|

There is, not surprisingly, debate on the Court as to what sort of places and fora should be considered non-public. Greer v Spock considers restrictions on handbill distribution and speechmaking at Fort Dix Army Base in New Jersey. Dr. Benjamin Spock and others challenged restrictions on speech, arguing that since the base welcomed civilian speakers and had entertained musical concerts and other expressive activities in the past, it should be considered a public forum. The Court, however, disagreed. Fort Dix was a non-public forum, so restrictions on speech need only be reasonable and viewpoint neutral in order to pass First Amendment muster. In Greer, the Court (over dissents) concluded that the challenged restrictions on speech served the army's goal of keeping its troops focused on military preparedness. Cornelius v NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund also found the Court divided over whether the forum in question should be considered non-public. In Cornelius, the forum was not a place, but a federal fund drive. Each of over 200 charities accepted for inclusion in the federal employee fund drive was invited to prepare a 30-word description of their charitable activities to encourage payroll donations that would be directed their way. Several excluded charities sued, arguing that the critieria used to exclude them from the fund drive violated the First Amendment. They also attempted to argue that the fund drive was a designated public forum. The Court, however rejected their argument, finding the drive to be a non-public forum. So long as the criteria used for determining eligibility for participation in the fund drive were reasonable and viewpoint neutral, the Court said, the First Amendment was not offended. (The Court, finding some "evidence" of viewpoint discrimination, remanded the case to the trial court on that issue.) In Board

of

Airport Commissioners v Jews for Jesus, we

see that even in what is

arguably a non-public forum (the Court says it

need not decide whether

Los Angeles International Airport is a traditional

public forum or a non-public

forum), speech restrictions may run afoul of the

First Amendment.

The Court finds LAX's ban on "all First Amendment

activities" to be so

overbroad as to offend even the lax reasonableness

test applicable to the

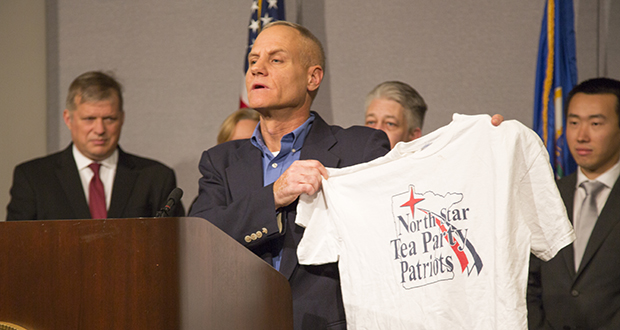

non-public forum.  A co-founder of the Minnesota Voters Alliance displays a T-shirt deemed unacceptable for wearing while voting. In the

2018 case of Minnesota Voters Alliance

v Mansky, the Court considered a Minnesota

ban on the wearing of certain types of campaign-related

apparel in the immediate vicinity of polling

places. The ban reached everything from

buttons and T-shirts promoting specific candidates

to clothing items that were closely identified

with campaign issues (e.g, an NRA T-shirt or one

that included the text of the 2nd Amendment, Tea

Party T-shirts, etc). In his opinion for the

Court, Justice Roberts noted that a polling

station is a government place established for a

specific purpose (voting) and thus is a non-public

forum. Therefore, the Minnesota law should

be upheld if it is reasonably designed to further

a significant state interest such as keeping peace

among voters, providing a dignified atmosphere for

voting, avoiding undue pressure on voters,

etc. While the Court found these interests

to be significant, it nonetheless struck down the

Minnesota law, finding its application to be too

arbitrary and giving too much discretion to

election officials to decide what clothing was too

political to be permitted. |

Greer v Spock (1976) Cornelius v NAACP Legal Defense Fund (1985) Bd. of Airport Commissioners v Jews for Jesus (1987) Minnesota Voters Alliance v Mansky (2018)

Dr. Benjamin Spock, famed baby doctor and anti-war activist. Spock argued (unsuccessfully) that his First Amendment rights were violated when he was denied the right to speak at the Fort Dix Army Base.

Entrance to Fort Dix, with sign on gate saying "Visitors Welcome."

Two respondents in Greer v Spock distributing pamplets, just prior to their arrest, inside entrance to Fort Dix. Questions 2. If a President is allowed to speak at a military base, must the President's election opponent be allowed to speak as well? Should your answer depend upon what the President said in his address? 3. If a base commander allows a civilian to address troops about the dangers of drug abuse, must he also allow a civilian to address troops about how the dangers of drug abuse are exaggerated? 4. Could a base commander ban all newspapers and magazines? 5. Does it appear to you that the federal government practiced viewpoint discrimination in its federal employee fund drive (Cornelius)? If so, what viewpoint was it discriminating against? 6. Why not simply let all charities participate, and leave employees free to support any charitable cause that they choose? 7. Is the test for designated public forums used in Cornelius "circular," as the dissenters contend? |