|

One of

the most perplexing of all speech-related problems

has been the issue of obscenity and what to do

about it. A wide variety of tests have been

employed by individual justices to determine what

is constitutionally proscribable obscenity, and

for long periods of time, no single approach

commanded the support of a majority of the

Court. The difficulty of defining obscenity

was memorably summarized by Justice Stewart in a

concurring opinion when he said: "I know it when I

see it." Two presidential commissions have

been formed to make recommendations on a national

response to pornography. The first

commission, The 1970 Lockhart Commission,

recommended eliminating all criminal penalities

for pornography except for pornographic depictions

of minors, or sale of pornography to minors.

Another commission appointed under President

Reagan, the Meese Commission, came to a different

conclusion, recommending continued enforcement of

laws regulating hard-core pornography, even when

only adults were involved.

For the past three decades, the courts have been concerned almost exclusively with obscene visual images, not graphic verbal descriptions of sexual activity, but such was not always the case. The early and celebrated legal battles in this country sometimes involved what are now recognized as great works of fiction that included sexual themes: books such as James Joyce's Ulysses or D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterly's Lover. But it is important to remember that obscenity issues can still involve non-visual material, as demonstrated by a Florida prosecutor's decision to (unsuccessfully) try the rap group Two Live Crew for violating Florida's obscenity statute by singing rap songs with graphic sexual lyrics. The first of our cases, Stanley v Georgia (1969), is remarkable for its unanimity. In Stanley, the Court concludes that Georgia cannot, consistent with the First Amendment, criminalize the private possession of pornography--even if the sale and distribution of that same material would not be constitutionally protected. The Court found that an individual has "a right to satisfy emotional needs in the privacy of his own house." (In 1990, however, the Court--in a 6 to 3 decision--found that constitutional protection for private possession of pornography does not extend to pornography involving children.) Smith v California concerns what must be shown to convict a bookseller in an obscenity case. The Court concludes that the First Amendment requires the government to prove more than that the bookstore contains constitutionally proscribable obscenity. The government must also prove that the bookseller knew that he was selling obscene materials so as not to have a chilling effect on speech that might be protected. Miller

v California sets out the "modern" test for

obscenity. After years in which no Supreme

Court opinion could command majority support, five

members of the Court in Miller set out a

several-part test for judging obscenity statutes:

(1) the proscribed material must depict or

describe sexual conduct in a patently offensive

way, (2) the conduct must be specifically

described in the law, and (3) the work must, taken

as a whole, lack serious value, and must appeal to

a prurient interest in sex. What is patently

offensive is to be determined by applying

community values, but any jury decision in these

cases is subject to independent constitutional

review, as the Court's decision in Jenkins v

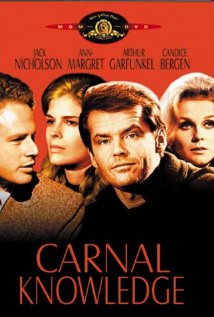

Georgia makes clear.  In Jenkins v Georgia, the U. S. Supreme Court unanimously reversed a Georgia Supreme Court decision upholding an obscenity conviction for showing the film Carnal Knowledge, starring Jack Nicholson, Ann Margret, Art Garfunkel, and Candice Bergen. In

recent years, prosecutors have focused their

attention mostly on child

pornography (out of a concern for its

effects on the minors involved) and violent

pornography (such as pornography depicting

rape). The proliferation of sexually

explicit films and images on cable television and

the Internet means, as a practical matter, the

cows have left the barn with respect to the

possibility of effectively regulating pornography

depicting the sexual activity of consenting

adults. By one estimate, there are now over

5 million websites containing sexually explicit

images. |

Stanley v. Georgia (1969)* Smith v. California (1959) Miller v. California (1973)* Jenkins v. Georgia (1974)

Questions 2. Is the Miller test sound? Because juries are free to apply community standards in determining what is obscene, speech that will be protected in say, California, may be punishable in Mississippi? Is that inconsistent with the notion that we all live under the same First Amendment? 3. Is effective regulation of obscenity even possible in the age of the Internet? 4. Should the government stop regulating sexual material depicting only consenting adults? Even if the material mixes violence and sex (say be depicting a rape)?

|