|

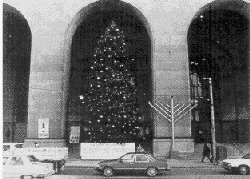

Like many other perplexing constitutional issues, the issue of what religious symbols may occupy various public spaces is essentially a where-to-draw-the-line question. Only absolutists would find objectionable a religious painting in the National Gallery of Art, and only absolutists would see no problem with the placement of a giant crucifix on top of the Capitol Building. A line will have to be drawn, and the differences between a constitutionally permissible religious display that is close to the line and a constitutionally impermissible display that is also close to the line may seem laughably small--or even silly. Welcome to "the-two-plastic-animals rule." Lynch (1984) and County of Allegheny (1989) both concern the placement of nativity scenes on public property during the Christmas season. In Lynch, the Supreme Court uses the three-prong Lemon test to conclude that a creche in Pawtucket, Rhode Island does not violate the Establishment Clause. Five years later, the Court uses the same test in Allegheny to conclude that a creche in a county building violates the Establishment Clause. The distinguishing feature, Justices Blackmun and O'Connor suggest, is that the Pawtucket display included secular Christmas symbols such as a Santa Claus and--yes--two plastic animals (reindeer and elephants). The presence of the secular symbols made the overall effect of the display more a celebration of a season than an endorsement of religion. By contrast, Allegheny County's display featured only a creche surrounded by poinsettias-- and no secular symbols. (The Court in Allegheny upholds the constitutionality of a menorah, also set on public property in Pittsburgh, in part because it is dwarfed by a nearby 45-foot Christmas tree, minimizing the likelihood that the menorah could be taken as a sign of government endorsement of Judaism.) [See photos of the two displays involved in Allegheny below:]

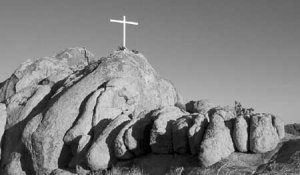

In 1995, in Capitol Square Review Board, the Court considered whether a free-standing cross, placed by the KKK in a public square across from the Ohio State Capitol building, would violate the Establishment Clause. Concluding that the space in question was a public forum (a space traditionally used for, or set aside for, expressive activity), the Court ruled that private placement of the cross would not constitute an endorsement of religion. Writing for four members of the Court, Justice Scalia insisted that the test was not whether a reasonable person might perceive the cross to be an endorsement of Christianity by Ohio. Scalia said the real issue is whether Ohio promoted religion, and promotion is not--he concluded-- to be found when a private organization is allowed to use a public forum for religious expression on the equal terms with other organizations.

In 2019, the Court signaled both a new approach to these cases and a new willingness to tolerate religious symbols on public land. In American Legion v American Humanist Association, the Court reversed a lower court decision to order the removal of a 32-foot tall Latin cross installed on public land in 1925 to honor WW I veterans who had died during that war. Writing for the Court, Justice Alito offered reasons for refusing to apply the Lemon test and instead recognizing a presumption of constitutionality in the case:

If the Lemon

Court thought that its test would provide a

framework for all future Establishment Clause

decisions, its expectation has

not been met. In many cases, this Court has either

expressly declined to apply

the test or has simply ignored it. This pattern is a

testament to the Lemon test’s

shortcomings. As Establishment Clause cases

involving a great array of laws and

practices came to the Court, it became more and

more apparent that the Lemon

test could not resolve them. It could not “explain

the Establishment Clause’s

tolerance, for example, of the prayers that open

legislative meetings, . . .

certain references to, and invocations of, the

Deity in the public words of

public officials; the public references to God on

coins, decrees, and

buildings; or the attention paid to the religious

objectives of certain

holidays, including Thanksgiving.” The test has

been harshly criticized by

Members of this Court, lamented by lower court

judges, and questioned by a

diverse roster of scholars. For at least four reasons, the Lemon test presents particularly daunting problems in cases, including the one now before us, that involve the use, for ceremonial, celebratory, or commemorative purposes, of words or symbols with religious associations. Together, these considerations counsel against efforts to evaluate such cases under Lemon and toward application of a presumption of constitutionality for longstanding monuments, symbols, and practices.

|

Lynch v Donnelly (1984) County of Allegheny v ACLU (1989) Capitol Square Review Bd. v Pinette (1995) Van Orden v Perry (2005) American Legion v American Humanist Assn (2019)

Complaint

&

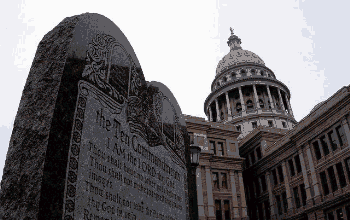

Answer Questions 2. Since 1989 when Allegheny County was decided, three new justices have joined the Court: Thomas, Ginsburg, and Breyer (replacing White, Marshall, and Brennan). With the Court's current composition, do you agree that Allegheny County would be likely to come out the same way today, with Thomas replacing White in dissent? Do the views of Ginsburg and Breyer in Capitol Square offer any clues as to how they would approach the case? 3. Why do Allegheny's poinsettias not save its creche the way the talking wishing well and plastic reindeer did for Pawtucket? How does a judge decide what "adds to" and what "detracts from" a possible message of endorsement? 4. If Allegheny County's menorah stood next to an 8-foot Christmas tree would it have withstood constitutional challenge? Does the display (see picture at right) suggest to you a "salute to religious liberty"? Would the salute be clearer if Allegheny County added a giant Buddha such as the Taliban blew up in Afghanistan? 5. Taken together, Lynch and Allegheny County suggest a Court obsessed with trivial matters such as the presence or absence of plastic animals, but can you suggest a better line to draw? 6. Should Allegheny County come out differently if the county put a large sign next to the creche: "The County does not intend by this display to suggest any endorsement of Christianity"? 7. Is a December music program in a public school constitutional if all the songs are religious and pertain to Christmas? Is the program saved by adding "Frosty the Snowman"? 8. What message was the KKK trying to send by displaying its cross in Capitol Square? Do you see the case as raising Establishment Clause issues? 9. Analyze the constitutionality of the Republic, Missouri seal and the Ten Commandments plaque on the County Courthouse in Pittsburgh (see picture and photos above). Links

|