John Lilburne, quoting the Bible

Political

firebrand who began his career as a martyr for Puritan doctrine, became

a

champion of the Levellers and political democracy, and ended his days

as a

Quaker and pacifist.

http://www.british-civil-wars.co.uk/biog/lilburne.htm

“...If

the World was emptied of

all but John Lilburne, Lilburne would quarrel with John, and John with

Lilburne...” http://www.british-civil-wars.co.uk/biog/lilburne.htm

John Lilburne, c.1615-1657: John Lilburne was born in Sunderland,

the third son of a minor country gentleman. After attending schools in

Bishop

Auckland and Newcastle-upon-Tyne, he

was

apprenticed to Thomas Hewson, a London

clothier and Puritan. He remained with Hewson from around 1630 to 1636.

During

his apprenticeship, Lilburne immersed himself in the Bible, Foxe's Book

of

Martyrs and the writings of the Puritan divines. In 1636, he was

introduced

to the Puritan physician John Bastwick, an active pamphleteer against

episcopacy

who, with William Prynne and Henry Burton, was persecuted by Archbishop

Laud in

a famous case in 1637. From:

British

Civil Wars, Commonwealth and Protectorate 1638-60

http://www.british-civil-wars.co.uk/biog/lilburne.htm

John

Lilburne: The First English Libertarian: He

became known to his contemporaries

as "Freeborn John." He described himself as "a lover of his

country and sufferer for the common liberty." His biographer Pauline

Gregg

concluded: He could be called the first English Radical — a

great-hearted

Liberal — a militant Christian — even if the spirit of his teaching

were taken

fully into account, the first English democrat. But it is better to

leave him

without a label, enshrined in the words he spoke for his party: "And

posterity we doubt not shall reap the benefit of our endeavours, what

ever

shall become of us." His courageous

campaigns for liberty resulted in him spending much of his life in

prisons.

These included Fleet prison in London, Oxford Castle,

the notorious Newgate prison also in London,

the Tower of London, Mount

Orgueil Castle in Jersey, and Dover Castle. When

Lilburne was brought before the court of

Star Chamber, he refused to take the oath. "It is this trial that has

been

cited by constitutional jurists and scholars in the United States of America

as being

the historical foundation of the Fifth Amendment to the United States

Constitution. It is also cited within the 1966 majority opinion of Miranda

v Arizona

by the U.S. Supreme Court." The

late United States Supreme Court Judge Hugo Black, who often cited the

works of

John Lilburne in his opinions, wrote in an article for Encyclopaedia

Britannica that he believed John Lilburne's constitutional work of

1649

was the basis for the basic rights contained in the U.S. Constitution. By: Peter Richards at http://mises.org/story/2861

The

Levellers: The Levellers

were a group of political activists in the 17th century, who campaigned

for

radical change, by writing and distributing pamphlets, petitions and

manifestos; and by arranging meetings in taverns to spread their ideas.

Among

their leading writers and pamphleteers, besides John Lilburne, were

Richard

Overton, William Walwyn, Thomas Prince, and John Wildman.

Probably the most famous document compiled by

the Levellers is one entitled An

Agreement of the People. http://www.constitution.org/lev/eng_lev_07.htm The demands listed included regular

elections, religious freedom, equality before the law, an end to

conscription

for war service, equal electoral districts according to population, and

universal manhood suffrage. By: Peter Richards at http://mises.org/story/2861

Selected

Works of the Levellers: The

Levellers were a group of English

reformers mainly active during the period from 1645 through 1649, who

originated many of the ideas that eventually became provisions of the

U.S.

Constitution, especially the Bill of Rights. Inspired by the Petition

of

Right of 1628, and led by John Lilburne, beginning as a lieutenant

of

Oliver Cromwell, they initially supported the Protectorate, but then

turned

against it when Cromwell failed to make the reforms they demanded. The

response

was the prosecution of most of its leaders, who were either imprisoned

or

executed. Their proposals continued, however, to inspire political

philosophers

and future generations of reformers. They appear to have influenced

their

contemporary, Thomas Hobbes, and later writers such as James Harrington

and

John Locke. Their proposals were revived during the Revolution of 1688

to

produce the English Bill of Rights in 1689, which led to the Whig party

in Britain that

supported many of the reforms for Britain sought

by the Americans during the War of Independence. During the period of

their

greatest activity, the Levellers produced a number of political

documents,

which have been gathered and published by various editors. We present

several

of those collections here, which have some overlap in their contents. http://www.constitution.org/lev/levellers.htm

“Agreement

of the Free people of England”: This

manifesto for constitutional reform in Britain paved the way for

many of

the civil liberties we cherish today: universal vote, the right to

silence in

the dock, equal parliamentary constituencies, everyone being equal

under the

law, the right not to be conscripted into the army, and many others.

