883 on the question of whether the 14th Amendment

allows Congress to ban private discrimination?

11. Do you agree that it might be necessary to ban changes in

voting laws that have discriminatory effects on a racial group in order

to enforce the constitutional right of members of a racial group of not

being purposefully denied the right to vote?

12. Might the "compelling state interest" test of the Religious

Freedom Restoration Act struck down as applied to states in City of

Boerne still apply in cases where the free exercise of religion

claim

is asserted against federal authorities? What power in

the

Constitution might support this provision of RFRA?

13. Might Congress validly allow disabled citizens to sue states

for denial of adequate access to state facilities other than the

courtrooms involved in Tennessee v

Lane? What about voting booths? Jail

facilities? Legislative chambers and hearing rooms? Sports

arenas? Is this facility-by-facility analysis of the reach of

Congressional power justitied by the language of the Fourteenth

Amendment?

14. What do you think of Justice Scalia's opinion, expressed in

his dissent in Tennessee v Lane,

that the Court was wrong to suggest that Congress's powers under

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment ever extended beyond the power to

"enforce" rights actually guaranteed by the Amendment (not those

actions that merely threaten

rights)?

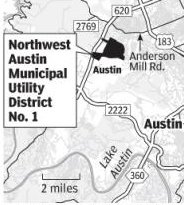

Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price and Sheriff

Lawrence Rainey

at arraignment

The Price ("Mississippi Burning") Case

In United States v Price et al (1966),

the Supreme

Court found that Congress, in the 1866 Civil Rights Act, reached

private

actors acting in concert with state officials to deprive persons of

their

constitutional rights. The Court overturned a decision throwing

out

the federal indictments brought against KKK members who participated

with

county officials in murdering three civil rights workers near

Philadelphia,

Mississippi in 1964. To read more about this fascinating case:

The

Mississippi Burning Trial

|

|