|

Famous Medieval Trials by Doug Linder (2017) God as

Judge: Medieval Trials Great and Gruesome The year is

897, and Pope Stephen VI has ordered the

eight-month-old corpse of his predecessor removed

from its vault at St. Peter’s. The

former, and very dead, pope is clad in his old

pontifical vestments, placed on a throne in a

Roman basilica, and put on trial. A few

decades later, at least if you believe the Annals

of Winchester, King Edward the Confessor accuses

his mother of adultery. But

Edward’s mother proves her innocence by walking

barefoot and unharmed over red-hot ploughshares. Fast

forward to 1386, in Paris, where the King and

Parliament decide to resolve charges of rape and

defamation by having the accused and his accuser

mount horses for a jousting battle. The two

men will go at it until one or the other is dead. Whoever

wins the battle, all agree, will be vindicated as

a matter of law. Strange

doings. Medieval

trials

seem very curious to the modern mind. And today

we’re going to survey three of these peculiar

trials—three great and gruesome trials, spanning

roughly a half millennium. Our goal

is to make sense--if sense can be made--of the

unusual means for resolving conflicts and

punishing bad actors in The Middle Ages. What

were these people thinking? How did it come

to this? Ancient

Greece and Ancient Rome each had pragmatic and

evidence-driven methods for resolving disputes and

criminal charges.

What happened? What happened,

in the first half of the sixth century, was that a

curtain fell on the ancient world. In the

530s, the Black Death swept through much of

Europe. Soon marauding barbarians entered the

continent. They

killed, conquered, and converted. And, in

the process, the invaders transformed Europe’s

systems of justice.

The relatively sensible approach to crime

found in Ancient Rome gave way to something much

different. The Cadaver

Synod of 897  Our tour of

the strange world of medieval justice starts with

The Cadaver Synod of 897. Or, as

many have come to call it, “The Dead Pope Trial.” The mid to

late 800s was a bad time for popes. Charlemagne’s

empire had crumbled and Europe had split into

smaller and smaller fiefdoms. Many of

these fiefdoms eyed Rome’s treasury and sought

protection money.

Because of Rome’s weakened condition, popes

in the late 800s depended on the support of

secular leaders to hold office and to achieve

goals. It

was a time of political factions. A pope

had to be aligned with the right faction to

accomplish much of anything. But when an

opening occurred in 872, the

papacy went to a rival, Pope John VIII. And then

when Formosus found himself on the wrong side of

the issue of who should be crowned the new

emperor, he fled Rome. Pope

John VIII convened a synod and charged Formosus

with a laundry list of crimes under Church law. Among

the charges were deserting his diocese without

permission, opposing the crowning of the emperor,

and (quote) “conspiring with certain iniquitous

men and women for the destruction of the papal

see.” Formosus

was convicted, defrocked, and excommunicated. You might

think that would be the end of Formosus’s papal

ambitions, but you’d be wrong. Six years later,

the excommunication was lifted. In

return, Formosus promised never to return to Rome

or execute priestly duties. And for

a while, he didn’t. But then, in

882, Pope John VIII was clobbered over the head

with a hammer, thus becoming the first pope to be

assassinated.

Newly

installed Pope Marinus didn’t share his

predecessor’s grudge with Formosus. So he

released Formosus from his oath, and restored him

to his old diocese.

Three more

popes came and went—they seemed to drop dead with

alarming regularity around this time—until at

last, in 891, Formosus became the first former

ex-communicant to be elected Pope. But the job

came with a host of thorny problems. The most

important concerned the messy politics of the

Church and the Holy Roman Empire. The

previous pope had made a commitment to crown as

Roman emperor the very young Guy Spoleto III. But

Formosus had his own idea as to who should be

emperor. And so

Formosus persuaded one Arnulf of Carinthia to

invade Italy and liberate it from the control of

Emperor Spoleto.

Arnulf crossed the Alps and seized the city

of Rome by force in February 896. A day

later in St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Formosus

crowned Arnulf as the new emperor. Although

Spoleto died suddenly and was no longer in the

picture, nothing about what the Pope had done sat

well with his influential relatives. Two months

later, Pope Formosus died of a stroke, and for

eight months his corpse rested peacefully in its

vault at St. Peters.

