by Lawrence MacLachlan

|

http://www.hcourt.gov.au/speeches/kirbyj/kirbyj_charle88.htm

The

official biography chronicles the controversies and

disputes of Charles’ reign which eventually led to war with the Scots

and then

within The Trial of King Charles I –

Defining Moment

for our Constitutional Liberties: The Hon Justice Michael Kirby

AC CMG , Anglo-Australian Lawyers Association, London-Great Hall, Grays

Inn,

January 22, 1999 on the 350th anniversary of the execution

of King

Charles. (Justice of the High Court of “The trial and execution of a king is a

remarkable event in

the history of any nation. The trial and execution of a King of England

is so

extraordinary a happening, in one of the world's oldest and most

successful

monarchies, that it ought not to be forgotten. The trial and execution

of King

Charles I, in many ways a cultivated and intelligent monarch and a

devout

family man, shocked the world in which it occurred. It interrupted the

continuity of English monarchy with a period of military and populist

rule that

forever cured “And yet the assertion by the Commons House

of the English

Parliament of its powers over the King established a principle, written

in the

King's blood, which altered for all time the character of the monarchy,

the

Parliament and the relations between each. The vivid events of the

trial and

execution which followed, meant that no absolute monarch could again

successfully claim the autocratic powers which King Charles I had

enjoyed.

These facts had profound consequences far from From the Epilogue: “The trial of King Charles I was, by legal standards, a discreditable affair . The "Court" had no legal authority. It was the creature of the power of the army. The King had no advance notice of the charge. No one was appointed to help him with his defence. The court did not even pretend to be impartial. When the King scored a point in argument, the soldiers around the Hall showed where the real power lay. Eventually the King's refusal to answer was deemed not to be a plea of not guilty (requiring the accuser to prove the charge) but a plea of guilty to treason. This can only be understood by acceptance with the criminal procedures of the time.” “By the standards of today, many fundamental rights were

breached or ignored

in the way King Charles' trial was conducted....The King was denied the

chance

to appeal to a true Parliament.... His deprivation of

liberty, and ultimately of his life, was by the power of a purported

Parliament

and not by a procedure established by law. He was not

informed at the time of his arrest of the charges against him... Nor

was he brought promptly before a judge or other

officer authorised by law to exercise the judicial power....

He had no access to a court to invoke the Great Writ to secure his

liberty. Although he was treated with courtesy and dignity, he

was not treated with humanity. He was kept away from

his family, friends and advisers. He was surrounded by guards,

informers and

pimps engaged by the army for surveillance.” “In his trial, King Charles I was not treated as an equal

before the courts

in that he was not put on trial in one of the regular courts of the

land... The King was expressly denied the presumption of

innocence....Many other rights of due process, which

we take for granted, were denied to him. The right to be informed of

the charge

and to have adequate time and facilities to prepare his defence and to

communicate with advisers; the right to be tried

without delay; the right to examine or have examined

the witnesses against him who gave their testimony before a committee

of the

Court, and the right not to be compelled to testify

against himself or to confess his guilt . He had no

right to have his conviction and sentence reviewed by a higher tribunal

according to law. The only higher tribunal to which

he ultimately appealed was the English people to whom he spoke directly

from

the scaffold.” “On the other hand, it is worth noting that the

revolutionaries made efforts

to give a semblance of justice to the proceedings. The fact that they

felt an

obligation to conduct a trial at all is noteworthy. It is a reflection

of the

power of the trial process upon the imagination of the English people

even at

that time.” “The trial was conducted in public, at least as to

those parts which the King attended. It was known by the judges and the

prisoner that reporters were present, and in the state of the

newspapers of the

time, that they would carry the King's words to the public. This was no

chaotic

brutality such as brought an end to the monarchy of “Without the trial of the King, it is inconceivable that the Glorious Revolution of 1688 would have taken place. Yet it is that revolution which finally established the system of limited or constitutional monarchy as a conditional and generally symbolic form of government, always ultimately answerable to the will of the people.... Without the Glorious Revolution, there would probably have been no American Revolution in 1766....” “Each of these protagonists of 350 years ago had a lesson for

our time. The

one of the merit of continuity, legitimacy, history, the rule of law

and of

ancient liberties. The other the message of the sovereignty of the

people, the

importance of the parliamentary institutions, the legitimacy of

democracy and

the right of a people even to end an ancient monarchy if that is

necessary to defend

their own sovereign demands...” http://www.hcourt.gov.au/speeches/kirbyj/kirbyj_charle88.htm Act