This

particular version was smuggled out of the Tower of London,

where Lilburne and the others were being held captive. All Leveller

soldiers,

and they were the majority in many regiments, carried this agreement

proudly

tucked into their hat-band. http://www.constitution.org/eng/agreepeo.htm

British

History Online: This searchable

database provides full text access to the proceedings and

documents of the House of Lords and Commons during the time of John

Lilburne’s

trials. Search : John

Lilburne

Journal of the House of Lords: Volumes

4 – 10, 1629-1649

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/subject.aspx?subject=6&gid=44

Journal of the House of Commons: Volumes

1 – 12, 1547-1699

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/subject.aspx?subject=6&gid=43

Star-Chamber

February, 1637: “Information

was preferred in Star-Chamber by the King's Attorney-General, against

John

Lilburne and John Warton, for the unlawful Printing and Publishing of

Libellous

and Seditious Books, Entituled News from Ipswich, &c. they were

brought up

to the Office, and there refused to take an Oath to answer

Interrogatories, saying

it was the Oath ex Officio, and that no free-born English man ought to

take it,

not being bound by the Law to accuse himself, (whence ever after he was

called

Free-born John ) his offence was aggravated, in that he printed these

Libellous

and Seditious Books, contrary to a Decree in Star-Chamber, prohibiting

printing

without License: which Decree was made this Year in the Month of July,

and was

to this effect.”

From: 'Historical

Collections: 1637 (3 of

5)', Historical Collections of Private Passages of State: Volume 2:

1629-38

(1721), pp. 461-481.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=74904&strquery=john

lilburne

Star Chamber

‘Condigne Punishment’ of John Lilburne – 1637:

“Ordered

ye 18th Touching Lilburne Prison[e]r in the Fleete: Where as John

Lilburne

Prison[e]r in the Fleet by Sentence in Starr Chamber did this day

suffer

condigne Punishment for his sev[er]all offences, by whipping at a cart

and

standing in the pillory and as their Lo[rdshi]pps were this day

informed,

during the time that his Body was under the said execution, audatiously

and

wickedly not only utter sundry scandalous and seditious speeches, but

likewise

scattered sundry Copies of seditious Bookes amongst the people that

beheld the

said execut[i]on for w[hi]ch very thing amongst other offences of like

nature

hee had beene censured in the said co[u]rt by the foresaid Sentence It

was

thereupon ordered by their Lo[rdshi]pps That the said Lilburne should

bee Layed

alone w[i]th Irons on his hands and Leggs in the wardes of the Fleete,

where

the basest and meanest sorte of Prison[e]rs are used to bee putt, And

that the

Warden of the Fleete take especiall care to hinder resort of any

p[er]son

whatsoever unto him, and p[ar]ticularly that hee bee not supplyed

w[i]th any

hand, And that hee take especiall notice of all L[ette]res Writings and

Books

brought unto him, and seaze and deliver the same unto their

Lo[rdshi]pps, And

take notice from time to time, who they bee that resort to the said

Prison to

vissitt the said Lilburne or to speake w[i]th him, and informe the

Board. And

it was lastly ordered, that hereafter all p[er]sons that shalbee

p[ro]duced to

receave Corporall punishm[en]t according to Sentence of that Court or

by order

of the Board, shall have their Garment[e]s searched before they bee

brought

forth, and neither writing nor other Thing suffered to bee about them,

and

their hands likewise to bee bound during the time they are under

punishm[en]t,

whereof (together w[i]th the other p[re]mises) the said Warden of the

Fleete,

is hereby required to take notice and to have especiall care, that this

their

Lo[rdshi]pps order bee accordingly observed.” http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/citizenship/rise_parliament/transcripts/star_chamber.htm

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/citizenship/rise_parliament/docs/star_chamber.htm