But in January

897, power shifted again in Rome. Arnulf

suffered a stroke and left Rome. Once

again, Spoleto’s relatives were riding high—and

they hadn’t forgotten what Formosus did to them. They

didn’t mean to let a little thing like his death

get in the way of revenge. Spoleto’s

relatives put pressure on the new Pope, Stephen

VI, to put Formosus on trial for a list of alleged

crimes. It

might not have taken a lot of pressure. Stephen

VI and Formosus had been on opposite sides in

disputes involving Rome’s aristocracy. In any case,

Pope Stephen calls a meeting of bishops and

cardinals, the notorious Cadaver Synod. At this

meeting, it is decided to remove the rotting

corpse of Pope Formosus from its vault. Church

aides remove the shroud from the corpse, dress it

in pontifical vestments, put a crown on its skull,

and prop what’s left of Formosus up on a throne in

the Basilica of St. John Lateran. The

bishops and cardinals called as witnesses stare in

shock at the sight.

One can imagine them struggling to deal

with the overwhelming stench. Pope Stephen

appoints himself prosecutor. He also

appoints an 18-year-old deacon to serve as counsel

for Formosus.

What happens next is described by E. R.

Chamberlain in his entertaining book The Bad

Popes: “The council wisely kept silent while

Stephen raved and screamed his insults” at the

corpse. The charges

against Formosus include performing the functions

of a bishop after he promised not to, assuming the

papacy, and conspiring against a previous Pope. Among

the list of questions Pope Stephen has for the

corpse are: “Why did you usurp the universal Roman

see in such a spirit of ambition?” Why did

you exercise the office of bishop after you took

an oath to remain a layman? Why did

you commit perjury? Apparently,

dead Pope Formosus has no good answers for these

questions. So

Pope Stephen proposes that Formosus be found

guilty. The

bishops present don’t see any reason to disagree. They all

shout, “So be it!” Guards step

forward to carry out the sentence. The

three fingers of the corpse that Formosus once

used for blessings are hacked off. The

papal crown is removed and the papal garments

stripped off. A short while later, the body is

unceremoniously tossed into the Tiber River. Moreover,

bishops appointed by Formosus and still loyal to

him staged a Vatican coup. A mob

tossed Pope Stephen into a dungeon, where he was

strangled. Subsequently

the decrees of the Cadaver Synod were first

annulled and then reinstated by different popes.

Formosus’s corpse was first returned to its vault

and then exhumed and tossed into the Tiber again.

Eventually, however, Formosus’s bones found their

way back to St. Peter’s, where he was laid to rest

for a third—and one would hope final—time. The Cadaver

Synod succeeded in dampening enthusiasm for trying

corpses. Indeed, in 898 Pope John IX even issued a

decree prohibiting future trials of the dead. Even so, Pope

Formosus was not the last person to show up dead

for his trial. Over the next half millennium,

scores of other cadavers had their unwanted days

in court. So what was behind these trials? Why, in

the Middle Ages would one try a dead pope? Or

anyone else? In

part, such trials reflect medieval beliefs about

death—death is not the end; people move on to

their rewards and punishments in the next world. And a good

part of the interest in trying dead people can be

attributed to laws that allowed the confiscation

of property of persons convicted—dead or alive--of

serious crimes. As late as 1591, Judge Pierre

Ayrault argued in a treatise that convicting the

guilty after death made every bit as much sense as

posthumous exonerations of the innocent. Perhaps.

But is it really necessary for the dead defendant

to show up in court? The Trial

of Emma The Cadaver

Synod was something of a special case. What

about trials of non-popes, including ordinary

people, accused of committing ordinary crimes? In

these cases, most of Europe turned to systems of

justice that produced just results only if God

took enough interest in a case to provide it. Briefly put,

there were two techniques, each semi-rational at

best, that came into use. The

earliest trial form to develop was trial by

oath—or more precisely, trial by compurgation. In these

trials, a person accused of a crime tried to round

up people willing to swear to his or her

innocence—people called compurgators. The

number of oath-takers required to prove innocence

varied with the seriousness of the charge and

one’s place in society. These

trials were not fact-based inquiries; the oaths were the

evidence. Even

the high and mighty had to seek out compurgators. For

example, in 899 BC, Queen Uta of Germany stood

accused of adultery.