Erecting a

High Court of Justice for the Trial of Charles I

WHEREAS it is notorious that Charles Stuart, the now King of England, not content with those many encroachments which his predecessors had made upon the people in their rights and freedoms, hath had a wicked design totally to subvert the ancient and fundamental laws and liberties of this nation, and in their place to introduce an arbitrary and tyrannical government, and that besides all other evil ways and means to bring this design to pass, he hath prosecuted it with fire and sword, levied and maintained a civil war in the land, against the Parliament and kingdom; whereby the country hath been miserably wasted, the public treasure exhausted, trade decayed, thousands of people murdered, and infinite other mischiefs committed; for all which high and treasonable offences the said Charles Stuart might long since justly have been brought to exemplary and condign punishment; whereas also the Parliament, well hoping that the restraint and imprisonment of his person, after it had pleased God to deliver him into their hands, would have quieted the distempers of the kingdom, did forbear to proceed judicially against him, but found, by sad experience, that such their remissness served only to encourage him and his accomplices in the continuance of their evil practices, and in raising new commotions, rebellions and invasions: for prevention therefore of the like or greater inconveniences, and to the end no Chief Officer or Magistrate whatsoever may hereafter presume, traitorously and maliciously to imagine or contrive the enslaving or destroying of the English nation, and to expect impunity for so doing; be it enacted and ordained by the Commons in Parliament and it is hereby enacted and ordained by the authority thereof that Thomas, Lord Fairfax, Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton [* * * 135 names in all], shall be and are hereby appointed and required to be Commissioners and judges for the hearing, trying and adjudging of the said Charles Stuart; and the said Commissioners, or any twenty or more of them, shall be, and are hereby authorised and constituted an High Court of Justice, to meet and sit at such convenient time and place as by the said Commissioners, or the major part of twenty or more of them, under their hands and seals, shall be appointed and notified by public proclamation in the Great Hall or Palace Yard of Westminster; and to adjourn from time to time, and from place to place, as the said High Court, or the major part thereof meeting, shall hold fit; and to take order for the charging of him, the said Charles Stuart, with the crimes and treasons above mentioned, and for receiving his personal answer thereunto, and for examination of witnesses upon oath (which the Court hath hereby authority to administer) or otherwise, and taking any other evidence concerning the same; and thereupon, or in default of such answer, to proceed to final sentence according to justice and the merit of the cause; and such final sentence to execute, or cause be to executed, speedily and impartially. And the said Court is hereby authorised and required to

appoint and direct

all such officers, attendants and other circumstances as they, or the

major

part of them, shall in any sort judge necessary or useful for the

orderly and

good managing of the premises. And Thomas, Lord Fairfax, the General,

and all

officers and soldiers under his command, and all officers of justice,

and other

well-affected persons, are hereby authorised and required to be aiding

and

assisting unto the said Court in the due execution of the trust hereby

committed. Provided that this Act, and the authority hereby granted, do

continue in force for the space of one month from the date of the

making

hereof, and no longer. (Passed the Commons, January 6, 1648/9.

