|

The

Court has developed a number of theories upon

which state action sufficient to trigger the

protections of the Constitution might be

found. The "public function theory," applied

by the Court in the case of the park for whites

only involved in Evans v Newton, holds

that when certain traditional functions of

government are turned over to private parties, the

Constitution (in the case of Evans, the Equal

Protection Clause) will apply. The "judicial

enforcement theory" holds that judicial

enforcement of private discrimination may

constitute state action. Such state action

was found to exist in the case of Shelley v

Kraemer, where the state courts of Missouri

had been used to evict a black family from a home

they had bought from a white in violation of the a

restrictive covenant entered into by white

homeowners. Since almost all private

discrimination is supported at some level through

the courts (through application of race-neutral

trespass and contract law, for example), Shelley

leaves us to guess just what the exact limits of

its governing principle might be. A third

basis for finding state action is that the action

of the government is so entwined with the action

of the private parties that the complained about

action can be fairly attributed to the

government. This was found to be the case in

Burton v Wilmington, where the Eagle Coffee

Shoppe--which served only white customers--had

leased its space in a building owned by the City

of Wilmington. The Court found that the

presence of a "symbiotic relationship" between the

city and the private discriminators supported its

conclusion. On the other hand, a liquor

license issued by the city of Harrisburg,

Pennsylvania to a Moose Lodge that served only

whites was found insufficient to bring the Equal

Protection Clause into play (Moose Lodge v

Irvis).

The Eagle Coffee Shoppe, which served only whites, was located in this Parking Center owned by the city of Wilmington. The most recent of our cases, Edmonson

v Leesville Concrete, represents a

surprisingly lenient application of the state

action requirement. In Edmonson,

the Court found that a private defense

attorney's use of peremptory challenges to

exclude black jurors in a civil case constituted

state action. The Court found that the use

of peremptory challenges was authorized by

federal law and that there was judicial

assistance of the discrimination in the excusing

of the challenged juror. The Court also

described the selection of jurors as a

traditional state

function.

|

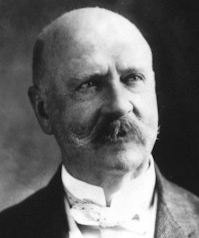

Shelley v. Kraemer (1948)

Senator Augustus Octavius Bacon, 1839-1914: creator of Baconsfield Park for the white people of Macon (Evans v Newton.) WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BACONSFIELD PARK?  Questions 2. Should the willingness of the Court to find state action depend upon the constitutional right that is alleged to have been violated? Should the Court, for example, be more willing to find state action when the claim is one of racial discrimination than when it is one of a denial of procedural due process? Should a private company granted a utility monopoly be able to cut off electricity to deadbeat customers without affording them an opportunity to be heard, but unable to offer electrical service to only, say, white customers? 3. What do you think Shelley means? Does the Court reach the result it did only because the Missouri courts had stepped in to frustrate a contract between a willing buyer and a willing seller? 4. Does Shelley mean that racially restrictive covenants are completely ineffective? 5. What if Harrisburg had only one liquor license to give, and it gave it to the Moose Lodge? Would that constitute state action? 6. What are the policy arguments for applying constitutional limitations only to governmental racial discrimination, not private racial discrimination? If racial discrimination is bad, why not interpret the Constitution to ban all forms of it? Do you agree that the Imperial Wizard of the KKK should be able to apply racially discriminatory criteria in choosing a marriage partner? In what guests he lets into his house? In what persons he lets into his store? 7. Does the surprisingly lenient application of the state action requirement in Edmonson come from the Court's strong distaste for racial discrimination in any form? 8. Do you agree or disagree with the suggestion of Justice O'Connor in her Edmonson dissent that the use of peremptory challenges should be viewed as "an enclave of private action in a government-managed proceeding"? |