|

If there is anything that the framers clearly intended to prohibit by way of the First Amendment it was prior restraints in the form of licensing laws that existed in England. Licensing laws have rarely been an issue in the United States, but another form of prior restraint (that is, legal restraint before publication) has received judicial attention: injunctions. The Supreme Court has said injunctions preventing the exercise of speech should be viewed very skeptically--they carry "a presumption of unconstitutionality." In Near v Minnesota in 1931, the Supreme Court considered an injunction issued by Minnesota courts against a scandal sheet called The Saturday Press. Determining several published pieces in the Saturday Press to have been "malicious, scandalous, or defamatory," the state courts enjoined publication of future issues. The Court, in a 5 to 4 opinion by Chief Justice Hughes, reversed, finding "the chief purpose" of the First Amendment being to prevent prior restraints. The Court said that after-publication punishment was much to be preferred: the state is less likely to suppress protected speech, the defendant can enjoy the safeguards of the criminal process, and courts will be in a better position to judge the allegedly unlawful speech. The Court did not rule out, however, upholding a prior restraint in some future case, suggesting that "the publication of sailing dates" or "location of troops in wartime" might be appropriate cases for an injunction. In 1971, the Nixon Administration went to court to stop publication of "the Pentagon Papers," a series of accounts based on a stolen, classified document entitled, "The History of U. S. Decision-Making on Viet Nam Policy." The Administration argued (among other things) that publication would threaten national security because other nations would be reluctant to deal with the U. S. if their dealings couldn't be kept secret. Acting with unusual haste (the three dissenting justices called the Court's action "irresponsibly feverish"), the Court in New York Times v United States concluded that a prior restraint on publication of excerpts from the Pentagon Papers violated the First Amendment. Two concurring justices indicated that they might have upheld the injunction if it were supported (as it was not) by a narrowly drawn congressional authorization.  U.

S. v Progressive presented an issue that

could have been a law school hypothetical designed

to test the limits of the presumption of

unconstitutionality attached to prior

restraints. The United States went to court

to enjoin publication of an article scheduled to

appear in the left-wing magazine, The

Progressive. The article, "The H-Bomb

Secret: How We Got It and Why We're Telling It,"

was essentially a how-to-do-it account for anyone

wanting to build an atomic bomb. Reasoning

that the article presented a clear and present

danger of speeding the efforts of foreign nations

or terrorist groups interested in developing

atomic weapons, a Wisconsin federal district judge

issued an injunction against publication.

(Later, the story was published outside the United

States, making the case moot. To date, no

direct harm has been traced to the story, said to

aid would-be bomb developers primarily by helping

them to avoid "blind alleys.")

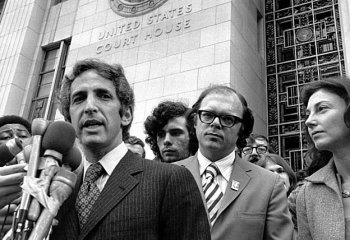

THE

ELLSBERG ("PENTAGON PAPERS") TRIAL

|

Near v. Minnesota (1931) New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) United States v. Progressive, Inc. (1979)

CBS "60 MINUTES" STORY ON THE

PENTAGON PAPERS CONTROVERSY AND THE POSE

Questions 2. What burden should the government have to meet to sustain a prior restraint? 3. Should prior restraints be sustained against speech that threatens specific individuals such as a story headlined, "Witnesses in the Federal Witness Protection Program--Where Are They Now?"? 4. One seemingly innocuous statement in published reports about the Pentagon Papers was attributed to Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. The Soviets knew that the quoted statement was made inside a Soviet limousine--a limousine that the CIA had succeeded in bugging. As a result, the bug was removed by the Soviets. Does this incident suggest that courts should defer to Administration judgments that there is a national security need to enjoin publication? 5. Should it make a constitutional difference whether the government seeks an injunction based on a federal statute authorizing such injunctions or whether it relies on inherent powers of the executive branch? 6. Do you find it surprising that much of the established media supported The Progressive in its litigation to lift the injunction against its publishing the how-to-build-it guide to atomic bombs? 7. What, if any, public policy goals are served by publication of information concerning the building of atomic weapons?

|