Rushworth

viii. 1379.) http://home.freeuk.net/don-aitken/ast/c1b.html#210 Excerpts

of Charles’ Defence at Trial, January 20 –

27, 1649 “I would know by what power I am called hither ... I would know by what authority, I mean lawful; there are many unlawful authorities in the world;thieves and robbers by the high-ways ... Remember, I am your King, your lawful King, and what sins you bring upon your heads, and the judgement of God upon this land. Think well upon it, I say, think well upon it, before you go further from one sin to a greater ... I have a trust committed to me by God, byold and lawful descent, I will not betray it, to answer a new unlawful authority;therefore resolve me that, and you shall hear more of me. I do stand more for the liberty of my people, than any here that come to be mypretended judges ... I do not come here as submitting to the Court. I will standas much for the privilege of the House of Commons, rightly understood, asany man here whatsoever: I see no House of Lords here, that may constitutea Parliament ... Let me see a legal authority warranted by the Word of God,the Scriptures, or warranted by the constitutions of the Kingdom, and I will answer. It is not a slight thing you are about. I am sworn to keep the peace, by that duty I owe to God and my country; and I will do it to the last breath of my body. And therefore ye shall do well to satisfy, first, God, and then the country, by what authority you do it. If you do it by an usurped authority, you cannot answer it; there is a God in Heaven, that will call you, and all that give you power, to account. If it were only my own particular case, I would have satisfied myself with the protestation I made the last time I was here, against the legality of the Court, and that a King cannot be tried by any superior jurisdiction on earth: but it is not my case alone, it is the freedom and the liberty of the people of England; and do you pretend what you will, I stand more for their liberties. For if power without law, may make laws, may alter the fundamental laws of the Kingdom, I do not know what subject he is in England that can be sure of his life, or any thing that he calls his own. I do not know the forms of law; I do know law and reason, though I am no lawyer professed: but I know as much law as any gentleman in England, and therefore, under favour, I do plead for the liberties of the people of England more than you do; and therefore if I should impose a belief upon any man without reasons given for it, it were unreasonable ... The Commons of England was never a Court of Judicature; I would know how they came to be so. It

was the liberty, freedom, and laws of the subject that ever I took –

defended myself

with arms. I never took up arms against the people, but for the laws

...For the

charge, I value it not a rush. It is the liberty of the people of my own particular ends, makes me now at least desire, before sentence be given, that I may be heard ... before the Lords and Commons ... If I cannot get this liberty, I do protest, that these fair shows of liberty and peace are pure shows and that you will not hear your King. http://www.royal.gov.uk/pdf/charlesi.pdf High

Court of Justice President Bradshaw’s Statement to Charles at the

Conclusion

of the Trial 'there is a contract

and a bargain made

between the King and his people, and your oath is taken: and certainly,

Sir,

the bond is reciprocal; for as you are the liege lord, so they liege

subjects

... This we know now, the one tie, the one bond, is the bond of

protection that

is due from the sovereign; the other is the bond of subjection that is

due from

the subject. Sir, if this bond be once broken, farewell sovereignty!

... These

things may not be denied, Sir ... Whether you

have been, as by your

office you ought to be, a protector of England, or the destroyer of

England,

let all England judge, or all the world, that hath look'd upon it ...

You

disavow us as a Court; and therefore for you to address yourself to us,

not

acknowledging as a Court to judge of what you say, it is not to be

permitted.

And truth is, all along, from the first time you were pleased to

disavow disown

us, the Court needed not to have heard you one word.”

The Clerk to the Court concluded with the

sentence 'this Court doth adjudge that he the said Charles Stuart, as a

Tyrant,

Traitor, Murderer and Public Enemy to

the good people of this

Nation, shall be put to death, by the severing his head from his body'.

Bradshaw refused to allow the King to speak in Court after sentence (as

a

prisoner condemned was already dead in law), and the King was led away

still protesting. “I am not

suffered to speak; expect

what justice other people will have.” http://www.royal.gov.uk/pdf/charlesi.pdf Sentence

