×

|

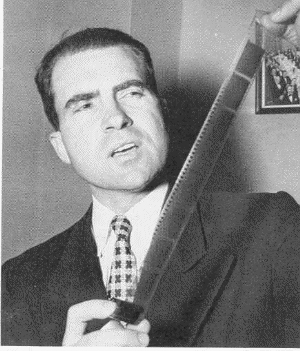

President #1: Richard M.

Nixon

On August 7, Nixon's subcommittee met Chambers at the Federal Court House in New York City to pursue its investigation into the confessed spy's association with Alger Hiss. Nixon asked many questions designed to determine whether he knew the things about Hiss that he should "if he knew him...as well as he claimed." Chambers had most of the answers on such subjects as nicknames, habits, pets, vacations, mannerisms, and descriptions of floor plans and furniture. On the question of whether Hiss had any hobbies, Chambers gave an answer that would soon haunt Hiss: Yes, he did. They both [Alger and Priscilla Hiss] had the same hobby--amateur ornithologists, bird observers. They used to get up early in the morning and go to Glen Echo, out the canal, to observe birds. I recall once they saw, to their great excitement, a prothonotary warbler.Hiss faced more hostile questioning from the Committee in executive session on August 16. Stripling pointedly observed that either Chambers has "made a study of your life in great detail or he knows you." After being shown two photographs of Chambers, Chairman Thomas asked Hiss whether he still maintained that he did not recognize the man who claimed to have spent a week in his house. Hiss answered, "I do not recognize him from that picture...I want to hear the man's voice." After a morning recess, Hiss announced that he now believed that his accuser might be a man he knew in the mid-1930s as "George Crosley," a free-lance writer who he said sought out information about Hiss's work on a congressional committee dealing with the munitions industry. Crosley's most memorable feature, according to Hiss, was "very bad teeth." A turning point in the investigation came when Richard Nixon

asked,

"What hobby, if any do you have, Mr. Hiss?" Hiss answered that

his

hobbies were "tennis and amateur ornithology." Congressman John

McDowell

jumped in: "Did you ever see a prothonotary

warbler?" Hiss fell into the trap, responding, "I have--right

here on the Potomac. Do you know that place?" In

discussions

after the hearing, Committee members indicated they were now convinced

Hiss was lying, based in large part on the response about the

warbler.

It seemed to Stripling and others very unlikely that Chambers could

have

known about such a detail through a general study of Hiss's life.

It had to be firsthand knowledge..... The Hiss case set in a motion a chain of events that would forever change American politics. Joseph McCarthy, a little known senator form Wisconsin, seized on the Hiss conviction to charge that the Department of State was "thoroughly infested" with Communists. Soon he would begin divisive hearings--the controversial "witch-hunt." (Chambers disassociated himself with McCathy's crusade, saying "For the Right to tie itself in any way to Senator McCarthy is suicide. He is a raven of disaster.") Richard Nixon's sudden fame from his role in the Hiss-Chambers attention led the 1952 Republican nominee for President, General Dwight Eisenhower, to select him as his running mate. Most significantly, Chambers fanned the anti-Communist embers that within a decade evolved into a grassroots conservative movement in the Republican Party that, in 1964, produced the nomination of Barry Goldwater and, in 1980, the election of Ronald Reagan. It is often forgotten what Lionell Trilling observed about political thought in America before the Hiss case: "in the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition." President #2: Ronald Reagan

|