|

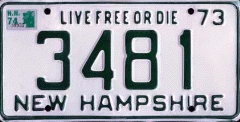

In 1977, the Court considered another compelled speech claim, this one brought by a New Hampshire couple who had three times been prosecuted for covering up the motto "Live Free or Die" on their New Hampshire license plate. The Maynards, also Jehovah's Witnesses, objected on religious grounds to the ideological message conveyed on the state license plates. Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Burger enjoined enforcement against the Maynards of New Hampshire's law prohibiting the obscuring or defacing of license plates. The law, the Court said, compelled individuals to be "couriers for ideological messages" and "mobile billboards." In

1980, in Pruneyard Shopping Center vs Robins,

the Supreme Court rejected the argument of the

owner of a California Shopping Center that a

California Supreme Court decision finding a state

constitutional right of third persons (in this

case, high school students) to pass out political

leaflets on the shopping center grounds violated

the federal Constitution's First Amendment.

The owner argued, relying on Wooley and Barnette,

that his property was being used in such a way as

to suggest his endorsement of a political message

that he may not have agreed with. The Court

disagreed, concluding under the circumstances of

the case that no one was likely to conclude that

the shopping center was a sponsor or an endorser

of the political message being presented in the

shopping center parking lot. In

2006, in Rumsfield

v Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights,

the Supreme Court considered the claim of various

law schools that the Solomon Amendment, which

withheld federal funds for schools discriminating

against military recruiters, violated their First

Amendment rights. The schools argued, among

other things, that the law compelled them to

support speech (i.e., military recruiting on their

premises that was inconsistent with their belief

that employers should not discriminate against

homosexuals) with which they disagreed. In a

unanimous (8 to 0) decision, the Court rejected

the schools' arguments. Justice Roberts

noted that the law doesn't make the schools say

anything (and in fact allows them to disassociate

themselves from the military recruiters' message

by organizing protests or boycotts) and regulates

conduct more than it does speech. The

Court extended the compelled speech doctrine in

the important 2018 case of Janus v American

Federation of State, Local,

and Municipal Employees. In a 5 to 4

decision, the Court overrule a precedent case from

1977 that held that public employee unions could

require employees who chose not to join the union

to make a financial contribution (less than the

normal union dues) to cover the cost of the union

representing the employee in collective

bargaining. The fee was said to be justified

as a measure designed to keep union peace and

avoid the "free-rider" problem of employees

getting the benefit of union negotiations without

paying for any of the cost. Writing for the

Court in Janus, Justice Alito said that

forcing employees to subsidize speech (union

positions regarding negotiation and what state

fiscal policy with respect to employees should be)

is a form of compelled speech. The Court

held that neither of the main justifications for

the fees were sufficiently compelling to support

the policy. Unions worried that the effects

of Janus will be very harmful to the union

movement. In 2023, the Court, in 303 Creative v Elenis, considered whether the State of Colorado could compel a web designer to design websites for gay marriages, even though such marriages were inconsistent with her own deeply held religious beliefs. The Court, in an opinion by Justice Gorsuch, held that the First Amendment's compelled speech doctrine prohibited enforcement of Colorado's anti-discrimination laws under the facts of the case. The Court described website designing as clearly expressive speech triggering the need for Colorado to show a compelling state interest for enforcement of its law. the Court said that the claimed interest in preventing discrimination against a protected class was insufficient, given the many alternative website designers ready and willing to design websites for gay marriages. The Court also noted that the website designer was not discriminating based on the status of a customer (She claimed happy to serve gay customers, just not willing to use her artistic efforts in support of a ceremony she found immoral).

|

Marie and Gathie Barnette, two of the petitioners in West Virgina v Barnette, a challenge to a West Virginia law requiring school children to salute the American flag. The

Cases

Mark Janus is cheered by supporters near the steps of the Supreme Court Questions 2. How significant would you rate the government's interest in forcing school children to salute the flag? 3. What do you think of Justice Frankfurter's dissent in Barnette, arguing that the Court should only determine whether the State had a reasonable justification for its requirement? 4. Is anyone likely to take the Maynards' showing of an unobstructed "Live Free or Die" motto as an indication that they endorse that message? 5. Couldn't the Maynards disavow the objectionable motto by placing an "I-Don't-Believe-the-Message-Below" sign above the license plate? 6. If an Idaho citizen found the Idaho license plate motto "Famous Potatoes" to be silly, would he or she have a constitutional right to cover the motto, or does the right recognized in Wooley extend only to mottos found to be ideologically objectionable? 7. Would Pruneyard have been decided differently if California had compelled the owner of a stand-alone store to allow political leafletters to use his or her property? 8. Is the state's interest in allowing private citizens to use shopping centers for political expression considerably stronger than the state interest in Wooley, promoting a state motto on license plates? 9. In 1999, Louisiana enacted a law that allowed state residents to buy a license plate with the message "Choose Life" (see photo). Abortion rights organizations challenged the law on First Amendment grounds. The issues raised by the Louisiana case are very different than those presented in Wooley. Does the Louisiana "Choose Life" plate violate the First Amendment? (In July, 2003, a federal district judge ruled that Louisiana's system of speciality plates violated the First Amendment because it allows the anti-abortion plates but does not provide one for the opposite viewpoint.) 10. If the Solomon forbid law schools--upon pain of losing federal funding--from in any way protesting the presence on their campuses of military recruiters, would the law then violate the schools' First Amendment rights? |