of the

High Court of Justice upon Charles I

WHEREAS the Commons of England assembled in Parliament, have by their late Act entitled ‘An Act of the Commons of England, assembled in Parliament, for erecting an High Court of Justice for the trying and judging of Charles Stuart, King of England,’ authorised and constituted us an High Court of Justice for the trying and judging of the said Charles Stuart for the crimes and treasons in the said Act mentioned; by virtue whereof the said Charles Stuart hath been three several times convented before this High Court, where the first day, being Saturday, the 20th of January, instant, in pursuance of the said Act, a charge of high treason and other high crimes was, in the behalf of the people of England, exhibited against him, and read openly unto him, wherein he was charged, that he, the said Charles Stuart, being admitted King of England, and therein trusted with a limited power to govern by, and according to the law of the land, and not otherwise, and by his trust, oath, and office, being obliged to use the power committed to him for the good and benefit of the people, and for the preservation of their rights and liberties; yet, nevertheless, out of a wicked design to erect and uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people, and to take away and make void the foundations thereof and of all redress and remedy of misgovernment, which by the fundamental constitutions of this kingdom were reserved on the people’s behalf in the right and power of frequent and successive Parliaments, or national meetings in Council; he, the said Charles Stuart, for accomplishment of such his designs, and for the protecting of himself and his adherents in his and their wicked practices, to the same end hath traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament and people therein represented, as with the circumstances of time and place is in the said charge more particularly set forth; and that he hath thereby caused and procured many thousands of the free people of this nation to be slain; and by divisions, parties, and insurrections within this land, by invasions from foreign parts, endeavoured and procured by him, and by many other evil ways and means, he, the said Charles Stuart, hath not only maintained and carried on the said war both by sea and land, but also hath renewed, or caused to be renewed, the said war against the Parliament and good people of this nation in this present year 1648, in several counties and places in this kingdom in the charge specified; and that he hath for that purpose given his commission to his son, the Prince, and others, whereby, besides multitudes of other persons, many such as were by the Parliament entrusted and employed for the safety of this nation, being by him or his agents corrupted, to the betraying of their trust, and revolting from the Parliament, have had entertainment and commission for the continuing and renewing of the war and hostility against the said Parliament and people: and that by the said cruel and unnatural war so levied, continued and renewed, much innocent blood of the free people of this nation hath been spilt, many families undone, the public treasure wasted, trade obstructed and miserably decayed, vast expense and damage to the nation incurred, and many parts of the land spoiled, some of them even to desolation; and that he still continues his commission to his said son, and other rebels and revolters, both English and foreigners, and to the Earl of Ormond, and to the Irish rebels and revolters associated with him, from whom further invasions of this land are threatened by his procurement and on his behalf; and that all the said wicked designs, wars, and evil practices of him, the said Charles Stuart, were still carried on for the advancement and upholding of the personal interest of will, power, and pretended prerogative to himself and his family, against the public interest, common right, liberty, justice, and peace of the people of this nation: and that he thereby hath been and is the occasioner, author, and continuer of the said unnatural, cruel, and bloody wars, and therein guilty of all the treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damage, and mischief to this nation, acted and committed in the said wars, or occasioned thereby; whereupon the proceedings and judgment of this Court were prayed against him, as a tyrant, traitor, and murderer, and public enemy to the Commonwealth, as by the said charge more fully appeareth. To which charge, being read unto him as aforesaid, he, the said Charles Stuart, was required to give his answer, but he refused so to do; and upon Monday, the 22nd day of January instant, being again brought before this Court, and there required to answer directly to the said charge, he still refused so to do; whereupon his default and contumacy was entered; and the next day, being the third time brought before the Court, judgment was then prayed against him on the behalf of the people of England for his contumacy, and for the matters contained against him in the said charge, as taking the same for confessed, in regard of his refusing to answer thereto. Yet notwithstanding this Court (not willing to take advantage of his contempt) did once more require him to answer to the said charge; but he again refused so to do; upon which his several defaults, this Court might justly have proceeded to judgment against him, both for his contumacy and the matters of the charge, taking the same for confessed as aforesaid. Yet nevertheless this Court, for its own clearer information and further satisfaction, have thought fit to examine witnesses upon oath, and take notice of other evidences, touching the matters contained in the said charge, which accordingly they have done. Now, therefore, upon serious and mature deliberation of the

premises, and

consideration had of the notoriety of the matters of fact charged upon

him as

aforesaid, this Court is in judgment and conscience satisfied that he,

the said

Charles Stuart, is guilty of levying war against the said Parliament

and

people, and maintaining and continuing the same; for which in the said

charge

he stands accused, and by the general course of his government,

counsels, and

practices, before and since this Parliament began (which have been and

are

notorious and public, and the effects whereof remain abundantly upon

record)