Lilburn's

Judgement by the House of Lords 1646:. "It is to be

remembered, that, the Tenth

Day of July, in the Two and Twentieth Year of the Reign of our

Sovereign Lord

King Charles, Sir Nathaniell Finch Knight, His Majesty's Serjeant at

Law, did

deliver in, before the Lords assembled in Parliament at Westm'r,

certain

Articles against Lieutenant Colonel John Lilburne, for High Crimes and

Misdemeanors done and committed by him, together with certain Books and

Papers

thereunto annexed; which Articles, and the said Books and Papers

thereunto

annexed, are filed among the Records of Parliament; the Tenor of which

Articles

followeth, in these Words:

"It

was then and there, (that is to say,) the said Tenth Day of July, by

their

Lordships Ordered, That the said John Lilbourne be brought to the Bar

of this

House the 11th Day of the said July, to answer the said Articles, that

thereupon

their Lordships might proceed therein according as to Justice should

appertain;

at which Day, scilicet, the 11th Day of July, Anno Domini 1646, the

said John

Lilburne, according to the said Order, was brought before the Peers

then

assembled and sitting in Parliament, to answer the said Articles; and

the said

John Lilburne being thereupon required, by the said Peers in

Parliament, to

kneel at the Bar of the said House, as is used in such Cases, and to

hear his

said Charge read, to the End that he might be enabled to make Defence

thereunto, the said John Lilburne, in Contempt and Scorn of the said

High

Court, did not only refuse to kneel at the said Bar, but did also, in a

contemptuous Manner, then and there, at the open Bar of the said House,

openly and

contemptuously refuse to hear the said Articles read, and used divers

contemptuous Words, in high Derogation of the Justice, Dignity, and

Power of

the said Court; and the said Charge being nevertheless then and there

read, the

said John Lilburne was then and there, by the said Lords assembled in

Parliament, demanded what Answer or Defence he would make thereunto;

the said

John Lilburne, persisting in his obstinate and contemptuous Behaviour,

did

peremptorily and absolutely refuse to make any Defence or Answer to the

said

Articles; and did then and there, in high Contempt of the said Court,

and of

the Peers there assembled, at the open Bar of the said House of Peers,

affirm,

"That they were Usurpers and unrighteous Judges, and that he would not

answer the said Articles;" and used divers other insolent and

contemptuous

Speeches against their Lordships and that High Court: Whereupon the

Lords

assembled in Parliament, taking into their serious Consideration the

said

contemptuous Carriage and Words of the said John Lilburne, to the great

Affront

and Contempt of this High and Honourable Court, and the Justice,

Authority, and

Dignity thereof; it is therefore, this present 11th Day of July,

Ordered and

Adjudged, by the Lords assembled in Parliament, That the said John

Lilburne be

fined, and the said John Lilburne by the Lords assembled in Parliament,

for his

said Contempt, is fined, to the King's Majesty, in the Sum of Two

Thousand

Pounds: And it is further Ordered and Adjudged, by the said Lords

assembled in

Parliament, That the said John Lilburne, for his said Contempts, be and

stand

committed to The Tower of London, during the Pleasure of this House:

And

further the said Lords assembled in Parliament, taking into

Consideration the

said contemptuous Refusal of the said John Lilburne to make any Defence

or

Answer to the said Articles, did Declare, That the said John Lilburne

ought not

thereby to escape the Justice of this House; but the said Articles, and

the

Offences thereby charged to have been committed by the said John

Lilburne,

ought thereupon to be taken as confessed: Therefore the Lords assembled

in

Parliament, taking the Premises into Consideration, and for that it

appears by

the said Articles that the said John Lilburne hath not only maliciously

published several scandalous and libelous Passages of a very high

Nature

against the Peers of this Parliament therein particularly named, and

against

the Peerage of this Realm in general, but contrived, and contemptuously

published, and openly at the Bar of the House delivered, certain

scandalous

Papers, to the high Contempt and Scandal of the Dignity, Power, and

Authority

of this House: All which Offences, by the peremptory Refusal of the

said John

Lilburne to answer or make any Defence to the said Articles, stand

confessed by

the said Lilburne as they are in the said Articles charged:

"It

is, therefore, the said Day and Year last abovementioned, further

Ordered and

Adjudged, by the Lords assembled in Parliament, upon the whole Matter

in the

said Articles contained,

"1. That

the said John Lilburne be sined to the King's Majesty in the Sum of Two

Thousand Pounds.