She won acquittal, however, when 82 knights

lined up to confirm her chastity. If that

seems like a high burden for Queen Uta, consider

that a person accused of poisoning in Dark Ages

Wales had to find 600 compurgators to prove his

innocence.  Queen Uta Trials by oath

made sense for people who believed God would

strike dead anyone who swore falsely. But

objections to the system—people understood perjury

was possible--led

to another form of trial process, trial by ordeal. At

first, ordeals were employed as a way of producing

a result in intractable cases, but its use spread

and in many places replaced compurgation

altogether. Let’s leave

Rome and travel to eleventh-century England for

the trial, if we can call it that, of Queen Emma

of Normandy.

But first a bit of background on “Trials by

Ordeal.” Trial by

Ordeal Trials by

Ordeal bear almost no resemblance to modern

trials. They

were proceedings designed to attract God’s

attention and have Him make the call: Guilty or

Innocent. If

a defendant was truly innocent, the thinking went,

God would step in and perform a miracle to save

the defendant from a grievous wrong. Trials

by ordeal were not, mind you, some wink-wink

proceeding. People of the medieval world, for the

most part, actually believed that

God would ensure a just outcome. For most

people of the time, God was ever-watchful—they

could scarcely imagine Him just sitting by and let

an innocent person be found guilty. In a trial by

ordeal the defendant was subjected to a challenge,

usually an unpleasant one causing serious injury.

A typical ordeal might involve walking over hot

irons or retrieving a stone from boiling water. The

defendant was found innocent if the injury

sufficiently healed within a specific time—3 days

was typical--and guilty if the injury still

festered. In

the more bizarre ordeal of the cold water, bound

suspects were thrown into a convenient body of

water to see whether they sank or floated. Because

water was believed to be pure and have the power

to repel sin, anyone who sank persuasively enough

was acquitted—and, with luck, might be

resuscitated and live to see another day.

No

contemporaneous records exist for the trial by

ordeal of Emma of Normandy. The

earliest surviving record comes from The

Annals of Winchester, written in about 1200.

As with any account written over a century after

the fact, it is best to assume the story as we

have it contains a mixture of fact and and a large

dose of fiction. According to

the Annals, the Archbishop of Canterbury

persuaded King Edward the Confessor to charge his

own mother, Emma of Normandy, with

adultery. The charge claimed that Emma had engaged

in sexual relations with Bishop Elfwine of

Winchester. Emma

insisted she was innocent—and that she willing

undergo the ordeal of hot iron to prove it. The Archbishop

of Canterbury agreed—but only with rigorous

conditions. (Quote):

“Let the ill-famed woman walk nine paces, with

bare feet, on nine red-hot ploughshares—four to

clear herself and five to clear the bishop. If she

falters, if she does not press one of the

ploughshares fully with her feet, if she is harmed

the one least bit, then let her be judged a

fornicator.”

Now that’s one tough test. So here’s the

scene. The nine red-hot ploughshares are laid

across the pavement in a church. Emma

enters and entreats God to save her. Led by

the hand by bishops, she starts to walk. Miraculously,

according to chroniclers, Emma passes the test

with flying colors.

According to one account, Emma “senses

nothing.” She

even turns to a bishop and asks, “When shall we

come to the ploughshares?” The bishops, no doubt

shocked by her question, tell her she just passed

over them. Her

feet are examined, or so the report goes, and they

are found to be uninjured. All

around proclaim a miracle. Emma is

innocent of the charge and free to go, with all

her confiscated property restored. There is

reason to take this account with a grain of salt. Perhaps

the ploughshares were not as hot as the archbishop

ordered, perhaps Emma’s feet were toasted, but

less so than expected. Perhaps

the ordeal never even occurred at all. Separating

fact from fiction can be difficult in a period

without much record-keeping. It is

beyond question, however, that the ordeal of hot

iron was one of the more common forms of ordeal

during this time period. Note also the

involvement of the Church in these trials. The

Catholic Church took to trials with gusto. The use

of ordeals actually expanded

in

the ninth through eleventh centuries along as

Latin Christendom spread in Europe. The Church

found trials by ordeal to be a handy way of

dealing with heretics. “Want to

prove you are a good Catholic?—take the ordeal of

the hot irons!”