this Court is fully satisfied in their judgments and consciences, that

he has

been and is guilty of the wicked designs and endeavours in the said

charge set

forth; and that the said war hath been levied, maintained, and

continued by him

as aforesaid, in prosecution, and for accomplishment of the said

designs; and

that he hath been and is the occasioner, author, and continuer of the

said

unnatural, cruel, and bloody wars, and therein guilty of high treason,

and of

the murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damage, and

mischief to

this nation acted and committed in the said war, and occasioned

thereby. For

all which treasons and crimes this Court doth adjudge that he, the said

Charles

Stuart, as a tyrant, traitor, murderer, and public enemy to the good

people of

this nation, shall be put to death by the severing of his head from his

body. (1648/9,

January 27. Rushworth, viii. 1420. Gardiner, 377-380.) http://home.freeuk.net/don-aitken/ast/c1b.html#211 The

Death Warrant

of Charles I

At the High Court of Justice for the trying and judging of

Charles

Stuart, King of England, Jan. 29, Anno Domini 1648. WHEREAS Charles Stuart, King of England, is, and standeth

convicted,

attainted, and condemned of high treason, and other high crimes; and

sentence

upon Saturday last was pronounced against him by this Court, to be put

to death

by the severing of his head from his body; of which sentence, execution

vet

remaineth to be done: these are therefore to will and require you to

see the

said sentence executed in the open street before Whitehall, upon the

morrow,

being the thirtieth day of this instant month of January, between the

hours of

ten in the morning and five in the afternoon of the same day, with full

effect.

And for so doing this shall be your sufficient warrant. And these are

to

require all officers, soldiers, and others, the good people of this

nation of To Col. Francis Hacker, Col. Huncks, and Lieut-Col. Phayre, and to every of them. Given under our hands and seals. House of Lords Record Office : The Death Warrant of King Charles I At the high Co[ Whereas Charles Steuart Kinge of England is and standeth

convicted attaynted

and condemned of High Treason and other high Crymes, And sentence uppon

Saturday last was pronounced against him by

this

Co[ur]t to be putt to death by the severinge of his head from his body

Of

w[hi]ch sentence execuc[i]on yet remayneth to be done, These are

therefore to

will and require you to see the said sentence executed In the

open Streete before Whitehall uppon the morrowe being the Thirtieth day

of this

instante moneth of January betweene the houres of Tenn in the morninge

and Five

in the afternoone of the same day w[i]th full effect And for soe doing

this

shall be yo[u]r sufficient warrant And these are to require All

Officers and

Souldiers and other the good people of this Nation of England to be

assistinge

unto you in this service Given under o[ur] hands and

Seales http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld199899/ldparlac/ldrpt66.htm The

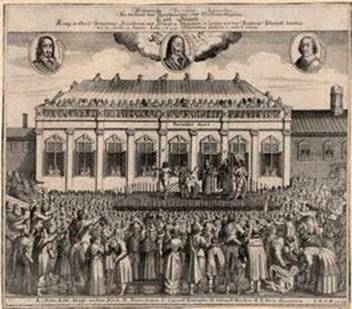

Execution of King Charles from the National

Portrait Gallery

Last Words: On

20 January, 1649 Charles was charged with high treason

'against the realm of The

King was sentenced to death on 27 January. Three days

later, January 30, 1649 Charles was beheaded on a scaffold outside the

Banqueting House in On

the scaffold, he repeated his case: 'I must tell you that

the liberty and freedom [of the people] consists in having of

Government, those

laws by which their life and their goods may be most their own. It is

not for

having share in Government, Sir, that is nothing pertaining to them. A

subject

and a sovereign are clean different things. If I would have given way

to an

arbitrary way, for to have all laws changed according to the Power of

the

Sword, I needed not to have come here, and therefore I tell you ...

