|

Prior to 1964, it was widely assumed that state tort law was completely outside of First Amendment protection. With respect to defamation law in particular, the old rule appeared to be that the Constitution extends no protection to false statements. All this changed with the landmark case of New York Times v Sullivan, a case whose importance it would be hard to overestimate. Had the case been decided against the Times, it almost certainly would have produced a more timid press and led to decisions to restrict the circulation of previously national magazines and newspapers to states unlikely to spawn financially-threatening defamation suits. In New York Times v Sullivan a unanimous Supreme Court overturns an Alabama jury award of $500,000 entered against the Times for publication of a political advertisement that allegedly defamed Montgomery County Commissioner L. B. Sullivan. At least with respect to criticism of the official conduct of public officials it is necessary, the Court said, for a defamation plaintiff to establish that a false statement has been published with either knowledge of its falsity, or with reckless disregard as to its truth or falsity. This is the so-called "actual malice" standard. In subsequent decisions, the Court extended the actual malice standard to cases involving public figures as well as public officials, reasoning that public figures assume a greater risk that they will be the subject of public scrutiny and have the means available to respond effectively to what they consider false statements about them. Time v Hill considered whether the "actual malice" standard should also apply to a false light privacy claim brought by the Hill family, who argued that they were falsely presented in a LIFE magazine story describing a play based on a crime in which they were the victims. Richard M. Nixon (between runs for the presidency) argued for the Hill family that as victims involuntarily thrown into a newsworthy event they should not have to meet the high burden of an "actual malice" test. The Court, however, disagreed, 5 to 4.

Gertz v

Welch considers

three important questions: (1) whether the full protection of the

"actual

malice" standard should extend to comments about private persons, (2)

if

not, whether the Constitution might at least limit the sorts of damages

a private individual might collect for statements on matters of public

concern made without actual

malice,

and (3) if the actual malice standard is not extended to private

individuals,

how the line should be drawn between "public figures" and "private

figures."