"2.

And, That he stand and be imprisoned in The Tower of London, by the

Space of

Seven Years next ensuing.

"3.

And further, That he, the said John Lilburne, from henceforth stand and

be

uncapable to bear any Office or Place, in Military or in Civil

Government, in

Church or Commonwealth, during his Life."

From: 'House of Lords Journal

Volume 8: 17 September 1646',

Journal of the House of Lords: volume 8: 1645-1647 (1802), pp. 493-494.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=34103&strquery=john

lilburne

Lilburne on

Trial for High Treason: On

the October 24, Lieutenant Colonel John Lilburne was charged under the

Treason

Acts of May 14 and July 17, 1649 — acts passed no doubt with the

express

purpose of charging Lilburne with high treason. The trial began early

on the

morning of October 25, after the members of the Extraordinary

Commission of

Oyer and Terminer, consisting of 40 dignitaries led by the lord mayor,

took

their places in the Guildhall in London

to preside over the case. The courtroom was packed with Lilburne's

friends and

supporters. Lilburne contested point after point and when the

prosecution read

out extracts from Lilburne's pamphlets, the public often applauded.

After the

indictment was read out, Lilburne requested more time to prepare his

defense

and gather witnesses. He was granted an afternoon's respite only. The

court

reconvened at 7 AM the following morning. After a long day of listening

to

Lilburne being subjected to intense questioning, the jury finally

retired at 5

PM. Within an hour they reached their verdict: not guilty of all

charges.

Cheers rang out in the courtroom and celebrations continued all

evening. Church

bells tolled throughout London,

bonfires were lit and feasting was enjoyed by John's many supporters. A

special

medal was struck to commemorate the occasion, with John's portrait on

one side

and the names of the members of the jury on the other. John Lilburne

was

returned to the Tower, his release being delayed until November 8, when

his

fellow prisoners Walwyn, Overton, and Prince were also discharged. The

Levellers held a great feast at the King's Head Tavern in Fish Street

to celebrate the occasion. http://mises.org/story/2861#part27

5

Howell's State Trials 411-412, (1649) Statement of

John Lilburne: ‘For

certainly it cannot be denied, but if he be really an offender, he is

such by

the breach of some law, made and published before the fact, and ought

by due

process of law, and verdict of 12 men, to be thereof convict, and found

guilty

of such crime; unto which the law also hath prescribed such a

punishment

agreeable to that our fundamental liberty; which enjoineth that no

freeman of

England should be adjudged of life, limb, liberty, or estate, but by

Juries; a

freedom which parliaments in all ages contended to preserve from

violation; as

the birthright and chief inheritance of the people, as may appear most

remarkably in the Petition of Right, which you have stiled that most

excellent

law.‘And therefore we trust upon second thoughts, being the parliament

of

England, you will be so far from bereaving us, who have never forfeited

our

right, of this our native right, and way of Trials by Juries, (for what

is done

unto any one, may be done unto every one), that you will preserve them

entire

to us, and to posterity, from the encroachments of any that would

innovate upon

them * * *.‘And it is believed, that * * * had (the cause) at any time

either

at first or last been admitted to a trial at law, and had passed any

way by

verdict of twelve sworn men: all the trouble and inconveniences arising

thereupon and been prevented: the way of determination by major votes

of

committees, being neither so certain nor so satisfactory in any case as

by way

of Juries, the benefit of challenges and exceptions, and unanimous

consent,

being all essential privileges in the latter; whereas committees are

tied to no

such rules, but are at liberty to be present or absent at pleasure.

Besides,

Juries being birthright, and the other but new and temporary, men do

not, nor,

as we humbly conceive, ever will acquiesce in the one as in the other;

from

whence it is not altogether so much to be wondered at, if upon

dissatisfactions, there have been such frequent printing of men's

cases, and

dealings of Committees, as there have been; and such harsh and

inordinate heats

and expressions between parties interested, such sudden and importunate

appeals

to your authority, being indeed all alike out of the true English road,

and

leading into nothing but trouble and perlexity, breeding hatred and

enmities

between worthy families, affronts and disgust between persons of the

same

public affection and interest, and to the rejoicing of none but public

adversaries. All which, and many more inconveniences, can only be

avoided, by

referring all such cases to the usual Trials and final determinations

of law.’