that I am

the martyr of the people.' His final

words were 'I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown, where no

disturbance can be.' http://www.royal.gov.uk/HistoryoftheMonarchy/KingsandQueensoftheUnitedKingdom/TheStuarts/CharlesI.aspx Act

Abolishing

the Office of King

WHEREAS Charles Stuart, late King of England, Ireland, and the territories and dominions thereunto belonging, hath by authority derived from Parliament been and is hereby declared to be justly condemned, adjudged to die, and put to death, for many treasons, murders, and other heinous offences committed by him, by which judgment he stood, and is hereby declared to be, attainted of high treason, whereby his issue and posterity, and all others pretending title under him, are become incapable of the said Crown, or of being King or Queen of the said kingdom or dominions, or either or any of them; be it therefore enacted and ordained, and it is enacted, ordained, and declared by this present Parliament, and by authority thereof, that all the people of England and Ireland, and the dominions and territories thereunto belonging, of what degree or condition soever, are discharged of all fealty, homage, and allegiance which is or shall be pretended to be due unto any of the issue and posterity of the said late King, or any claiming under him; and that Charles Stuart, eldest son, and James, called Duke of York, second son, and all other the issue and posterity of him the said late King, and all and every person and persons pretending title from, by, or under him, are and be disabled to hold or enjoy the said Crown of England and Ireland, and other the dominions thereunto belonging, or any of them; or to have the name, title, style, or dignity of King or Queen of England and Ireland, Prince of Wales, or any of them; or to have and enjoy the power and dominion of the said kingdom and dominions, or any of them, or the honours, manors, lands, tenements, possessions, and hereditaments belonging or appertaining to the said Crown of England and Ireland, and other the dominions aforesaid, or to any of them; or to the Principality of Wales, Duchy of Lancaster or Cornwall, or any or either of them, any law, statute, ordinance, usage, or custom to the contrary hereof in any wise notwithstanding. II. And whereas it is and hath been found by experience, that the office of a King in this nation and Ireland, and to have the power thereof in any single person, is unnecessary, burdensome, and dangerous to the liberty, safety, and public interest of the people, and that for the most part, use hath been made of the regal power and prerogative to oppress and impoverish and enslave the subject; and that usually and naturally any one person in such power makes it his interest to encroach upon the just freedom and liberty of the people, and to promote the setting up of their own will and power above the laws, that so they might enslave these kingdoms to their own lust; be it therefore enacted and ordained by this present Parliament, and by authority of the same, that the office of a King in this nation shall not henceforth reside in or be exercised by any one single person; and that no one person whatsoever shall or may have, or hold the office, style, dignity, power, or authority of King of the said kingdoms and dominions, or any of them, or of the Prince of Wales, any law, statute, usage, or custom to the contrary thereof in any wise notwithstanding. III. And it is hereby enacted, that if any person or persons shall endeavour to attempt by force of arms or otherwise, or be aiding, assisting, comforting, or abetting unto any person or persons that shall by any ways or means whatsoever endeavour or attempt the reviving or setting up again of any pretended right of the said Charles, eldest son to the said late King, James called Duke of York, or of any other the issue and posterity of the said late King, or of any person or persons claiming under him or them, to the said regal office, style, dignity, or authority, or to be Prince of Wales; or the promoting of any one person whatsoever to the name, style, dignity, power, prerogative, or authority of King of England and Ireland, and dominions aforesaid, or any of them; that then every such offence shall be deemed and adjudged high treason, and the offenders therein, their counsellors, procurers, aiders and abettors, being convicted of the said offence, or any of them, shall be deemed and adjudged traitors against the Parliament and people of England, and shall suffer, lose, and forfeit, and have such like and the same pains, forfeitures, judgments, and execution as is used in case of high treason. IV. And whereas by the abolition of the kingly office provided for in this Act, a most happy way is made for this nation (if God see it good) to return to its just and ancient right, of being governed by its own Representatives or national meetings in council, from time to time chosen and entrusted for that purpose by the people, it is therefore resolved and declared by the Commons assembled in Parliament, that they will put a period to the sitting of this present Parliament, and dissolve the same so soon, as may possibly stand with the safety of the people that hath betrusted them, and with what is absolutely necessary for the preserving and upholding the Government now settled in the way of a Commonwealth; and that they will carefully provide for the certain choosing, meeting, and sitting of the next and future Representatives, with such other circumstances of freedom in choice and equality in distribution of members to be elected thereunto, as shall most conduce to the lasting freedom and good of this Commonwealth. V. And it is hereby further enacted and declared, notwithstanding anything contained in this Act, no person or persons of what condition and quality soever, within the commonwealth of England and Ireland, dominion of Wales, the islands of Guernsey and Jersey, and town of Berwick-upon-Tweed, shall be discharged from the obedience and subjection which he and they owe to the Government of this nation, as it is now declared, but all and every of them shall in all things render and perform the same, as of right is due unto the supreme authority hereby declared to reside in this and the successive Representatives of the people of this nation, and in them only. (1648/9, March 17. Scobell, ii. 7. Gardiner 384-387.) http://home.freeuk.net/don-aitken/ast/cp.html#214 Act Abolishing the House of Lords

