|

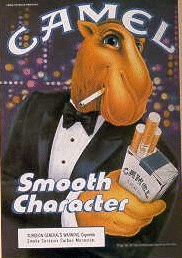

The Supreme Court for many years took the view that commercial speech--speech that proposes an economic transaction--was not protected by the First Amendment. The Court reasoned that the broad powers of government to regulate commerce must reasonably include the power to regulate speech concerning articles of commerce. This view changed in the 1970s in a series of cases invalidating state regulations affecting services such as abortion providers and products such drugs. In Virginia State Board of Pharmacy (1976), for example, the Court struck down a law prohibiting the advertising of prices for prescription drugs. The Court noted that price information was very important to consumers, and suggested that the First Amendment protects the "right to receive information" as well as the right to speak. Given the free speech interests at stake, the Court said, the state regulation must support a substantial interest. City of Cincinnati v Discovery Network is a somewhat atypical commercial speech case. The case involved a challenge to a local ordinance that--for aesthetic reasons-- banned newsracks for primarily commercial publications such as shoppers and real estate guides. The Court, 6 to 3, invalidated the law, noting that newsracks containing commercial publications are no uglier than newsracks containing traditional newspapers. The Court viewed the ordinance as content-based, and applied something close to strict scrutiny. Four years later in Central Hudson Gas & Electric v Public Service Commission the Court announced a test for evaluating commercial speech regulations that would be used in many subsequent cases. The Central Hudson test recognizes the constitutionality of regulations restricting advertising that concerns an illegal product or service, or which is deceptive. For all other restrictions on commercial speech, however, the Court's test requires that the government show that the regulation directly advances an important interest and is no more restrictive of speech than necessary. 44 Liquormart v Rhode Island (1996), a decision invalidating a state law prohibiting price advertising of alcohol, is significant in several respects. First, the Court emphatically rejects the suggestion made in a case a decade earlier that states have greater freedom to restrict advertising related to "vices" than other types of economic activities. The Court also makes clear that the power to ban a product completely (in this case under the 21st Amendment) does not carry with it the "lesser power" to restrict advertising concerning that product. Finally, several justices in 44 Liquormart question whether the test for restrictions on non-misleading commercial speech should be the form of intermediate scrutiny suggested in Central Hudson-- indicating that they might favor something closer to the strict scrutiny applied to other content regulations of speech. The

Court avoided revisiting the question of the

proper test for commercial speech regulations in

its 2001 decisions in United States v United

Foods and Lorillard Tobacco Co. v

Reilly. The Court in United Foods

struck down a law that required mushroom growers

to financially support generic mushroom

advertising. The Court concluded that the

regulation was an unconstitutional form of

compelled speech--enough if commercial speech is

entitled to less than full First Amendment

protection. In Lorillard, the Court

invalidated a series of Massachusetts regulations

restricting the advertising of tobacco

products. Writing for the Court, Justice O'

Connor noted that several members of the Court had

previously argued for applying strict scrutiny to

laws restricting commercial speech, but said that

since the state could not meet even the

intermediate standard of scrutiny, there was "no

need to break new ground."

|

Virginia State Bd. of Pharmacy v Virginia Citizen's Consumer Council (1976) 44 Liquormart v Rhode Island (1996) City of Cincinnati v Discovery Network (1993) Lorillard Tobacco Co. v Reilly (2001) United States v United Foods (2001)

Questions 2. Why would Virginia pass a law prohibiting the price advertising of drugs? Who benefits from such a law? Who is hurt by such a law? 3. Does it make sense to say, as the Court does, that the First Amendment protects "the right to receive information"? What information do we have a right to receive? 4. Should a state be able to prohibit advertising for a service or product that is illlegal in that state, but not in others? For example, can any of the 49 states that criminalize prostitution ban an advertisement for a brothel in Nevada, where such establishments are legal under a county option? 5. What test do you think should be used to analyze commercial speech restrictions? 6. What do you make of the Court's continued reliance (in the 2001 decisions) of the Central Hudson test to strike down commercial speech regulations, while at the same time indicating its refusal to endorse such a test? 7. Can a state ban billboards advertising sexually-oriented businesses? (See 8th Circuit's decision in case involving such a ban by the state of Missouri.) |