|

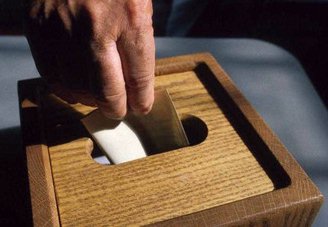

The right to vote is the fundamental right that has been the source of the most significant Supreme Court litigation. The Constitution addresses voting in Article II and four subsequent amendments (the 15th, forbidding discrimination in voting on the basis "of race, color, or previous condition of servitude;" the 19th, forbidding discrimination in voting based on sex; the 24th, prohibiting "any poll tax" on a person before they can vote; and the 26th, granting the right to vote to all citizens over the age of 18). The Court has chosen to also strictly scrutinize restrictions on voting other than those specifically prohibited by the Constitution because, in its words, the right to vote "is preservative of other basic civil and political rights." It should be noted, however, that "strict scutiny" in the fundamental rights cases tends to be, in actual practice a little less strict than in suspect classifications cases. The Court, for example, has upheld reasonable (e.g., 50-day) residency restrictions on voting and state laws denying the vote to convicted felons. Reynolds v Sims (1964) considered a challenge to the malapportionment of the Alabama legislature. The Court invalidated Alabama's apportionment scheme, which gave voters in rural areas disproportionately more power (more representatives per capita) than urban voters. Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Warren declared, "Legislators represent people, not trees or acres," and that the "Equal Protection Clause requires that seats in both houses of a bicameral legislature must be apportioned on a population basis." In Harper v Virginia Board of Elections (1966), the Court struck down a tax of $1.50 that Virginia required voters to pay to vote in state elections. (The 24th Amendment, adopted in 1964, already made it unconstitutional to enforce a poll tax in federal elections.) Writing for the Court, Justice Douglas said the right to vote was "a fundamental political right because it is preservative of all rights." The Court concluded that the tax was subject to strict scrutiny: "We have long been mindful that, when fundamental rights and liberties are asserted under the Equal Protection Clause, classifications which might invade or restrain them must be closely scrutinized and carefully confined." Kramer v Union Free School District (1969) is an example of a case in which strict scrutiny resulted in the invalidation of a state voting restriction. The Court found for a bachelor living with his parents, who challenged a N.Y. law that limited voting in school board elections to persons who either owned or leased property in the district or had children attending schools in the district. The Court found the law was not sufficiently narrowly tailored to serve its interest of limiting voting to interested persons. Easily the most controversial decision involving the Equal Protection Clause was Bush v Gore, the Supreme Court decision that ended the Florida recount and effectively decided the presidential election of 2000 in favor of George W. Bush. Although the vote to stop the recount was 5 to 4, seven justices found an equal protection problems with Florida's using different criteria to measure voter's intent in different counties (what to do about hanging chads and dimpled chads, for example--remember?) and with re-examining the ballots of "undervoters" (ballots not recorded because it was initially determined that the voter did not vote for any presidential candidate) but not those of "overvoters" (ballots not recorded for any presidential candidate because it was initially determined that the voter voted for two or more presidential candidates). Two of the justices (Breyer and Souter), however, would have sent the matter back to Florida with instructions to develop a statewide standard for determining the intent of voters--but five justices believed it was too late for that. Many critics of Bush v Gore suggest that varying standards for measuring the intent of voters can be found in virtually every state in the country, and the decision presents many opportunities for future challenges to results in close elections. The opinion, however, strongly suggests that the it is a ticket good for one ride only. In addition to the Equal Protection problem in Bush v Gore, three justices (Thomas, Scalia, and Rehnquist) would have stopped the recount based on what they saw was a violation of Article II, Section One of the Constitution which says that "Each State shall appoint, in such manner as the legislature thereof shall direct, a number of electors..." According to these three justices, the opinion of the Florida Supreme Court usurped a job delegated to the Florida legislature.  Mary-Jo Criswell, a Democratic voter in Indiana who challenged that state's strict voter id law. (photo by AJ Mast for the New York Times) In 2008, in Crawford v

Marion County Election Board, the Supreme Court considered a

challenge to

Indiana's strict voter identification law. In upholding a law

that required voters to present either a driver's license, a passport,

or a state-issued photo identification card, three justices (Scalia,

Thomas, and Alito) believed Indiana's law should be subjected only to

rational basis scrutinty, and that the state's interest in preventing

vote fraud constituted a rational basis. Three other justices

(Stevens, Roberts, and Kennedy) allowed that an as-applied challenge

might have merit for a voter that could show that the law places a

substantial burden on his or her ability to vote. In such cases,

heightened scrutiny might be justified, even though such scrutiny was

not appropriate for a facial challenge to the law. Three

dissenting justices (Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer) concluded, using a

balancing test, that Indiana's interest in preventing voter fraud did

not justify the significant burden that the law placed on specific

groups of voters (such as the homeless and elderly residents who did

not drive cars). Voter ID laws are typically backed by Republican

legislators (all Republican legislators in Indiana voted for the law)

and opposed by Democratic legislators (all Democratic legislators in

Indiana voted against the law). Practically everyone agrees that

the citizens who are most likely to be discouraged from voting by

strict voter ID laws tend, disproportionately, to vote Democratic.

|

Reynolds v Sims (1964) Kramer v Union Free School District (1969) Bush v Gore (2000) Crawford v Marion County Election Bd. (2008) Questions 2. If the federal government can have one legislative body (the Senate) apportioned on a basis other than population, why can't states do the same? For example, why couldn't a state senate have one senator from each county? 3. Do you think a law prohibiting ex-felons from voting should have survived strict scrutiny? Should one mistake at age 19 (for example a conviction for selling drugs) result in that person never again being able to participate in the state's electoral process? (Note that some states, such as Vermont, permit incarcerated felons to cast ballots in prison.) 4. The population in different legislative districts cannot be made precisely equal, and populations keep changing. How close in population should districts have to be to satisfy the demands of the Equal Protection Clause? 5. How serious in the injury suffered by some Florida voters that was the basis for the Court's conclusion that the recount scheme violated the Equal Protection Clause? Does it compare to the injury suffered in the "one person, one vote" cases involving apportionment? 6. Malapportionment distorts the political processes in a way making a legislative remedy of the problem unlikely, thus providing an argument for strict judicial scrutiny. Can the same be said about the problem identified in Bush--that it is the sort of invidious discrimination that will never be corrected without judicial intervention? 7. How do you explain the fact that the five most conservative members of the Court--the five most likely to take states' rights stances in most cases-- were the five most willing to find a violation of federal law in Bush v Gore? 8. Do you agree with the assertion that Bush v Gore was "pure politics" and not a reflection of judicial principles? Why or why not? 9. Judge Richard Posner, in his Breaking the Deadlock: The 2000 Election, the Constitution, and the Courts, offers an interesting argument in support of the Court's decision in Bush v Gore. Posner supports the decision because it avoided the chaos of a prolonged unresolved deadlock. Do you agree that that reason is enough to justify the decision? 10. The evidence is compelling that voter impersonation, the only type of voter fraud addressed by voter ID laws, is an exceedingly rare crime. The risks of being caught, the heavy punishment that can be levied, and the very tiny probability that an additional vote for a candidate will affect an election outcome account for the crime's extreme rarity. Given the fact that the problem addressed is non-existent, and the equally clear evidence that the voters discouraged by voter ID laws are likely to vote disproportionately Democratic, is it at all surprising that the 6 justices voting to uphold Indiana's voter ID law were all appointed by Republican presidents and that the 3 dissenting justices were all appointed by Democratic presidents?

|