THE Commons of England assembled in Parliament, finding by too long experience that the House of Lords is useless and dangerous to the people of England to be continued, have thought fit to ordain and enact, and be it ordained and enacted by this present Parliament, and by the authority of the same, that from henceforth the House of Lords in Parliament shall be and is hereby wholly abolished and taken away; and that the Lords shall not from henceforth meet or sit in the said House called the Lords’ House, or in any other house or place whatsoever, as a House of Lords; nor shall sit, vote, advise, adjudge, or determine of any matter or thing whatsoever, as a House of Lords in Parliament: nevertheless it is hereby declared, that neither such Lords as have demeaned themselves with honour, courage, and fidelity to the Commonwealth, nor their posterities who shall continue so, shall be excluded from the public councils of the nation, but shall be admitted thereunto, and have their free vote in Parliament, if they shall be thereunto elected, as other persons of interest elected and qualified thereunto ought to have. II. And be it further ordained and enacted by the authority

aforesaid, that

no Peer of this land, not being elected, qualified and sitting in

Parliament as

aforesaid, shall claim, have, or make use of any privilege of

Parliament,

either in relation to his person, quality, or estate, any law, usage,

or custom

to the contrary notwithstanding.

(1648/9, March 19.

Scobell ii. 8. Gardiner 387, 388) http://home.freeuk.net/don-aitken/ast/cp.html#215 Act

Declaring

|

John Bradshaw |

Oliver Cromwell |

Henry Ireton |

Additional

Charles Carlton, Charles I, the

personal monarch.

Richard Cust. Charles I: a political

life.

Issac Disraeli, Commentaries on the

life and reign of Charles the First, King of

Peter Donald, An uncounselled king:

Charles I and the Scottish troubles, 1637-1641.

Ian Gentles, The English Revolution

and the wars in the three kingdoms, 1638-1652.

Caroline Hibbard. Charles I and the

popish plot. Chapel Hill;

Clive Holmes. Why was Charles I

executed?

D. L. Keir, The Constitutional History of Modern

David Lagomarsino and Charles T. Wood eds. The

Trial of Charles I; a documentary history.

James F. Larkin ed. Royal

proclamations of King Charles I, 1625-1646.

John Macleod, Dynasty: the Stuarts,

1560-1807.

J. de Morgan, "The Most Notable Trial in Modern History" in H W Fuller (ed) The Green Bag, vol xi, 1899, Boston.

J.G. Muddiman ed. Trial of King

Charles the First.

Brian Quintrell. Charles I, 1625-1640.

Trevor Royle, The British Civil War:

the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, 1638-1660.

Kevin Sharpe. The personal rule of

Charles I.

Louis J. SiricoJr. “The Trial of Charles I: A Sesquitricentennial Reflection” 16 Constitutional Commentary 51 (1999) http://ssrn.com/abstract=177088

C. V. Wedgewood, The Trial of Charles I, Penguin, 1964.

G.M. Young. Charles I and Cromwell; an

essay.