The Church realized another benefit from

the system. Priests frequently were paid to

supervise ordeals. If chroniclers

are to be believed, trials by ordeal had a fairly

high exoneration rate. Priests had a great deal of

latitude to make judgments, even assuming the

ordeals themselves were not manipulated, as of

course they could be. Has the wound healed enough

to prove innocence?

That can be a question without a clear

answer. Perhaps a bribe might influence the final

call? Given the discretion here, woe to the poor

defendant undergoing an ordeal who had crossed the

priest in some way. Meanwhile

in Iceland: The Burnt Njal Trial (circa 1012) Isolated

from the rest of Europe, Iceland developed a

unique culture and legal system. One of

the treasures we have from the medieval world

are Icelandic sagas. And the greatest of

all Icelandic sagas, The Saga of Burnt

Njal (written in about 1280), tells of a

remarkable trial that took place at Iceland's

Law Rock in about 1012. (Of course,

given time between the trial and when the

story was put into writing, again one must

assume the account is a mix of fact and

fiction.)The trial grew out of a long-lasting

feud of monumental proportions. One

group of feuders, led by a chieftan named

Flosi with a hundred men, descend on the

farmhouse of one of the key feuders on the

other side, Njal. With

Njal and his son inside, trying as best they

can to mount a defense, the house in set on

fire. All

inside die except for Njal’s nephew, Kari

Solmundarson, who climbs to the rafters and

leaps from the roof with his hair and clothes

ablaze. Kari

plunges into a nearby stream, but is left

disfigured and in pain from severe burns. Kari’s

mission becomes seeking revenge for the deaths

of Njal and his other relatives. Law Rock in southwestern Iceland

Feuds can be destructive

of society.

At the turn of the millennium,

religious and secular authorities in Iceland

hoped that a legal system might break, or at

least slow, the tide of violence. When

Kari spreads the news of the awful fire, he

gets surprising advice from a foster son of

Njal, Thorhall Asgrimsson. He

tells Kari they should take the murderers to

court. When Flosi receives

notice of the suit, he considers settlement,

but is persuaded by another member of the gang

of arsonists that they should instead hire

their own lawyer. Flosi

visits Eyjolf Bolverksson, the most

highly-regarded lawyer in all of Iceland, and

asks him if he will take their case. Eyjolf,

described in the saga as bedecked in a scarlet

cloak and gold headband, initially turns down

Flosi’s request.

But Flosi’s offer of a splendid gold

chain for his services causes him to

reconsider.

He tells Flosi that he will take the

case. At

the time, however, accepting compensation for

legal services was considered improper—so one

could guess where the saga might be going. Eyjolf

will come to regret his decision to defend

Flosi and his gang. Trials in Iceland took

place at Law Rock, a beautiful spot between a

lava cliff and a wide valley sliced by a

shining river.

On the actual rock, once each summer,

the Law Speaker recites to everyone present

one-third of Iceland’s legal code. (The

next summer, he will recite a different third

of the code, and in the third year, he will

complete his recital before starting over

again the next year.) When

a case was to be heard, lawyers would gather

in their respective booths, while around them

circulated jurors and interested spectators. In Kari’s trial, Kari’s

nine jurors seated themselves on the ground. They

are present not to weigh facts, but rather to

swear that Kari followed proper legal

procedures in bringing his suit. All

become silent when Kari’s lawyer, Mord

Valgardsson, stepped up to Law Rock. In

what we might call his “opening statement,”

Mord announced that he will plead truly,

fairly, and in accordance with the law. He

then asked witnesses to swear he had been

lawfully appointed and that the defendants had

been given notice of the suit. He

then asked if anyone had any objections. Eyjolf Bolverksson was

ready. He

argued that two of the jurors should be

disqualified on the ground they are related to

him. Mord

had no answer to the objection and the suit

seemed on the verge of dissolving. But

one man might have the answer: Thorhall

Asgrimsson.

Thorhall, to his great consternation,

could not attend the court proceedings because

of an ugly leg inflammation that had left him

bedridden.

Messengers rushed to

Thorhall’s home, got his legal advice, and

then passed it on to Mord. Mord

stood to refute Eyjolf’s argument for

disqualification. He

said that only kinship with the accuser, not

with a defense attorney, required a juror to

step down.