John

Lilburne - Leveller

leader:

On

26 October 1649, amid tumultuous scenes at Westminster, a high-profile political

trial

ended in chaos. A jury had acquitted John Lilburne, the charismatic

leader of

the Levellers, of a charge of high treason against the recently formed English Republic. Within days a

commemorative

medal had been struck, bearing Lilburne's image and the names of the

jury. This

dramatic episode and the media frenzy with which it was surrounded

encapsulate

the romance of the Leveller movement and the potency of the threat

which

Lilburne was perceived to represent to the political establishment. Although he was acquitted in 1649, Lilburne

became a marked man. He was soon exiled to the Continent and then, upon

his illegal

return in 1653, was subjected to another set-piece trial and further

imprisonment. The Levellers, with Lilburne broken in body and spirit,

disintegrated as a political force, and Lilburne himself died a Quaker

in 1657.

However, Leveller ideas would resurface in different forms over the

ensuing

centuries; and 'Lilburnism', a dramatic new form of political activism,

never

disappeared. From the National Archives: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/citizenship/rise_parliament/leveller.htm

Judgment

against

Lilburne, 1652: According to

former Order, Lieutenant Colonel John Lilburne was this Day

brought to the Bar in the Parliamenthouse, to receive the Judgment

given

against him by the Parliament: And, being at the Bar, he was commanded

to

kneel; but he obstinately denied to kneel at the Bar; and thereupon was

commanded to withdraw.

From: 'House of Commons Journal Volume 7: 20

January 1652', Journal of the House of Commons: volume 7: 1651-1660

(1802), pp.

74-75.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=23935&strquery=john

lilburne

An Intercepted Letter 1653: “The

last weeke John Lilbourne was five times at his triall at the

sessions-house,

where he most couragiously defended himselfe from Mr. Steele the

recorder his

violent assaults, with his old buckler, magna charta; soe that they

have let

him alone, although he be not yeat quitted. Cromwell thought this

fellow soe

considerable, that during the time of his triall he kept three

regiments

continually in armes about St. James. There were many tickets throwne

about

with these words;

And what, shall then honest John Lilbourn

die?

Threescore thousand will know the reason why.

Lilbourne

encountred Prideaux with soe many opprobrious termes, that he caused

him

absolutely to quit the field. Titus was one of Lilbourne's accusers,

and the

duke of Buckingham's name is much used therein. Sir, I had almost

forgot to

acquaint you, that that arch-villaine Bampfield hath bin lately with

Cromwell;

but as for the particulars of his business I shall deferr untill

another my

next, not having time to enquire it out throughly, especially since I

keepe my

chamber, being in some seare of the vertigo. I believe you have senn

the new

declarion of the representative, otherwise you should have receaved it

from, For

Mr. Edwards theise are. Sir, your ever faithfull and obedient servant,

Peter

Richardson.”

From: 'State Papers, 1653: July (4 of 5)', A

collection of the State Papers of John Thurloe, volume 1: 1638-1653

(1742), pp.

363-376.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=55265

Resolved,

by the Parliament,

Nov. 1653, That the

Lieutenant of the Tower of London be enjoined and required to detain

and keep

the Body of Lieutenant John Lilburne in safe Custody, in the Tower of

London, and

not to remove or carry him from thence, notwithstanding any Habeas

Corpus

granted, or to be granted, for that Purpose, by the Court of

Upper-Bench, or

any other Court, until the Parliament take further Order.

From: 'House of Commons Journal Volume 7: 26

November 1653', Journal of the House of Commons: volume 7: 1651-1660

(1802),

pp. 358.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=24321&strquery=john

lilburne

From The Dutch ambassadors at London

to the States General 1653.

High and mighty Lords... we do presume that the government

here hath had

some notice of some secret correspondence and designs for king Charles;

for

which several persons of quality are put into the tower. Lieutenant

col.

Lilburne was likewise put there; but since he is sent to the islands of

Man, Guernsey, or Sorlings, there to

evaporate his turbulent

humours; whereof he is full, as they say here. 'Tis believed, that the

twelve

sworn jury-men, who did clear and discharge him, will not escape

unpunished

either in bodies or estates. The fleet of this state, which is said to

be an

hundred sail strong, or thereabouts, are most of them at sea although

others do

assure us of the contrary. We were glad to receive your lordships

resolutions

concerning the poor prisoners here, and we shall govern ourselves

therein for

the best advantage of the state. My lords, Westminster, 12/2 Sept. 1653. your lordships humble servant.

