|

Supreme Court interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause has come full circle. From its narrow reading of the clause in 1878 in Reynolds, to its much broader reading of the clause in the Warren and Burger Court years, the Court returned to its narrow interpretation in the controversial 1990 case of Employment Division of Oregon v Smith. The Court's decision in Smith provoked almost unanimous criticism on Capitol Hill, and Congress quickly responded by passing the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, designed to restore the test abandoned in Smith. This effort, however, largely was to fail, as the Supreme Court ruled that Congress lacked the power to compel state accomodation of significantly burdened religious beliefs and practices. In the mid-80s, the Supreme Court, while still using heightened scutiny, began to take a more skeptical view of Free Exercise claims. In 1986, the tide turned against Free Exercise claimants when the Court rejected, 5 to 4, the seemingly sympathetic request of an Orthodox Jewish army psychiatrist who felt religiously-compelled to wear a yamulke on duty, and who asked to be exempted from the military's ban on such headwear (Goldman). Lyng v Northwest Protective

Cemetery Association in 1988 provided

a major hint of the revolution in Free Exercise

law to come by adopting a per se rule that

the government need not concern itself with the

impact that its land use decisions might have on

religious practices. Based on this newly

announced principle, the Court permitted the

United States to proceed with construction of a

road through a national forest that would

concededly have severe consequences for the

practitioners of a Native American religion who

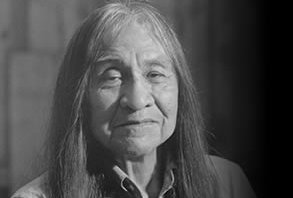

considered the area sacred.  Alfred Smith was denied unemployment benefits because of his peyote use The big

development--shocking to some--in Free Exercise

jurisprudence came in Employment Division v

Smith in 1990. Reinterpreting and, in

some cases, throwing out decades of caselaw, five

members of the Supreme Court concluded that a

generally applicable criminal law raises no Free

Exercise issues at all, ending what had long been

the obligation of states to demonstrate at least

an important state interest and narrow tailoring

when they enforced laws that significantly

burdened religious practice. The Court

reinterpreted some Free Exercise cases such as Yoder

as "hybrid" cases, raising both Free Exercise and

substantive due process issues. Other cases

such as Sherbert, Thomas, and Hobbie

were placed in the special category of

"unemployment compensation rules" --and left

undisturbed. From now on, the five-member

majority proclaimed, states will have to satisfy

heightened scrutiny (except for hybrid cases and

unemployment cases) only when a law specifically

targets religious practice. The Smith decision proved as

unpopular with Congress as it did with many

within the religious community. Congress

in 1993 responded to the Smith

decision by voting overwhelmingly to pass the

Religious Freedom Restoratation Act of 1993

designed to return religious exercise cases to

the pre-Smith standard for laws burdening

religious practices. Under RFRA,

federal, state, and local laws interfering

with religious exercise would have to be

supported by a compelling state interest and

be a least restrictive of religious freedom as

possible. The Supreme Court, however,

gets the last word on issues of constitutional

interpretation. In 1997, in City of Boerne

v Flores, the Court ruled that RFRA was

unconstitutional, at least as applied to state

and local governments. The Court

concluded that the Constitution, and in

particular Section 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment, gave no power to Congress to do

more than adopt remedial measures consistent

with Fourteenth Amendment interpretations of

the Court, and that Congress had instead tried

to changed the substantive law--substituting

its interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause

for that of the Supreme Court.

Religious Freedom Restoration

Act (RFRA)(1993)

Full text of the federal law that attempted to restore the pre-Smith test for laws significantly burdening religious exercise. The Act relied on Congress's power under Section 5 of the 14th Amendment to "enforce the provisions" of the Amendment, specifically its powers to enforce the Free Exercise Clause. The Supreme Court found in Bourne that Congress lacked the power to enforce the 14th Amendment in a way inconsistent with the Court's interpretations of the Amendment. Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA)(2000) Full text of the federal law enacted to overcome Supreme Court objections to RFRA. The Act, somewhat narrower in scope than RFRA, relies on Congress's powers under the Commerce Clause and the Spending Clause. |

Congress

shall

make no law respecting an

establishment of religion, or

prohibiting the free exercise thereof. (Amendment

1) TEST FOR

FREE EXERCISE CLAUSE VIOLATIONS Cases See Also:

Questions 2. Is the Court's conclusion in Smith that the law imposes no limitations on government's ability to enforce criminal laws of general applicability consistent with the framers' original understanding? Why did the Court in Smith pay so little attention to the historical record on this matter? 3. After Smith, it would be possible for a state to prosecute a priest or minister who offers communion wine for distributing alcohol to a minor. Is such a prosecution likely to occur? Why not? Does this suggest that the real losers in Smith are religions that have relatively few adherents, and especially those that are unpopular? 4. What in the Constitution supports applying a different and more deferential standard when it is a military regulation, rather than a civilian regulation, that is alleged to impinge upon constitutional liberties (as the Court suggested in Goldman)? Would it be better to apply the same standard, recognizing (of course) that national security is an interest of the highest order? 5. What do you think about the argument of Justice Stevens in the Boerne case: that to grant the Catholic Church an exemption from zoning laws that would not be given to a non-religious institution violates the Establishment Clause? How would you resolve the tension between the Free Exercise Clause and Establishment Clause? 6. Justice Scalia argues in Smith that an honest application of the compelling state interest test in free exercise cases involving neutral laws would lead to anarchy and chaos, with religions of all sorts getting exemptions from a wide variety of laws and programs. Is he right? Has the Court been using a "watered down" compelling state interest test in free exercise cases? 7. If the compelling state interest teest were to be applied in Smith, would Oregon have been able to satisfy it? How strong is the state's interest in prohibiting the use of peyote in the religious ceremonies of Native Americans? 8. The Religious Freedom and Restoration Act of 1993 passed in the Senate on a vote of 96 to 3. Does that vote suggest that support for the weakened free exercise test of Smith is diffuse at best? Links

|