Sadskat Kadri, in his

lively account of the trial, notes that all

around considered Mord’s response “brilliant,”

but that Eyjolf “pulled another arrow from his

quiver.” Eyjolf argues that home ownership is

a requirement for jurors, but that two of

Kari’s jurors are not homeowners. Once

again, messengers ride off to Thorhall and

come back with his rejoinder: ownership of a

cow is sufficient to establish eligibility to

serve as a juror. This

claim turned out to be a matter of dispute,

and so the question is put to the Law Speaker,

Skapti Thoroddsson. He

emerged from his booth to announce his

decision.

A cow, indeed, will do. Eyjolf has one last

trick up his sleeve. Jurors,

in Iceland, are the men living closest to the

scene of the crime. (Note

that in Medieval Iceland, the legal system

expected jurors to be the people most knowledgeable

about a crime, not—as seems the preference in

our system—people with almost zero knowledge

of the crime.)

Eyjolf argued for disqualification of

four jurors who, he said, lived more distant

to the scene of the crime that others not

asked to serve as jurors. Yet again Mord had an

answer. He

said cases could be decided by a majority of

the nine jurors, and five still remain. The

Law Speaker seemed stunned. He

believed he was the only person in all of

Iceland who knew this fine legal point,

but—yes—five jurors would suffice. With issues of juror

eligibility finally behind him, Eyjolf

proceeded to his next argument, a

jurisdictional claim. He

argued that the case had been brought before

the wrong division of the Law Rock. This

turned out to be true, but resulted in only a

short delay as Kari’s team refiled the case. The

prosecution (that is, Kari’s side) now took to

offense, contending that Eyjolf was guilty of

bribery for accepting the gold bracelet as

payment for his services. But

what could have been a knockout blow became

irrelevant in light of a serious legal error

by Mord.

Mord demanded that six of the 36 judges

in the case stand down and that the remaining

judges award Kari’s side the verdict. But

for reasons that only the best scholar of

Medieval Icelandic jurisprudence might fathom,

this was a mistake. Mord

should have asked to remove twelve judges, not

six. The

legal blunder meant that Kari and the other of

Njal’s kinsmen, far from winning their case,

faced exile!  Kari Solmundarson Even Thorhall had no

remedy for this problem. Instead,

he roused himself from his bed and, blood

pouring down his leg, made way for Law Rock. Thorhall,

despite being an admired jurist, evidently had

had it with legal maneuverings. When

he encountered Grim the Red, a member of

Flosi’s legal team, he plants a spear into the

man, splitting his shoulder blades in two. Then

all hell broke loose. The

fact that such a gravely injured man as

Thorhall was moved to action inspired other

members of Kari’s side to fight. Soon,

as Kadri describes it, “Across the Law Rock,

weapons fly, bones crack, body parts are

pierced, and at least one bystander is hurled

headlong into a boiling cauldron.” When

the Law Speaker proposed a cease-fire

negotiation, his answer was a spear through

both his calves.

The action reached its climax when

Eyjolf Bolverksson was spotted by one of

Kari’s supporters. “Reward

him for that bracelet,” the friend suggested

to Kari.

Kari launches a spear that cuts clean

through the pleader’s waist. The next morning, after

the dead were buried and wounds bound, some of

the trial participants returned to Law Rock. It

was for one of Flosi’s team to state the

obvious: “There have been harsh happenings

here, in loss of life and lawsuits.” Trial by

Combat: "The Last Duel"  One variation

of ordeal still captures our imagination. You

know it. It’s

a form of ordeal played out on 21st-century

fairgrounds by re-enactors in medieval

festivals: Trial by Combat. Two

things distinguish Trial by Combat from all the

other varieties of ordeal used in the Middle

Ages. First,

most ordeals were unilateral, involving one

party only.

It takes two to duel. Second,

for a defendant in most forms of ordeal to prove

innocence, he or she had to hope that natural

processes worked in a surprising way. Not so

with Trial by Combat, where skill and cunning

could make all the difference.