From: 'State Papers, 1653: September (1 of

6)', A collection of the State Papers of John Thurloe, volume 1:

1638-1653

(1742), pp. 445-455.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=55272&strquery=john

lilburne

The Just Defense

of John

Lilburne 1653 : Written while on trial for his life. An

activist

for nearly twenty years, and advocate for radical legal reforms, John

Lilburne

was accused of treason and tried in a hugely important trial. (When the

jury

refused to convict, he was re-arrested and imprisoned on the Isle of

Jersey,

out of reach of habeas corpus protections – shades of Guantanamo after

9/11.) http://www.strecorsoc.org/docs/defence1.html

Fear

of Public Reaction to Lilburne’s Trial 1653: “The business of lieutenant col.

Lilburne

hath been for these three days continually upon hearing, and after a

pleading

of twelve or sixteen hours long, was the day before yesterday ended in

the

night, and pronounced to his advantage and discharge, without being

released

out of prison: notwithstanding it is thought, that they will not leave

him so,

but bring him before a high court of Justice, and there accuse him of

treason

and other crimes; yea it is very certain, that many of the parliament

are very

bitter against him, and irritated the more by his book written in

prison,

wherein he doth grosly exclaim against them and their government.

Out

of fear of insurrections and

commotions, three regiments of foote and one of horse were sent for to

town,

who marcht through the city on Saturday last; and here were some

libells

scattered up and down not long since, that if Lilburne doe suffer

death, there

are twenty thousand, that will die with him. What further will be done

with

him, shall be advised to your excellency by the next.”

From:

'State Papers, 1653: August (5 of 5)', A collection of the State Papers

of John

Thurloe, volume 1: 1638-1653 (1742), pp. 435-445.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=55271&strquery=john

lilburne

Lilburne

Cleared by Jury 1653:

My

lord.....L. co1. John Lilburn is

cleared by a jury. There were six or seven hundred men at his trial

with

swords, pistolls, bills, daggers, and other instruments, that in case

they had

not cleared him, they would have imployed in his defence. The joy and

acclamation was so great after he was cleared, that the shout was heard

an

English mile, as is said; but he is not yet released out of prison, and

it is

thought they will try him at a high court of Justice.

Westminster, 26

Aug./5 Sept. 1653.

From:

'State Papers, 1653: August (5 of 5)', A collection of the State Papers

of John

Thurloe, volume 1: 1638-1653 (1742), pp. 435-445.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=55271&strquery=john

lilburne

Retrial

Likely 1653: My lord; .....

The proceedings against Lilburne Saturday last after a pleading of

sixteen

hours were determined, and he declared not guilty of any crime worthy

of death.

Since the twelve jurymen have been called to account before the

council, to

give an account of their verdict; and in the mean time he remaineth a

prisoner.

It seems, they will charge him with further crimes of treason, and will

judge

him by a high court of justice. There are two or three others of

quality put

into the tower about some plot for the service of the king; and that

they

should have held correspondence with the said Lilburn. I could with I

could

find more matter to entertain your lordship. My lord, Westminster, 26

Aug/5 Sept. 1653.

From:

'State Papers, 1653: August (5 of 5)', A collection of the State Papers

of John

Thurloe, volume 1: 1638-1653 (1742), pp. 435-445.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=55271&strquery=john

lilburne

“The Resurrection” of John

Lilburne 1655, Now a Prisoner in Dover-Castle: Two

letters by John Lilburne (one to his wife, Elizabeth, quoting a scrap

of hers)

and biblical analysis, written from prison and published on his

instruction to

explain to his friends and supporters that he had become a Quaker.

Lilburne

became a Friend during what was to be his final stay in prison,

declaring that

"by the spirit and power of life from God, that now aloud again speaks

within me ... I am at present become dead to my former busling actings

in the

world, and now stand ready... to hear and obey all things that the

lively voice

of God speaking in my soul require of me." http://www.strecorsoc.org/docs/resurrection1.html

Supreme

Court of the United States: References to John Lilburne:

Gannett Co. v. DePasquale: 443 U.S.

