|

Buckley considered the constitutionality of a federal campaign financing law that imposed numerous restrictions on both candidate's own spending and the contributions of individuals to campaigns. The challenge to the act was brought by unlikely political bedfellows, including conservative Senator James Buckley and liberal anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy. The

Court in Buckley upheld some of the

provisions of the act, while striking down

others. In particular, the Court invalidated

limits placed on the personal expenditures of

candidates for federal office, thus paving the way

for runs by wealthy candidates such as Ross Perot

in 1992. The Court also struck down a $1000

limit on individual spending on behalf of a

campaign, concluding that the restriction

was not closely tailored to serving the

government's asserted interest in preventing

corruption. On the other hand, the Court upheld

limits on individual contributions to

campaigns and the use of federal matching funds

for candidates who agree to abide by federal

spending limits. The Court also upheld donor

disclosure requirements, except as they apply to

controversial third parties where disclosure might

prove embarrassing to donors. Citizens

Against Rent Control (1981) considered

the legality of a Berkeley, California ordinance

limiting contributions to campaigns to support or

oppose ballot measures to $250. The Court

invalidated the limitation, concluding that the

concern in Buckley about "buying influence" had

little applicability in the case of ballot

measures. In reaching its conclusion, the

Court seemed either to be applying strict

scrutiny--or something very close to it. In

2007, the Court signalled a new willingness to

strike down campaign finance regulations. In

Federal Election

Commission v Wisconsin Right to Life, the

Court voted 5 to 4 to invalidate a key section of

the McCain-Feingold Act that banned corporations

and unions from buying broadcast ads that mention

the names of candidates for federal office in the

weeks immediately before an election.

In

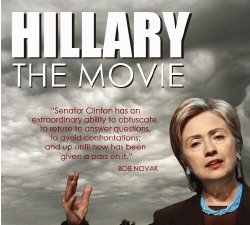

2010, the Supreme Court considered whether the

First Amendment allowed the government to impose

limits on direct funding of political attacks by a

corporation. Citizens United v Federal Election

Commission involved a challenge to a

corporately-funded documentary attacking the

candidacy of Hillary Clinton. Voting 5 to 4,

the Court ruled that the First Amendment

prohibited the government from banning political

spending by corportations (and, presumably, labor

unions) in candidate elections. Writing for

the Court, Justice Kennedy wrote “If the First

Amendment has any force, it prohibits Congress

from fining or jailing citizens, or associations

of citizens, for simply engaging in political

speech.” The decision

overruled earlier Court decisions (Austin, and

portions of

McConnell) that suggested

limitations on corporate speech in campaigns serve

the compelling interest of in eliminating the

distorting effects on a campaign of immense

aggregations of wealth. The Court also

rejected the argument that the law served the

compelling goal of reducing political corruption.

Justice Stevens, in dissent, called the majority

decision "a rejection of the common sense of the

American people." The Court affirmed

F.E.C. rules requiring disclosure of the name of

the sponsor of the political message. The

case did not consider the constitutionality of the

limitation on corporate donations directly to the

campaign of a candidate for federal office.

The Citizens

United decision was attacked by President

Obama in his 2010 State of the Union Speech, and

Democrats in Congress proposed new regulation to

limit the effect of a ruling that they believe

clearly favors Republicans, who are likely to

receive disproportional corporate support in

election campaigns. In the

2014 case of McCutcheon v Federal Election

Commission, the Court, 5 to 4, struck down a

provision in the 2002 Campaign Reform Act that

limited how much an individual could contribute

during an election cycle to all candidates and

campaign committees. Writing for the Court,

Chief Justice Roberts concluded that the aggregate

limits dis not further the government's legitimate

interest in preventing corruption or the

appearance of corruption, nor was the provision

closely drafted to not unnecessarily trample on

protected associational freedoms protected by the

First Amendment. The four Democratic

appointees to the Court all dissented, with

Justice Breyer arguing that the decision, coupled

with the Citizens United ruling,

"eviscerates our Nation's campaign finance laws,

leaving a remnant incapable of dealing with the

grave problems of democratic legitimacy that those

laws were intended to resolve." |

Buckley v Valeo (1976) Citizens United v F.E.C (2010) Essay Citizens

United: The Story Behind the Case Questions 1. Do you

agree that campaign financing laws raise

serious First Amendment issues?

2. How strong is the government interest in preventing very wealthy individuals or corporations from having undue influence over election outcomes? 3. How strong is the government interest in preventing individuals or corporations from effectively "buying access" to candidates that they support financially? 4. Should corporations enjoy First Amendment rights? Is there any basis for distinguishing between free speech rights of a media corporation, such as the New York Times, and the free speech rights of a companies such as Coca Cola or Haliburton?

|