The last great

example of trial by combat took place in 1386, at

an abbey north of Paris, where royalty, dukes, and

thousands of ordinary Parisians gathered to watch

the bloody spectacle. To say that

the two combatants, Jean de Carrouges and Jacques

Le Gris, had a history is a bit of an

understatement.

At one time, the two were close friends. So

close, in fact, that Carrouges chose Le Gris to be

the godfather of his first son. But

things began to deteriorate. When

both men were in the court circle of Count Pierre

d’ Alençon,

Le Gris became the Count’s favorite vassal. The

Count rewarded Le Gris with a prized estate and

other favors.

Carrouges became jealous and the two became

rivals. Carrouges fell

in love and married the daughter of a Norman lord. His new

bride, Marquerite, was a pretty good catch. She is

described as “young, beautiful, good, sensible,

and modest.”

It also turns out that Marquerite’s father

used to own a valuable estate, which he had sold

to Count Pierre three years before his daughter’s

marriage. Pierre,

in turn, handed the sought-after estate to

Carrouges’ archrival, Le Gris. So Carrouges

launched a lawsuit against Le Gris. He

alleged that the transfer of the estate to Count

Pierre was null and void for reasons that need not

occupy us here.

The bottom line is, Carrouges argued

the

land in question still really belonged to his

in-laws. But the lawsuit went nowhere. But in 1384,

Carrouges and Le Gris had a chance meeting at a

party and apparently agreed to bury the hatchet. Carrouges

even introduced Le Gris to his beautiful wife

Marquerite. Big mistake. Marguerite

answers a knock on the door. The door

knocker is a man-at-arms named Adam Louvel. Louvel

questions her about a loan for a minute. Then he

announces--surprise!--Jacques Le Gris is waiting

outside and he really

would like to see you. Marguerite

declines

the offer. Louvel

persists: “He loves you passionately, he’ll do

anything for you.

He really, really wants to see you.” Marguerite

still says no.

Le Gris barges in anyway. Then,

according to Marguerite, he propositions her. He

sweetens the offer by throwing in a goodly sum of

money if they can just have sex and keep mum about

it. Again,

Marguerite says no.

Le Gris, with Louvel helping, proceeds to

rape Marguerite.

Before he leaves, Le Gris threatens to kill

Marguerite if she tells anyone, including her

husband, about what just happened. Carrouges

returned several days later, and despite Le Gris’

threat, Marguerite could not keep silent. She

tearfully told her husband that Le Gris raped her.

We can assume that when Carrouges heard this news

he became fighting mad. Worse yet,

Marguerite told her husband that she was

pregnant--and could not know who the father was. Carrouges

decided to press charges of rape against Le Gris. But the

suit had a problem.

First, there was the “he said-she said”

aspect of it. Marguerite was the only witness. Le

Gris would surely deny the rape. Second,

the judge for the case would be none other than

Count Pierre.

The Count was assigned the duty of resolving

disputes involving his vassals. And

we can guess whose side HE would take. In fact, the

deck was stacked so steeply against them that

Carrouges and Marguerite didn’t even bother to

attend the proceeding. Predictably,

the Count acquitted Le Gris of all charges and

proceeded to accuse Marguerite of “dreaming” the

attack. But the

Count’s verdict could be appealed to Court

Pierre's overlord, King Charles VI. Guessing

that a traditional appeal would fail, Carrouges

came up with another plan. A plan

that might prove attractive to the King and his

Court’s lust for entertainment. Carrouge

proposed that the rape charge be settled through

trial-by-combat. Trials by

combat had once been a common means of resolving

disputes in France.

But by 1386 they had become very rare. A 1306

law limited trials by combat to only capital

crimes involving noblemen. Carrouges probably

expected his idea to be rejected. But the

French court was intrigued. A good

old-fashioned trial-by-combat might be fun. In the second

phase of legal process, Carrouges and Le Gris and

their respective supporters showed up at the

Palace of Justice to issue a formal challenge.

Before the King's Court (The Parlement of Paris, a

body of 32 magistrates), they each recited their

accusations.

Carrouges accused Le Gris of rape. Le Gris

accused Carrouges of defamation. Then

they each threw down the gauntlet. Literally. Throwing

down a gauntlet was the formal indication of each

man’s willingness to fight. Interestingly,

the King's Court decided to hold off on the

judicial duel and to hear the case as an ordinary

criminal one first.