368 (1979). Sixth amendment right to a

public trial. “the first fundamental

liberty of an

Englishman” The Trial of John Lilburne” 4

How. St.

Tr. 1270. http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=case&court=us&vol=443&page=368

Jenkins v. McKeithen: 395 U.S. 411 (1969). Due

process right

to a public trial.

http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=case&court=us&vol=395&page=411

Talley v. California:

362 U.S. 60 (1960) re: anonymous pamphlets and press licensing. “John Lilburne was whipped, pilloried and

fined for refusing to answer questions designed to get evidence to

convist him

or someone else for the secret distribution of books in England.” http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=case&court=us&vol=362&page=60

Barenblatt v. United States:

360 U.S.

109 (1959) re: the House Un-American Activities Committee.

“The memory of one of these, John Lilburne –

banished and disgraced by a parliamentary committee on penalty of death

if he

returned to the country – was particularly vivid when our Constitution

was

written. His attack on trials by such

committees and his warning that ‘what is done unto any one may be done

unto

every one’ were part of thehistory of the times.” http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=case&court=us&vol=360&page=109

In

re Oliver: 333 U.S. 257 (1948) “In 1649, a few years after the Long

Parliament abolished the Court of Star Chamber, an accused charged with

high

treason before a Special Commission of Oyer and Terminer claimed the

right to

public trial and apparently was given such a trial. Trial of John Lilburne,

4

How.St.Tr. 1270, 1274.

‘By immemorial usage, wherever the common law prevails, all trials are

in open

court, to which spectators are admitted.’ 2 Bishop, New Criminal

Procedure s

957 (2d Ed.1913).”

http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=case&court=us&vol=333&page=257

Other Readings:

H.N.

Brailsford, The Levellers and

the English Revolution, Spokesman, Nottingham,

1983.

Joseph

Frank, The Levellers; a history of the writings of three

seventeenth-century

social democrats: John Lilburne, Richard Overton and William Walwyn,

Russell & Russell,

New York, 1969.

Samuel

R. Gardiner, The History of

the Great Civil War: 1642–1649, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1891.

Mildred

Ann Gibb, John Lilburne, the Leveller, a Christian

Democrat, L. Drummond, London,

1947.

Pauline

Gregg, Free-born John,

Phoenix Press, London,

2000.

Roderick

Moore, The Levellers: A

Chronology and Bibliography, Study Guide No.4, Libertarian Alliance, London.

A.L.

Morton (editor), Freedom in

Arms: A Selection of Leveller Writings, Lawrence

and Wishart, London, 1975.

Dianne

Purkiss, The English Civil

War: A People's History, Harper Perennial, London, 2007.

Nicholas

Reed, John Lilburne:

Campaigner for Democracy, Lilburne Press, Folkestone, 2004.

Andrew

Sharp ed., The English Levellers, Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge,

1988.

David

Starkey, Monarchy: From the

Middle Ages to Modernity, Harper Press, London, 2006.

A.S.P.

Woodhouse (editor), Puritanism

and Liberty, J. M. Dent and Sons Ltd, London, 1938.

Austin

Woolrych, Britain

in Revolution: 1625–1660, Oxford

University

Press, Oxford,

2002.

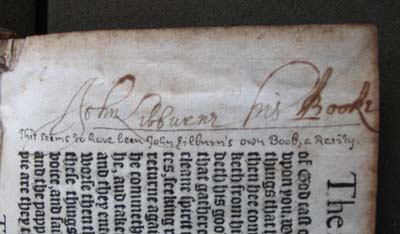

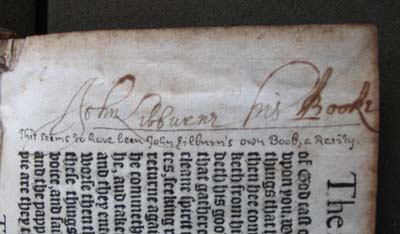

Signature

of John Lilburne: "John

Lilburne his booke" inscribed on a fragment

of printed waste bound as a fly-leaf in a volume of eleven

tracts. These concern the radical Leveller leader's imprisonment,

firstly

in Newgate, and then in the Tower of London,

in 1646 for

producing tracts attacking the House of Lords, one of which, The

freemans

freedome vindicated, appears in this collection.

St. Johns College, University of Cambridge. http://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/library/special_collections/early_books/pix/provenance/lilburne/lilburne.htm

|