|

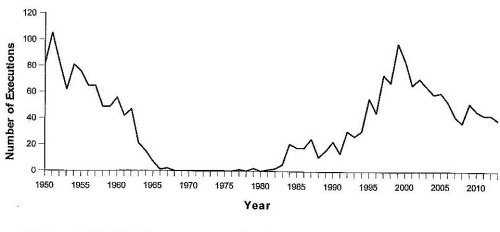

In 1958, in Trop v Dulles, the Court ruled 5 to 4 that cancelling U. S. citizenship as punishment for a crime was cruel and unusual punishment. In so doing, the Court announced a standard that would guide analysis in future death penalty cases. The Court in Trop said that the Eighth Amendment demanded that punishments "be consistent with evolving standards of decency." In the 1960s, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, led by Professor Anthony Amsterdam mounted a full-scale attack on the death penalty. Adopting a "moratorium strategy," the LDF succeeded in blocking all executions for five years, creating a "death-row logjam." In Furman v Georgia in 1972, the Court voted 5 to 4 to invalidate all then-existing death penalty laws based on the inherent arbitrariness of their application. In a key concurring opinion, justices said the randomness of being executed in the United States compared to "being struck by lightening." Most observers at the time concluded that there would never again be an execution in the United States. They were wrong. In 1976, in Gregg v. Georgia, the Court upheld Georgia's new capital-sentencing procedures, concluding that they had sufficiently reduced the problem of arbitrary and capricious imposition of death associated with earlier statutes. The law upheld in Gregg, which provided for bifurcated proceedings, one to determine guilt and one to determine whether to execute, has since become the model for statutes in death penalty states. In the death penalty phase of trials, jurors are now required to make specific findings concerning the presence or absence of mitigating and aggravating factors concerning the defendant's crime. The

Court

continued to

face questions concerning the appliction of the

death penalty: to

non-murderers,

to minors, to mentally disabled prisoners, to

racial minorities.

One such case is McCleskey v. Kemp (1987),

a challenge based on

a study that showed murderers of white victims

were far more likely to

be sentenced to death than murderers of black

victims. The Court continues to address the constitutionality of the death penalty in special contexts. In 2002, the Supreme Court held in Atkins v Virginia that the death penalty was unconstitutional when applied to the mentally retarded. Voting 6 to 3, the Court concluded that executions of the mentally retarded offended the "evolving standards of decency" test laid out in previous cases for evaluating the constitutionality of criminal punishments. The same test was applied in 2005 in Roper v Simmons to find that the death penalty could not be applied to persons under the age of 18 at the time of their crime. Justice Kennedy, for the 5 to 4 Court, wrote that "it is fair to say that the United States now stands alone in a world that has turned its face against the juvenile death penalty." Roper reversed a decision of the Court sixteen years earlier upholding such sentences. Cases Links

The Leopold & Loeb Case (1924) |

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Questions 2. On the other hand, doesn't the debate suggest that the framers--who could have chosen language explicitly authorizing the death penalty or all then-existing punishments, but instead chose vague language capable of multiple interpretations-- intended that the meaning of the Eighth Amendment change over time? 3. Even if the death penalty is constiutional, does it follow that all existing forms of the death penalty are constitutional. Is Florida's use of electrocution, for example, consistent with the cruel and unusual punishment clause? 4. Does the evidence suggest that the death penalty deters murder any more than a sentence of life without the possibility of parole? If it doesn't, does that suggest the death penalty is an excessive punishment? 5. What is the best argument for the death penalty? Is the death penalty necessary to deter life prisoners from committing murder in prisons? 6. How relevant to the Court's decision in Furman was the fact that at the time of the decision over 600 persons were on death rows around the country? 7. How much discretion should be given states to determine whether an individual is "mentally retarded," and therefore protected against infliction of the death penalty under Atkins v Virginia? |