The criminal trial dragged on through much

of the summer.

But, finally,

the King's Court handed down its verdict--or

non-verdict.

The magistrates announced they could not

reach a decision.

A judicial duel to the death it would have

to be. When you hear

the word “duel,” you might think of something like

the Hamilton-Burr duel. A couple

of men, deciding for their own foolish reasons, to

settle scores in an old-fashioned and violent way. But this

is a judicial duel, a form of ordeal that assumes

God will be watching over and directing the

outcome. In

this judicial duel, not only would the survivor

survive, he would be in the eyes of God, and the

law, vindicated.

Now, it wasn’t

just the lives of the two men that hung in the

balance. Marguerite’s life did as well. For if

her husband died, that could only mean that her

rape accusation was baseless and that she had

committed perjury.

Perjury was a capital offense. So,

Marguerite knew that if her husband lost the duel,

she would be immediately burnt at the stake. If ever

a wife had reason to cheer her husband on in

battle, here it was. And so the big

day arrives: December 29, 1386. Thousands

of spectators begin gathering at dawn, hours

before the event. They flock to a jousting arena

at an abbey in the north Paris suburbs. The king

is there too, as well as an impressive collection

of dukes. Marguerite,

dressed in black, sits in a carriage overlooking

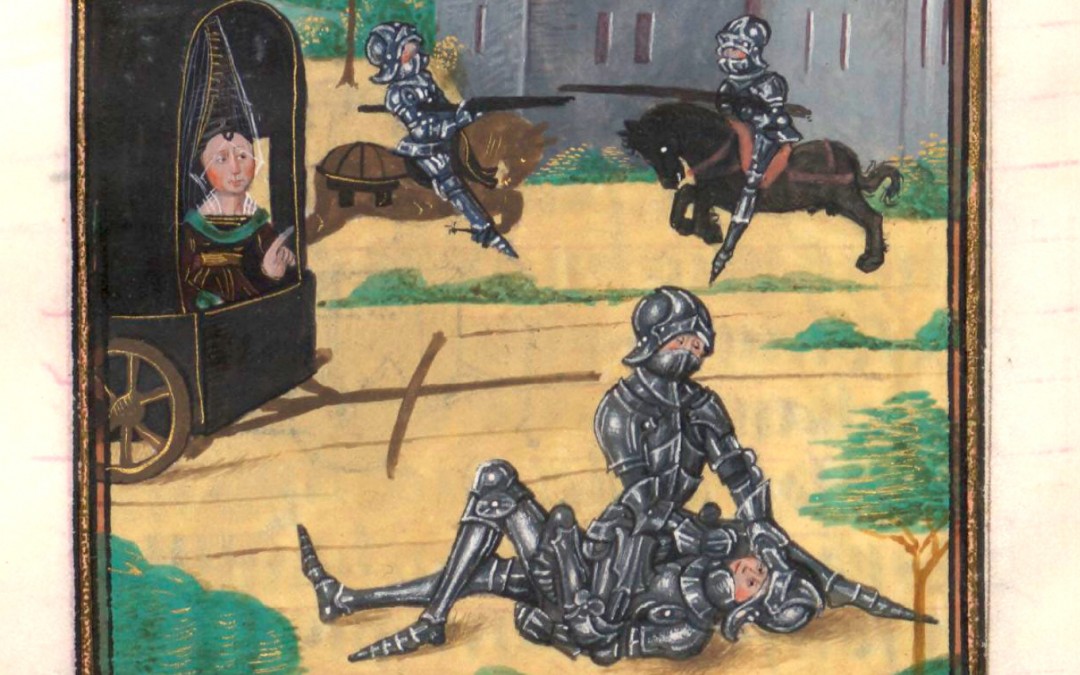

the field.  Marguerite says goodbye to Carrouges moments before his duel with Le Gris (British Library) The two

combatants, dressed in full armor and each riding

a horse, take the field. Each man

has an impressive collection of weapons. They

each carry a lance, a sword, a long dagger, and a

heavy battle axe.

Carrouges recites to the crowd his charges

against Le Gris.