The Supreme Court concluded that Elmer Gertz, the plaintiff in the

defamation

action and a leading Chicago civil rights attorney, was not a public

figure

for constitutional purposes. Moreover, the Court said, as a

private

person, Gertz need only show that a defamatory falsehood was made

negligently,

not that it was made with actual malice. Finally--in what turned

out to be a major victory for the media--the Court ruled that in the

absence of a showing of actual malice, private plaintiffs are limited

by

the First Amendment--at least with respect to comments about a matter

of

public concern-- to recovery only for actual damages, and not for

punitive

or presumed damages. In its 1985

decision in Dun & Bradstreet v

Greeenmoss Builders, the Court provided its answer to the last

major constitutional question in the defamation area: what damages are

available to a private person (or corporation, in this case) when the

false statement of fact does not relate to a matter of public

concern? Distinguishing Gertz,

which did involve false statements relating to a matter of public

concern, the Court (5 to 4) found that Greenmoss Builders was entitled

to collect punitive damages when a credit-rating report falsely and

negligently stated that the company had filed a petition for

bankruptcy. The Court concluded that the First Amendment interest

in protecting false statements was substantially less when the

statements did not relate to matters of public concern. Of

course, the decision in Dun &

Bradstreet has the effect of requiring courts to draw a

sometimes difficult line between statements relating and not relating

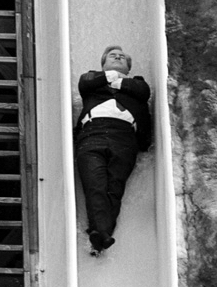

to matters of public concern. [see DEFAMATION CHART] Hugo Zacchini ("The Human Cannonball") was the plaintiff in Zacchini v Scripps-Howard. Zacchini sued Scripps-Howard, the owner of an Ohio television station, when--over Zacchini's objections--it filmed, and then broadcast on the evening news, Zacchini's act of being shot out of a cannon at a county fair. The Supreme Court sided with Hugo, ruling 5 to 4 that the First Amendment is not offended when liability (using a "right-of-publicity" theory) is imposed for broadcasting an entertainer's "entire act."   Rev. Jerry Falwell, the plaintiff in Hustler v Falwell, going down a waterslide in 1987. LINK TO FALWELL V FLYNT TRIAL SITE  Woody Harrelson played Hustler publisher Larry Flynt in a movie about the Falwell v Hustler case. Finally, Cohen v Cowles Media considered whether the First Amendment protects a media defendant who first promises a source confidentiality, then discloses the name of the source in a newsworthy story. The Court, 5 to 4, ruled that when liability is based on a generally applicable law (here, the common law as it relates to promissory estoppel) the First Amendment is not violated--even when the disclosure of the source was accurate and newsworthy. |

New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) Gertz v. Welch (1974) Zacchini v Scripps-Howard (1977) Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988) Cohen v. Cowles Media Co. (1991)

Image

of the advertisement involved in N.

Y. Times v Sullivan Text of the adverstisement

involved in N. Y. Times v.

Sullivan Large image of advertisement involved in Hustler Magazine v Falwell

Questions 2. How many of the 394 Alabamans that received the New York Times were likely to have read the advertisement involved in N. Y. Times v Sullivan, linked the alleged defamatory statements to L. B. Sullivan, and--as a result--lowered their own opinion about how well Sullivan was doing his job? 3. Do you agree with Justice Black's comment that in Alabama in the 1960s, the statements alleged to be defamatory were more likely to enhance his reputation than to diminish it? 4. For purposes of applying the actual malice standard, who should be considered public officials? A county prosecutor? A public defender? A dogcatcher? A receptionist in the mayor's office? 5. For purposes of applying the actual malice standard, what should be considered comment concerning official conduct? A story about a governor's drunken behavior at a party? A story about a governor's habit of having two-martini lunches? A story about an affair that a governor is having? 6. What do you think about the suggestion of three justices in Sullivan that even deliberate lies about public officials should be protected by the First Amendment? 7. In what way was the Hill family injured by the LIFE magazine story inaccurately describing their experience as hostages? 8. Would the Hill family have prevailed if it could show LIFE made up non-defamatory quotes (e.g., "You'll never get away with this" or "Get away from me, you brute") and falsely attributed them to Hill family members? 9. Should it matter to the constitutional analysis in Time v Hill that the Hill family involuntarily became participants in the newsworthy event? 10. Why should public officials and public figures have to show a higher degree of media defendant fault in defamation cases than private figures? 11. After Gertz, states are free to set their own standards of proof in defamation cases involving private figure plaintiffs--provided that the standard is at least negligence (not just strict liability). Several states have set higher standards, ranging from actual malice to gross negligence. Which states would you expect to be most likely to opt for stricter standards of proof? 12. What should a newspaper do to minimize its risk of liability in defamation cases? Should a paper, for example, distribute guidelines for fact-checking to its reporters--or would this be a bad idea? 13. Overall, is Gertz a good or a bad decision for the press? 14. The Court stressed in Zacchini that the television station showed his entire act. What is an entire act? Why is it just the 15 seconds between takeoff and landing, and not the fanfare before the lighting of the cannon? 15. If Zacchini were to have missed the net and broken his legs, could the station have broadcast the entire act? 16. Would the First Amendment have protected the station in Zacchini if Hugo was shot out of a cannon in a public park? 17. Is it critical to the outcome of the case in Zacchini that Hugo asked the station not to film his act? 18. Do you see any sound principle that would protect political cartoons, Jay Leno jokes, and Saturday Night Life satire, but would allow liability to be imposed against Hustler for a parody ad such as it ran about Rev. Falwell? 19. What exactly is "a generally applicable law" (Cohen) such as might allow liability to be imposed against media defendants, just as other defendants? Trespass laws are an obvious example. But why isn't the law of intentional infliction of emotional distress (as involved in Hustler v Falwell) a generally applicable law--it applies to stalkers and obscene phone callers as well as media defendants? |