|

Modern First Amendment law can be said to have been born in a series of World War I era prosecutions for violation of the Espionage Act of 1917. Although First Amendment claimants in those cases were 0 for 6 in the Supreme Court, their challenges sparked a debate within the Court that would eventually lead to a much more speech-protective jurisprudence. The first of our cases, Schenck v United States, involves an appeal of the general secretary of the American Socialist Party, who had been convicted for distributing 15,000 leaflets to young men of draft age critical of the war effort and, especially, the draft. The leaflet urged readers to "Assert your rights--Do not submit to intimidation." Writing for the Court in Schenck, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes asked whether "the words create a clear and present danger that they will bring about substantive evils Congress has a right to prevent?" As used in Schenck, Holmes's test seemed to demand little more than that the government show that the words in the leaflet had a bad tendency--no proof was demanded that the words actually persuaded anyone to evade the draft, or even that they were highly likely to have that effect. Schenck's conviction was upheld. Debs v

United States

involved a speech, "Socialism is the Answer," given by Socialist

Eugene Debs in 1918 before 1,200 persons in Ohio. Debs was

prosecuted

for remarks such as: "I might not be able to say all that I think, but

you need to know that you are fit for something better than slavery and

common fodder." Even though Debs's speech was milder than some

made,

for example, by George McGovern about the Viet Nam War during his 1972

presidential bid, the Supreme Court--again using its weak form of the

clear-and-present-danger

test (Does the speech have a bad tendency?)--voted to uphold the

conviction

and Deb's ten-year sentence.

In Abrams

v United

States we see the beginnings of a movement to a more

speech-protective

test. Although the Court majority votes to uphold the Espionage

Act

convictions of Jacob Abrams and other anarchists who distributed

leaflets

attacking the U. S.'s decision to send troops to Europe to defend

Czarist

Russia against the Bolsheviks, Justices Holmes and Brandeis publish a

powerful

dissenting opinion. Holmes argued that the "silly leaflet" of

"poor

and puny anonymities" posed no real danger to U. S. efforts, and thus

failed

to present a "clear and present danger" that the government might be

justified

in trying to suppress. Writing that "the best test of truth is

competition

in the market" of ideas, Holmes urged his brethren to take their

responsibities

to enforce the First Amendment more seriously.

Holmes and Brandeis dissent again in Gitlow v New York, a case involving the publication of "Left Wing Manifesto," a paper urging general strikes and critical of moderates who would seek changes only through the ballot box. The Court upholds Gitlow's conviction, but significantly the Court agrees with Gitlow's position that states (as well as the federal government) are bound to comply with the commands of the First Amendment, as the protections have been "incorporated" through the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court never again would question the applicability of the free speech protections to states. In their dissent, Holmes and Brandeis argue that abstract advocacy of the form appearing in the "Manifesto" is protected by the First Amendment, and that the government must show that speech presents a real and immediate danger in order to be punishable. Cases

|

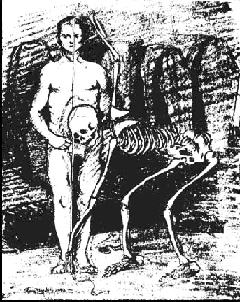

Questions 2. Did the leaflet involved in Schenck incite young men to evade the draft? Is it likely that the leaflet would convince some young men to evade the draft? Should both of these things have to be shown to sustain a prosecution against a First Amendment challenge? How much proof of obstructive effect should be required? 3. The proposed test of Holmes and Brandeis in their Abrams dissent would require that the government show that the speech in question pose some real and immediate threat to U. S. war efforts--the fact that the speech might have a bad tendency is not enough. Does the Holmes test offer more First Amendment protection for ineffective speech by "anonymities" than effective speech by "somebodies"? If so, is this a good result? 4. The Holmes dissent in Abrams is recognized as one of the great judicial opinions of all time. Do you agree? What makes it great?  "Conscription" [a skeleton tape measures a draftee] Cartoon by H. J. Glintenkamp from August 1917 issue of The Masses. This cartoon was one of three cited by the Postmaster as violating the Espionage Act (see below). CLICK TO IMAGE OF COVER OF THE AUGUST 1917 ISSUE |