Then its Le Gris’s turn, and he recites his

charge of defamation. They

each dismount their horses and give oaths to God

and the Virgin Mary and St. George. The

oaths, a key part of the process, ensure God’s

judgment--and not just their own jousting

skills--will determine the outcome of the duel. The King’s

instructions are read. Essentially

the deal is this: anyone who runs onto the field

and interferes with the duel will be executed and

anyone who interferes with the duel by shouting

will have their hand cut off. Effective

crowd control measures, no doubt. Then

it’s show time. The horses

square up at the proper distance. The

marshal signals.

The two men charge at each other. On the

first pass, their lances strike, but no harm is

done. On

the second pass, they strike each other on their

armored headpieces.

They wheel around and charge at each other

a third time, striking each other’s shields and

shattering both lances. The axes

come out in in round four. They

slash at each other with axes until Le Gris

manages to drive his through the neck of

Carrouges’s horse, beheading it. The poor

horse stumbles to the ground and Carrouges jumps

off. He

charges at Le Gris’s horse and disembowels it. (You

have to feel for the innocent horses, if not the

combatants.) It’s time to

pull out the swords and battle on foot. The two

men thrust and parry and all those other things

you do with swords.

This goes on for several minutes. Le Gris

gains the advantage after he manages to stab his

rival in his right thigh. But

Carrouges isn’t finished yet. He

wrestles Le Gris flat to the ground, not a very

good place to be if you’re wearing very heavy

armor. Carrouges

stabs his rival right and left, but he not getting

anywhere--the armor is just too tough for the

sword. So

he tears Le Gris’s faceplate off and shouts at his

old nemesis.

Admit your guilt, you fiend. Le Gris

cries out, “In the name of God and on the peril of

damnation of my soul, I am innocent!” That

does it. Carrouges

takes out his dagger and drives it through Le

Gris’s neck, killing him. Marguerite,

watching all this, is quite relieved. But

before the victor can receive congratulations from

his wife, he is bandaged up by his pages and walks

over to the King.

He kneels before the King and accepts his

prize of a thousand francs. Carrouges

limps off to bow and clasp his wife as the crowd

shouts its approval.

Finally, the happy twosome ride from the

jousting field to the Cathedral of Notre-Dame to

thank God for securing them justice. With that, the

curtain comes down on trial by combat in France. Never

again would the French government sanction a

judicial duel. Each of the

trials we’ve examined in this lecture was

exceptional.

The Cadaver Synod exceptional in its

grotesqueness, the trial by ordeal of Emma of

Normandy exceptional for its reported outcome and

the high status of the accused, and the trial by

combat exceptional for what it represents, the

last great example from a system of deciding cases

based on the assumption that God cares enough

about the outcome to produce a just result. Each

trial appears crazy to the modern mind, but the

mindsets of the men and women of the medieval age

were decidedly not modern. They

believed in a God who perpetually watched and

tinkered with his creation. The End of

an Age Even as early

as the ninth century, trials by ordeal had its

critics. Skeptics

questioned whether God actually had much interest

in stepping in to make sure every ordeal came out

as it should. Charlemagne must have noted the

criticism when he commanded, “Let all believe in

the ordeal without doubting.” As

historian Robert Bartlett observed, the

commandment would scarcely have been necessary if

there were no doubters. By the late 12th

century, criticism of ordeals grew louder. Couldn’t

God secure justice if He wanted without

ordeals—aren’t they just superfluous? Isn’t it

presumptuous to assume we can determine God’s will

from a test we make up? Might

not a guilty person use magic and falsely win his

innocence? Isn’t it possible God might simply

choose to sit an ordeal out, and not intervene? If

someone who is guilty confesses, shouldn’t that

cleanse their guilt and result in the ordeal

showing them to be innocent? What if 3 suspects

are made in turn to walk over hot irons—doesn’t

the third and last suspect to do the walk have a

better chance of being found innocent? And

where in the Bible, exactly, is support for this

whole notion of ordeals? These critical

voices began to be heard at the highest levels. In 1199,

Pope Innocent III approved a new way of proceeding

in criminal cases: judges on their own motion

could launch inquiries into crimes, even look into

the minds of the accused. The new

proceeding was called “the inquisition.” Sixteen

years later, in 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council

prohibited priests from blessing ordeals by fire

or water. The

age of the trial by ordeal was closing. |